Come Writers and Critics

Who Prophesies with your Pen

And keep your eyes wide

The Chance won’t come again

And don’t speak too soon

For the wheel’s still in spin

And there’s no telling’ who

That it’s namin’

For the loser now

Will be later to win

For the times they are a-changin’

- Bob Dylan

Table of Contents

Letter from the Editor

To the Victor Go the Spoils: Democratic Backsliding in Tunisia Since the Arab Spring - Rachel Simroth (Editor-in-Chief)

Do Palestinian Lives Matter? - Michael Sarkis (Managing Editor)

Autonomy Within Marriage - Abriana Malfatti (Managing Editor)

Schild und Schwert der Partei: The East German Secret Police and its Effect on Political Trust - Isabelle Warren

Fraternity, Liberty, Equality: The Hypocrisy of Emmanuel Macron’s Presidency - Macayla Moore

The Role of Food in Culture - Ben Monroe

Meet the Authors

Endnotes

Letter from the Editor

As I reflect on my three years with Alger Magazine, one of the main reasons I kept coming back is its collective nature. The organization brings together undergraduate students who are not only interested in writing and international affairs, but also have a passion for discussing global issues and improving journalist standards. In my sophomore year, I recall a presentation on the tomato shortage in the Souss region in Morocco. In my junior year, another club member led a discussion about music diplomacy in Poland. And in my senior year, we collaborated with BlackXBold magazine on campus by hosting a joint rotating discussion event about current global issues and journalism standards. Thinking critically about global issues and being able to discuss them with people from different backgrounds is incredibly important, and I hope Alger continues to be a space on Ohio State’s campus to do both of those things.

In this Spring 2024 Edition, the articles cover a range of broad and niche topics in international affairs, but going through the submissions, there was a theme that stood out through all of them: Changing Times.Yet this change is not for the better. Rather there are worrisome global trends of diminishing respect for other people, their rights, and their culture. Democratic backsliding and restrictions of freedoms in Tunisia to France have increased in the past five years, and a case study on the use of secret police in East Germany demonstrates how high surveillance and limited freedom negatively affect political trust in society. This edition also calls attention to the high civilian casualty count in Gaza, how women’s bodily autonomy is restricted in the international arena, and the increasing dangers that are represented through the misuse of food culture. Our writers this semester explored these tough and important topics that all highlight worrisome global trends.

Many thanks to the incredible managing editors at Alger Magazine, Abriana Malfatti and Michael Sarkis, for their dedication and hard work throughout this academic year. It has been a pleasure this year to work with you both this past year and bring Alger to new heights. I know I am leaving Alger in good hands with Michael Sarkis taking over as Editor-in-Chief next academic year.

On a personal note, over the past six months, my mind has more frequently dabbled with the idea of becoming an international correspondent, as I think about how I want to connect with and advocate for communities abroad in my career. On that note, last month I read Clarissa Ward’s book On All Fronts: The Education of a Journalist. The autobiography details her career as an international war correspondent around the world, from Syria to Gaza to Afghanistan. Several important themes stood out to me, but there is one in particular I want to share: the dual role journalism has in highlighting the stories of civilians and holding world governments accountable. For Clarissa Ward, that meant all governments. Journalism today must keep asking the hard questions - to hold not only our adversaries accountable, but ourselves and our allies. It takes a great deal of bravery to stand up to our enemies, but often a great deal more to stand up to our friends. And I believe journalists hold an invaluable and important role in holding all of us accountable.

Sincerely,

Rachel Simroth Editor-in-Chief

To the Victor Go the Spoils: Democratic Backsliding in Tunisia Since the Arab Spring

Rachel Simroth

Tunisian democracy has decayed before the eyes of the world. Its initial successful transition from dictatorship to representative democracy in 2011 has experienced significant obstacles over the past decade. Notably, enlarged executive power - at the intentional expense of the legislative and judicial branches - and restrictions on democratic institutions such as civil society and the press have plagued Tunisia. The US must be invested in the successful democratic transition to exhibit that democratic initiatives in the region could work. Already, the rising authoritarianism has prompted a revaluation of US foreign policy towards Tunisia, one where we have limited our foreign aid and are increasingly at odds with European counterparts. Tunisia symbolizes the struggles both emerging and established democracies face amid a global democratic recession, and its upcoming 2024 elections will demonstrate a test for the survival of Tunisian democracy.

The Birth of the Arab Spring

Tunisia’s historic democratic protests over a decade ago generated the progression of a new, optimistic, and young democracy in the Middle East. The uprisings began in Tunisia after street vendor Mohammed Bouazizi infamously set himself on fire outside a municipal office on December 17, 2010, after police repeatedly demanded bribes.2 Unrest quickly spread from the remote central town of Sidi Bouzid to the entire country. Over the next month, police reportedly killed hundreds of individuals who protested against poverty, corruption, and the authoritarian regime of President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali. Yet, President Ben Ali’s promises of reform were not enough to protect his power, and on January 14, 2011, he fled to Saudi Arabia.3 This Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia inspired other revolts against authoritarian leaders - known as the Arab Spring - across the Arab world.4 Yet in the end, Tunisia would be the only country where protests led to a democratic transition, and the work towards establishing a democracy began.

The Hard Realities of a Democratic Transition

Tunisia’s new government signals both successes and failures of a democratic system in the past decade. The country succeeded in forming a liberal constitution and holding free local and national elections. Yet, the Tunisian government has failed to address the root reasons behind the uprisings: rampant corruption, high unemployment, and wide socioeconomic disparities.5 Given this, Tunisia has been plagued by on-and-off protests and increasingly low voter turnouts.

Following President Ben Ali’s departure, an interim government was formed and the former President’s ruling party, the Democratic Constitutional Rally (RCD), was disbanded.6 The national elections in October 2011 witnessed Ennahda - a moderate Islamist party - win and subsequently form a

coalition government with two other secular parties.7 Yet, tension between the religious and secular parties persisted over the next three years. Protests emerged in 2012 against the more conservative religious government and again in 2013 after two prominent secular politicians were assassinated and Ennahda was blamed.8 These tensions would ultimately lead to secular parties beating Islamists in the 2014 elections.9

Tunisia was further destabilized over the next several years as thousands of Tunisians left to join ISIS in the Levant or Libya, terrorist attacks occurred more frequently, and high unemployment and price hikes led to nationwide protests in 2018. Voter turnout reached a record low in the May 2018 elections, and Ennahda “failed to win absolute majorities in many municipalities.”10

The Rise of Kais Saied

Now enter Kais Saied. The sixty-one-year-old law professor at The University of Tunis, with no prior political experience, seemingly overnight rose to win the presidency in October 2019.11 Saied garnered attention due to both his role on the committee of experts drafting the 2014 constitution12 and “often appear[ed] on television stations to explain issues of public interests” as a “constitutional law expert.”13 His refusal to vote in any parliamentary election post- 2011 revolution in protest over the closed-list electoral systems that he believed “disproportionately favored certain parties” positioned him to potentially lead Tunisia towards a more honest democratic systems.14

Presidential elections were called in 2019 after the death of Tunisia’s first democratically elected president, Beji Caid Essebsi. Saied’s presidential campaign did little campaigning and promoted Saied as the “integrity and anti-corruption” candidate.16 Youth voters were particularly drawn to Saied for his anti-corruption reputation.17 His vision for politics threatened the Tunisian political elite and he wanted to decentralize government power. Saied promised election reform, vowed to “fight corruption and promote social justice,” and even viewed healthcare and water as a “part of national security.”18 He even admirably refused to campaign in the weeks leading up to the polls as his rival, Nabil Koroui, was in prison on charges of money laundering and tax fraud.19 In October, Saied won the election with 72.71% of the vote, and around 90% of 18-to-25 year-olds voted for Saied, according to the Sigma polling institute.20

The Beginning of the End: The July 2021 Coup

Yet the renewed optimism about improving Tunisian democracy, generated by the promises of a new-Saied era government, would be crushed within two years. On July 25, 2021, Saied issued an emergency declaration that suspended parliament for thirty days, fired the Prime Minister, and he assumed all executive power. The day after, he codified his actions in a presidential decree, justified by Article 80 of the 2014 Tunisian Constitution as a means to preserve the security of Tunisia21:

Article 80 of the 2014 Tunisian Constitution: “In the event of imminent danger threatening the nation’s institutions or the security or independence of the country, and hampering the normal functioning of the state, the President of the Republic may take any measures necessitated by the exceptional circumstances,afterconsultationwiththeHeadofGovernmentandthe Speaker of the Assembly of the Representatives of the People [Par- liament] and informing the President of the Constitutional Court.”22

Changes to Tunisian Society Post-2021 Coup

Expansion of executive power

Over the past three years, Tunisia has been plagued by fattening executive power as Saied eliminates crucial democratic checks and balances on his presidency. Saied initially in September 2021 transferred the powers of parliament to himself, and then ultimately in March 2022 completely dissolved parliament.24 Saied accused parliament of a failed coup and ordered investigations against them.25 The dissolvement of the democratically elected parliamentin Tunisia was the biggest challenge to its governmental system since the 2011 revolution as a crucial legislative check on executive power was removed.

Throughout 2022, Saied issued several presidential decrees intended to weaken the role of political parties and imposed strict requirements to run for Parliament. Saied repeatedly targeted his political opponents, as he perceives political opposition figures to be his enemies, vowing to fight a “relentless war” against them, and has jailed Ennahda party leader Ghannouchi and detained the president of the National Salvation Front coalition Chebbi.26

Reduction in judicial power

Saied’s demonization of perceived threats to his power is displayed through his elimination of the independent judiciary system. He dissolved the Supreme Judicial Council on February 6, 2022, because it served political interests and “positions and appointments are sold and made according to affiliation.”27 This important notion of separation of powers was further eroded when Saied issued a decree empowering the president to fire judges,28 and he began enacting that power in June of that same year when he fired fifty-seven judges on shaky corruption charges and accused them of protecting terrorists.29

Attacks on civil society

Tunisian civil society has been targeted by Saied’s growing authoritarianism. Yet, the lack of Western attention and inital consequences of his coup, and subsequent censorship attacks, indicated to Saied that he had the runway to test his new authoritarianism. A massive political crackdown in February 2023 saw journalists and business leaders arrested for plotting against the state, and Ennahda offices – the main opposition political party in Tunisia – were forcibly closed in February 2023.30

President Saied’s government targets journalists critical of his coup and policies, repeatedly undermines freedom of the press, and imposes vague prison sentences for “false information or rumors.’’32 Mohammed Boughaleb - a prominent Tunisian journalist who works with local independent media network Carthage Plus and radio station Cap FM -

was detained by Tunisian authorities on March 22, 2024. He was charged with “defaming others on social media’’ and “attributing false news to a state official without proof ” after an employee at the Ministry of Religious Affairs filed a defamation complaint against him for statements Boughlabed made on radio and TV about ministry policies.33 According to the International Federation of Journalists, more than thirty journalists were arrested in Tunisia in 2023.34

One of the most troubling government actions against civil society is a current draft law attempting to restrict NGOs that receive foreign financing. Introduced in November 2023, the law would replace Decree-Law 2011-88 on associations, which has become a critical ingredient in fostering a robust and diverse civil society in Tunisia post-Jasmine Revolution. According to Human Rights Watch, this law would “grant the government persuasive control and oversight over the establishment, activities, operations, and funding of independent groups.” The law would introduce a registration system that gives the Prime Minister’s Office the authority to deny a group the right to operate, without requiring a reason to be given. Additionally, registration of foreign organizations would be at the whims of approval at

the total discretion of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, without the right to an appeal.35 This law is one of the last surviving counterweights to Saied’s autocracy, and if passed, the law could have devastating impacts on all partners that work with foreign NGOs.

Lack of trust in elections

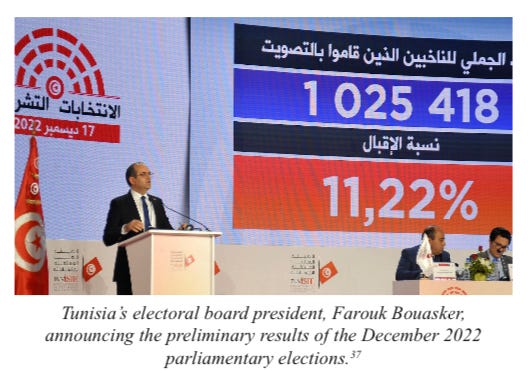

Democratic backsliding in Tunisia has fueled troubling disillusionment with democratic processes, reflected in significantly low voter turnout in elections. Only 11.2% of Tunisians participated in the December 2022 elections to replace the Parliament Saied disbanded, and 11.3 % participated in the parliamentary runoffs the following month. With governments continuing to censor public discourse and rig elections, the opposition movements often boycott them to protest these manipulated democratic systems.36

Rejection of foreign assistance

President Saied’s rhetoric increasingly rejects crucial foreign assistance as a means to protest Western nations that commonly provide it. President Saied rejected an IMF loan to Tunisia conditioned on democratic reforms, condemning them as “foreign diktats.”38 He publicly dismisses European

assistance as handouts that are beneath his country and vehemently rejects “foreign interference” after the United States more publicly raised concerns over the arrests of his critics.39 Saied’s rampant nationalism and resistance to Western influence dictate his rejection

of the terms of the proposed International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan to help meet scheduled debt payments.40 His staunch anti-West position allows him to maintain his popularity and credibility with the Arab street, as Saied’s denunciation of the West continues to be an effective method to protect his power.

Evolution of US Foreign Policy Towards Tunisia

US Executive Branch Engagement with Tunisia Pre and Post-Coup

Immediately following the successful democratic transition post-Arab Spring, the executive branch of the US was actively engaged in Tunisia. Between 2010- 2015, the US Secretary of State made four visits to Tunisia, and top US officials gave dozens of speeches about the country, including a mention in one of Obama’s State of Union addresses.41 These high-profile engagements reflect intensive diplomatic engagements across the US government towards Tunisia and our values to uplift emerging democratic societies. Yet by 2015, the US took a backseat to engaging with Tunisia, as attention shifted elsewhere in the region, such as toward Syria, Libya, and the rise of ISIS.

After the July 2021 coup, the White House initially expressed only “concern” and “urge[d] calm” in Tunisia.42 Similarly, in February 2022, after Saied dissolved the Supreme Judicial Council, the State Department spokesperson Ned Price stated the “United States is deeply concerned” - yet US policy towards Tunisia remained unchanged.43

Congressional Action

Conversely, Congress has repeatedly pressured Tunisia to return to democracy. According to a Senate aide, there was increased pressure from the four corner Committees (both Republicans and Democrats on the House and Senate Foreign Affairs Committees) on Tunisia after Saied suspended parliament. Specifically, there were a couple of four-corner letters to the Administration and the President of Tunisia expressing Congressional concern over Tunisia’s democratic backsliding. Yet, the aide said the repeated use of public and private congressional channels to warn Tunisia “that the path they were on was going to jeopardize the bilateral relationship was ignored by the Tunisians” and therefore, “the process of legislation became necessary.”44

In June 2023, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee introduced the Safeguarding Tunisian Democracy Act to “foster Tunisia’s democratic institutions, limit funds until Tunisia restores checks and balances, and authorize the creation of a fund to support democratic reforms.’’45 The bill limits State Department funding to Tunisia by 25% — including security assistance — until the following benchmarks are met: end military courts to try civilians, make clear and consistent progress to releasing political prisoners, and terminate all states of emergency. The 25% cut was intentionally placed across several accounts — not just foreign military financing — as Congress did not want to entirely withdraw counterterrorism assistance with the Tunisian military. The US has “worked for many years to make them an apolitical actor” and “we have no interest in the Tunisian military getting even more involved in politics” a Senate aide explained.46

One crucial section of the Safeguarding Tunisian Democracy Act was the exception of civil society from the funding cut. This piece was incredibly important when negotiating the language of this legislation, a Senate aide explained, as without that “expectation in the bill, we would not have support from most of the Democratic members on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.”47 Protecting civil society in Tunisia is important to US foreign policy interests and values for several reasons:

“For a decade, the United States invested in Tunisian civil society, in NGOs, in women’s empowerment, and tried to create the substratum that helps make democracy sustainable in the long run. You can have elections, you can have parliaments, but if you don’t have a committed civil society cohort that cares about participatory democracy, then you’re building on a weak foundation. And so Congress did not want our legislation to be directed at the people who are being targeted by the repression of the government of Tunisian” a Senate aide outlined.48

The Act also includes the creation of a ‘Tunisia Democracy Support Fund’ which authorizes the appropriation of $100 million in both 2024 and 202 for the State Department to utilize to support democratic nstitutions. However, this money only becomes available if Tunisia meets the outline benchmarks towards restoring democracy.49 The inclusion of these funds satisfied both a policy and political objective, a Senate aide explained. The policy objective “was to support actual reforms that we wanted to see happen on both the democracy and economic side,” and the political objective was to not provide Saied fuel for his nationalistic rhetoric by characterizing the US as “not serious about helping Tunisia and they just want to bully us into doing what they want us to do.”50

Disagreements over Policy Between US and European Counterparts

However, there continues to be a multidimensional tension between Congress, the Administration, and the Europeans on how to deal with this democratic backsliding in Tunisia. Opposition from select voices in the executive branch to Congress’ approach is coming from those who “care a lot about the security relationship with the Tunisian military,” a Senate aide outlined. However, over time there appears to have been “an evolution in thinking about who Kais Saied is and what his intentions are” within the broader US government, and the initial assumption he would be flexible has diminished. As it stands now, the US foreign policy towards Tunisia is a multi-avenue diplomatic approach between Congress and the State Department to incentivize Saied to implement economic reforms and meet the outlined democratic benchmarks. The current approach allows “the [US] embassy [to] use Congress as the bad cop” when negotiating with the Tunisian government, as an intentional effort to “give a little bit of wind in the sails of our Ambassador to Tunis,” a Senate aide explained.51

Yet, the United States and Europe do not have a united front in our policy approach to protecting Tunisian democracy. Europeans’ concerns around Tunisia concentrate on increased migration into Europe, rather than solving the repression of democratic norms and faulty economy that motivates the migration. In September 2023, the European Commission awarded 127 million euros ($133 million) in aid to Tunisia to fight illegal immigration.52 Not all Europeans are on the same page, however, as countries that border the Mediterranean Sea and are the high entry point for Tunisian migrants - most notably Italy - have the most far-right approach. For example, the “Italian Prime Minister with the European Commissioner’s blessing has negotiated, behind the backs of the German government and everyone else, to give money to the Tunisians,” a Senate aide articulated.53 The rift between the US and European policy approach to Tunisia is drifting further apart as certain European governments continue to form stronger anti- migration partnerships with President Saied’s increasingly authoritarian regime, rather than adjusting foreign aid levels to encourage him to implement democratic reforms.

The Upcoming 2024 Elections

The fall 2024 presidential elections will be a significant test for this weakened state of democracy in Tunisia. Even though Saied has not officially announced his plans to run for a second term, both leaders of the Islamist party Ennahda and the right-wing Free Destourian Party are imprisoned.54 “The opposition does not have its act together,” a Senate aide evaluates, as “there is not a unified opposition candidate” against Saied. His nationalist and populist rhetoric still “makes him the most popular politician in Tunisia,” as his posture against the West — only further emboldened by the current Gaza conflict — “plays into the Arab street populism” the Senate aide further explained.55

These upcoming elections in Tunisia are one of many tests for democracy around the world this year. The Tunisia case will demonstrate regional significance, as Tunisia had become the primary example of democratic progress in North Africa post-Arab Spring, where autocrats and strongman rule have been the norm. Attempts to restore democracy and growing economic hardships will be at the center of the election, with unemployment at 15% and inflation at 10%, food prices spiking, and increased migration.56 Saied’s assault on hard-earned democratic institutions over the past three years will likely produce an election process that is not free or fair. Tunisia’s democracy remains a work in progress, yet it is the values and interests of citizens globally that in the end, the victors are ordinary Tunisians, not Kais Saied.

Do Palestinian Lives Matter?

Michael Sarkis

“We are fighting human animals, and we will act accordingly.”1 On October 9, 2023, Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant used these words to describe the two million Palestinian inhabitants of Gaza. His comments followed the announcement of a complete siege on the Gaza Strip, prohibiting the entrance of food, fuel, and electricity, as Israel was planning its invasion of the Gaza Strip following the Hamas attack on October 7, 2023.

Defense Minister Gallant is not the only Israeli official to have previously used dehumanizing language to describe Palestinians following the October 7th attack. In the same month, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu encouraged Israelis to “remember what Amalek has done to you.”2 With this comment, Prime Minister Netanyahu was referring to the story of God “commanding” King Saul to exterminate every single Amalekite to retaliate for their attack on Israel.

Israel’s conduct over the past six months in the current Gaza War reflects its leaders’ violent rhetoric. Within the first twenty-five days of Israel’s invasion of the Gaza Strip, more than 3,600 Palestinian children were killed.4 More children have died in the first three weeks of the Gaza war than in all world conflicts combined in the last three years.5

Similarly, Israel has targeted areas it first designated as safe for civilians. In the early weeks of the Gaza War, Israel ordered the residents of Northern Gaza to evacuate and relocate to southern Gaza.6 A New York Times investigation found that Israel used 2,000 pound bombs in areas it had deemed safe for citizens fleeing from northern Gaza.7 These bombs create craters 40 feet or longer. Examining drone visual footage and satellite imagery, the New York Times has counted at least 208 craters in southern Gaza.8

The bloodshed and devastation only increased since the beginning of the Gaza War. In February 2024, Palestinians in Gaza City had congregated on Al- Rashid Street to receive flour from aid trucks they were expecting.9 They confronted gun fire from the Israeli Defense Forces. The Gaza Ministry of Health reported at least 112 Palestinians killed and more than 750 wounded.10 Israel disputed this account, with the spokesperson for the Israeli Defense Forces claiming “No IDF strike was conducted towards the aid convoy “and rather the tanks had fired warning shots to disperse the crowd and ultimately “dozens had been trampled to death or injured in a fight to take supplies off the truck.” 11 Despite Israel’s denial of culpability, its actions are condemned by an increasing number of nations, including the United Nations and the International Court of Justice. The White House labeled it as a “tragic and alarming incident” and has demanded a probe into the situation.12

My title asks, “Do Palestinian Lives Matter?” In the context of Israeli actions outlined above, my answer is clearly no. The rhetoric of Israeli leaders and Israel’s military strategy demonstrates flagrant disregard for the lives and livelihoods of innocent Palestinian citizens. The atrocities committed by the Israeli military mentioned above only scratch the surface of the devastation that Israel continues against the Gaza Strip and its people. What explains Israel’s callousness towards Palestinian life? What theoretical framework illuminates our understanding of Israeli policy and actions toward the Palestinian people? My answer lies in necropolitics.

In his groundbreaking article “Necropolitics,” Achille Mbembe defines the theory as “the subjugation of life to the power of death.”13 Mbembe employs necropolitcs to explain how “weapons are deployed in the interest of maximum destruction of persons and the creation of death-worlds, new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to conditions of life conferring upon them the status of living dead.”14 Three main factors constitute “death- worlds.” They are: 1) confining certain populations to certain spaces, 2) producing death on a substantial scale, and 3) creating a necroeconomy which seeks to manage excess populations by exposing them to life-threatening situations.15

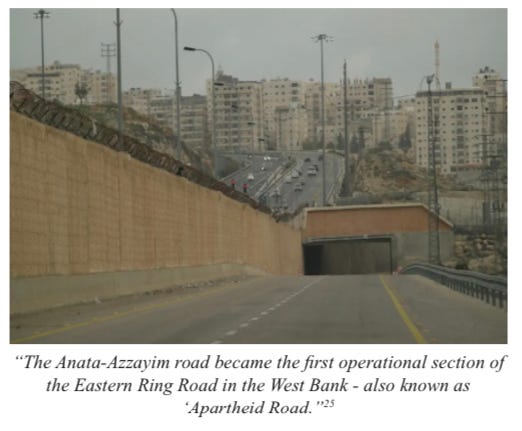

Writing in 2005, Mbembe identified Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip as a site of necropower. He characterizes that through three features: territorial fragmentation, “vertical sovereignty,” and infrastructural warfare.16By territorial fragmentation, Mbembe refers to the expansion and sealing off of Israeli settlements.17 He argues that the purpose of Israel’s settlement project is “to render any movement impossible and to implement separation along the model of the apartheid state.”18 The settlement project achieves this goal by partitioning the Occupied Palestinian Territories into “a web of intricate internal borders and various isolated cells.”19Borrowing from the work of Eyal Weizzman on “the politics of verticality,” Mbembe next introduces the concept of vertical sovereignty. This entails a colonial power operating “through schemes of over- and underpasses, a separation of the airspace from the ground.”20 Israel enacts its vertical sovereignty over the West Bank by dividing the territory by creating multiple provisional boundaries and separations that interrelate with each other through surveillance and control. This results in a splintering occupation, illustrated by two examples.21 The Oslo Accords divided the West Bank into three sectors. While Israel exerts military and civil control over 60% of the West Bank (Area C), Palestinians civilly and militarily control only 18% of the West Bank (Area A),exerting only civilian control in the remaining 22% (Area B).22 Area A and B are further fragmented into 166 enclaves, while Area C is a continuous territory.23 Another example is the roads separating Israeli settlers from Palestinians. Weizmann argues that the West Bank’s bypass roads aim to separate Israeli and Palestinian traffic from each other. When they cross paths, Palestinians are forced to use small roads dug under the highways connecting the settlements, which only Israeli personnel may use.24

Similarly, Mbembe identifies the airspace as an important site for occupation because the majority of surveillance is conducted from the air.26 One result of the occupation of air spaces is allowance for precise killing. This combines with “the tactics of medieval siege warfare” to disrupt and undermine Palestinian urban and societal infrastructure.27 Specifically, Israel disrupts Palestinian infrastructure through infrastructural warfare.28 Mbembe argues points to bulldozing as a key feature of Israel’s infrastructural warfare against Palestinians. Bulldozing encompasses more than the demolition of houses and cities. It includes the:

uprooting olive trees; riddling water tanks with bullets; bombing and jamming electronic communications; digging up roads; destroying electricity transformers; tearing up airport runways; disabling tele- vision and radio transmitters; smashing computers; ran- sacking cultural and politico-bureaucratic symbols of the proto-Palestinian state; looting medical equipment.”29

Much has changed since Mbembe wrote “Necropolitics” in 2005. Since publication, Israel first disengaged from the Gaza Strip in 2005, uprooting more than 9000 Israeli settlers in order to boost Israeli security.31 Following Israeli disengagement, Hamas won the 2006 Palestinian elections.32 Despite its victory, Fatah ousted Hamas from power in the West Bank.33 In response, Hamas seized control of the Gaza Strip, creating a schism between it and the Fatah-run West Bank.34 Viewing this as an unfavorable development, Israel imposed a land, air, and sea blockade of the Gaza Strip with assistance from the Egyptian government in 2007.35 Israel’s blockade contributes to the Gaza Strip’s weak economy, with more than 53% of Gazan residents living under the poverty line in 2020.36 The blockade hinders access to food within Gaza, resulting in at least 64% of Gazans experiencing food insecurity in 2022 before the current conflict.37 This blockade turned Gaza into an open-air prison, according to Omar Shakir of Human Rights Watch.38

In 2016, Mbembe expanded upon his idea of necropolitics in his book: Necropolitics. In discussing the Israeli occupation of Palestine, Mbembe mostly repeats his earlier views, but he does provide new analysis. He argues that the Israeli government a ttempts to implement a policy of separation between Israeli and Palestinian society. Israel achieves its regime of separation by pursuing a wide variety of policies including but not limited to targeted assassinations, checkpoints, military incursions, the uprooting of olive groves, and the desecration of Palestinian cemeteries.39

Similarly, Mbembe identifies the occupation of the Palestinian territories as a “laboratory” or workshop to test “a number of techniques of control, surveillance, and separation that are today proliferating in other places on the planet.”40 He points to imposing curfews on Palestinian regions, control of Palestinian movement in the Occupied Territories, regulating the number of Palestinians allowed into Israel, and more.41

Between the publication of Mbembe’s article and book, and today, I believe Israeli government policy continues to enact a program of necropolitics on the Palestinian people. As of this writing, Israel has no apparent intention of changing course. In February 2024, Prime Minister Netanyahu presented a post-war plan for the Gaza Strip to his cabinet,42 that envisions a demilitarized Gaza Strip with a security perimeter indefinitely controlled by Israel.43 Beyond a security perimeter, the plan proposes a “southern lock” on the Gaza-Egyptian border in order to prevent the rearmament of certain Palestinian groups.44

As to who will control the Gaza Strip, the Prime Minister does not mention the Palestinian Authority. Instead, he proposes that the Strip be administered by local Palestinians who are not affiliated with any state or group “supporting terrorism.”46 If enacted, this plan will continue the fragmentation of Palestinian land and further Israeli dominance of Palestinian civil society. It will only perpetuate the subjugation of Palestinian “life to death.”

Autonomy within Marriage

Abriana Malfatti

International Law makes it clear that people have individual rights. This can be seen in the first sentence of the Preamble for the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) which shows that the world recognizes “the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.”2 Plenty of international law has developed since the UDHR’s conception in 1948. Treaties are ratified and our rights as humans seem to keep growing. Despite the fact that international law appears to be moving in a positive direction, fundamental rights around the world are still being violated. One of these violations is the loss of bodily autonomy within the marriage. In simplest terms bodily autonomy can be described as, “my body is for me; my body is my own. It’s about power, and it’s about agency. It’s about choice, and it’s about dignity.”3 When states allow spouses to be raped by their partner with no legal consequences, they are saying that marriage is an exception to violate ones own bodily autonomy. The implication is that by saying “I Do” we give up our own personal freedoms. International law disagrees with this sentiment. Though there is significant debate on the practicality of enforcing international law on the state level, this argument will take a liberalist perspective saying that there is value in upholding international law and that international law is designed to uphold one’s individual rights. It is the goal of international law to sustain an individual’s right to bodily autonomy, and international law should focus on promoting rights of the individuals over prioritizing the state. This article will examine what international law says about marital rape and look at two examples of how international law is being violated at the state level. It will then offer up final conclusions about the purpose of the law in protecting our own autonomy while in marriage.

Rights in the marriage; autonomy and marital rape

The first mention of rape can be seen in the Geneva Conventions where rape is condemed and defined as an explicit violation of human rights.4 The act of rape was seen as a direct result of state conflicts during the time and would eventually be considered an act of torture. While the first Geneva Convention did not explicitly state and define the term rape, it did prohibit “violence to life and person” and any form of torture that “outrages upon personal dignity.”5 It was not until Article Four of the Geneva Convention, specifically Protocol Two that makes mention of the term rape. Article Four concludes that rape is a human rights violation that can be prosecuted in criminal court. International law moved even further in protecting ones autonomy from sexual violence in two key cases that define rape as a war crime punishable under international law. In both the Takashi Sakai case and the John Schultz case, military tribunals in both China and the United States concluded that,“(rape is a) crime universally recognized as properly punishable under the law of war.”6 While this may have acknowledged the problem of sexual violence in times of conflict, it fails to dive deep into the problem of rape within relationships, especially mairrage.When these laws were formulated, second wave feminism had not begun. Rape, was primarily seen

as a womens’ issue.

The first mention of marital rape in international law is in the UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women (VAW) in 1993. Article 1 of VAW gives us an idea on why marital rape, or any violence for that matter is a violation of one’s bodily autonomy. According to VAW, sexual violence can be described as“ any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.”7 It is the use of the wording “arbitrary deprivation of liberty” that shows that this is an issue of bodily autonomy. To have bodily autonomy, one should be allowed to make their own choices in life, and to be deprived of “liberty” is to be deprived of autonomy. In addition to this interpretation, VAW goes even further in proving that marital rape is a violation of ones autonomy. In Article 2.a of VAW adds that, “marital rape” is specifically listed as a violation.8 Then, Article 3 of VAW goes even further by adding that women have the right to “liberty and security of person” and the right to “the highest standard of physical and mental health”.9 If all of the above holds true, then their can be no doubt that not only rape, but also marital rape is a violation of human rights and a violation of ones own autonomy.

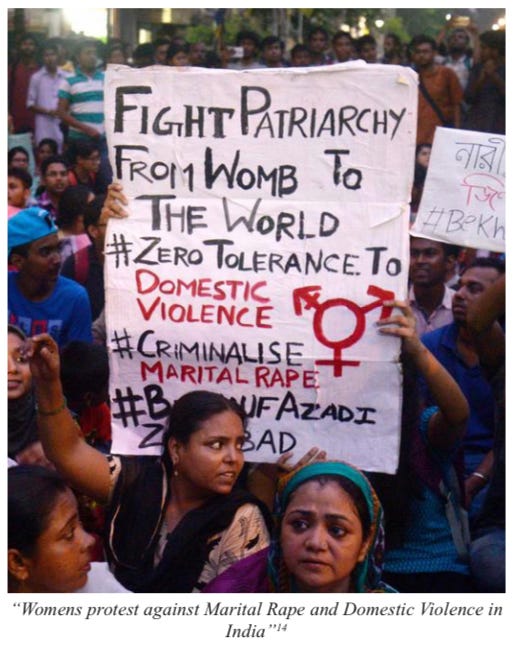

Despite the fact that marital rape is considered a violation of our own autonomy, it is not universally criminalized. According to the World Bank, 112 countries do not criminalize marital rape.11 In addition to these violations, 20 countries have what is known as “marry your rapist laws.” These laws allow a rapist to escape criminal prosecution if they marry their rape victims. According to Dima Dabbous, director of Equality Now’s Middle East and Africa regions, these laws reflect a culture “that does not think women should have bodily autonomy and that they are the property of the family. It’s a tribal and antiquated approach to sexuality and honor mixed together.”12 It is not only in countries with marry your rapist laws that women are trapped and deprived of their own autonomy. According to a report done by the UNFP, “nearly half of women (45%) in 57 countries are denied the right to say no to sex with their partner, use contraception, or seek health care.”13 International law implies the women are in charge of their own bodies, yet many women are forced into acts of sexual violence in their daily lives. It becomes hard to argue that states know our rights better than ourselves when they silence half of their population and deprive them of their right to say no.

Despite state oppression, people - especially women - continue to fight for the right to be in control of their own bodies. In India, pressure is being put on the government to criminalize marital rape. The Domestic Violence Act (PWDV) allowed for civil remedies for marital rape in India, yet marital rape is not a criminal offense and has no criminal repercussions. According to section 375 of the Indian Penal Code, “sexual intercorse or sexual acts by a man with his own wife... is not rape”15 In addition to this if a man rapes a spouse that he is separated from, Penal Code 375 B makes it so that the charges against him are lesser than they would be if he was not a former spouse.16 These laws allow for sexual violence within the marriage to continue without retribution. According to the National Family Health Survey, “Among married women 18-44 (in India) who have ever experiencedmsexual violence, 83 percent report their current husband and 13 percent report a former husband asa perpetrator.”17 The issue of marital rape is damaging to a multitude of women throughout India. In 2022, India nearly achieved a legal victory that would have declared marital rape unconstitutional. In RIT foundation v Union of India, a two person court issued a split decison on whether the rape exemption for spouses was unconstitutional. The judges’ disagreement capture the two sides dividing nations who allow marital rape. Justice Hari Shankar issued an opinion against overruling the marital rape exception. He argued that the rule would be all encompassing and jeopardize the privacy and sanctity of marriage. His argument is in favor of many traditional arguments that claim that privacy in the household is more important than a woman’s right to bodily autonomy. Justice Rajiv Shakdher offers a more hopeful interpretation of the constitution that means there may yet be hope for eventually criminalizing marital rape in the future for India. Shakdher’s opinion matches international law’s interpretation of bodily autonomy as a fundamental right for everyone, not solely belonging to one gender. In Shakdher’s opinion, they write, “denial of bodily autonomy and agency of married women, which must be rectified...suffers from manifest arbitrariness and discrimination as a crime as heinous as rape is not recognized as an offense in marriage.”18 In their opinion they mention both “arbitrariness and discrimination” this is inline with the rights of women outlined all throughout VAW. A possible interpretation of this opinion can be that oppressive states may begin to start moving more in favor of respecting rights outlined in international treaties despite their rigid past.

Final Thoughts

A basic reading of international law makes it clear that our rights to our bodies and our rights to makeour own decisions do not end when we enter into marriage. By allowing exceptions to international law when it comes to marriage, states deprive their citizens of their basic dignity. While rights within marriage seem oppressive over the years, a new wave does seem to be turning. The United Nations seems to finally be prioritizing issues that effect gender and have to do with sexual violence. The only way to gain our freedom back is to keep fighting. The reason laws have changed and why women have gained more rights through various laws over the years is because we refused to have our voices silenced. We should all take inspiration from the courageous women of India who know their own worth and never stop fighting for it. Even if this issue may not seem to affect some people we should also never stop fighting to advance the rights of others. Immanuel Kant described it best when introducing his categorical imperative.19 To build the world we want to live in it requires us to act how we want those around us to act. In simpler terms it is not good enough to just acknowledge that international law is being violated, we should use our voices as well to stop the injustice. If an individual values the right to their own autonomy then they would use the law to protect others’ right to their own autonomy as well.

Schild und Schwert der Partei: The East German Secret Police and its Effect on Political Trust

Isabelle Warren

“Die bisher dem Ministerium des Innern unterstellte Hauptverwaltung zum Schutze der Volkswirtschaft wird zu einem selbstständigen Ministerium für Staatssicherheit umgebildet.”

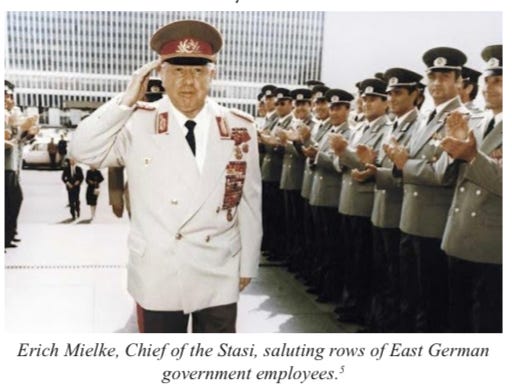

With this declaration, the German Democratic Republic’s (GDR) Volkskammer created the Ministerium für Staatsicherheit, known as the Stasi, on February 8th, 1950, that would become the secret police force and physical power behind the ruling Communist Party.1 The actions of the Stasi were a point of pride for the long-term Chief Erich Mielke, who maintained that they were the “Schild und Schwert,” or Sword and Shield, protecting the ideals and decisions of the East German regime (the SED) against both inside dissent and outside penetration.2 In reality, the Stasi created an environment where no one could escape the scrutiny of the government due to the vast size of the police force and informant numbers. At the end of

the East German regime, there was approximately

one informant for every 80-160 citizens depending on geographical district.3 How could one feel safe or trust their government in a society with the highest surveillance rate in history?4

The scope and range of the Stasi’s focus partially made them daunting for East German citizens. At least six departments and over 200 district administrations monitored the East German army, the police forces, dissident and church groups, postal and telephone surveillance, and economic plans.6 In the beginning, the Stasi’s efforts were focused on individuals who openly opposed the SED, especially groups established by the West German Christian Democratic Union.7 The Stasi maintained a full “prison system, guards unit, academy, medical service, bank branch, and professional sports league.”8 The secret police was a large enterprise that increasingly hired more indiviudals, which added to the fear surrounding them. After the first decade of existence, there were 20,000 ministry employees, then in the second decade there were 45,500 employees. By 1982, the end of the third decade, the Stasi employed 81,500 individuals.9 For an organization with interests in different societal factions, they also had an extreme reach within dissident communities and were legally allowed to “carry out house searches, install bugging systems, confiscate illegal literature, and prevent planned events.”10 The Stasi attempted to infiltrate every organization they could in their mission to defend the East German government.

The number of informants employed by the Stasi created a culture of fear in the lives of citizens and yielded an extremely large amount of information collected. When hiring new informants, referred to as Inoffizielle Mitarbeiter or IMs, the Stasi accepted information from anyone who was not connected to West Germany, and only a small number of political dissidents.11 These IMs were the “main strength of the MfS for penetrating the conspiracy of the enemy.”12 The goal was to promote the Communist Party and dispel any and all disagreement. In furthering this goal, the Stasi had the lowest rate of workers with an Abitur, the German equivalent of a high school diploma that allows them to go to university. In limiting the number of people able to think and analyze, they limited the number of employees who could think critically about their actions and the validity of their mission in society.13 It was easy to push the limits of societal relationships and trust if you could not think critically about whether your actions were effective. Additionally, over 50% of Stasi employees were recruited from families where one or both parents worked for the government or the ruling party. This insulated the Stasi from other viewpoints and increased their conviction and confidence in the SED.14Despite this, some of the Stasi remained well aware of the social situation in East Germany and the amount of dissent present in the country.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the Stasi informant culture is the motivations of people who spied on their coworkers, friends, and family. This is the most difficult thing to conceptualize for those outside of the system. Some informants genuinely thought they were doing good for their country and became informants out of conviction. They wanted to support their government and eliminate any dissent. For some, it was less about moral conviction and more about earning extra money to support themselves or guaranteeing their ability to succeed in their career fields by cooperating with the government. It was a part of life for some people, but this was not the case for everyone. The Stasi had information on people who were struggling and leveraged their misfortune to gain information. They would promise silence in exchange for becoming an informant, which put many East Germans in difficult situations.15 Not all informants were active for the longevity of the Stasi, but the public perception was that spies and informants were everywhere. This was just as effective at changing behavior as actually having a spy because everyone was under the impression they were being monitored.

When the SED collapsed, the Stasi collapsed alongside it. It became incredibly important to determine what should be done with all of the collected information. There were 178 kilometers of archival materials, six million personal files, 40 million index cards, one million pictures and negatives, and thousands of human scents stored in jars.16 Over four million East German citizens and two million foreign nationals were monitored by the Stasi at some point.17 From the beginning, some party loyalists were trying to destroy the files that were eventually recovered in an ongoing project by the Stasi Records Archive. This prompted the invasion of Stasi headquarters in Berlin in January 1990 to prevent further destruction.18 German citizens were not only facing changes to their lifestyle caused by the reunification of Germany but also the fallout of extensive spying on their political trust. The new Federal Republic of Germany passed the “Stasi Document Law” in November 1991, which “established a precedent of privileging the right to informational self-determination over the right to privacy of former officials of dictatorial secret police agencies” and created the Office of the Federal Commissioner for the Files of the State Security Service of the former German Democratic Republic.20 This allows citizens to access their Stasi files and see who reported on their activities. The law also limited former Stasi collaboratives from holding prominent positions in the new government, which more or less ruined their futures. This revelation seems enough to question whether governments or even people close to you are to be trusted.

The fallout of the Stasi activity seems to have motivated former East German citizens to prevent a similar thing from ever happening again. In

particular, former Chancellor Angela Merkel was very open about how her experience in the GDR motivated her to campaign for political and economic freedom for Germans. When the NSA spying case was brought to light, she was incredibly critical of the U.S. government and the NSA because of her personal experience with Stasi interference.21 One thing the government did correctly was allow people to view their own files, emphasizing the right to privacy for ordinary people.22 This allowed for a sense of trust

to be restored. This process was not secret, and the commission spread the paperwork to access individual files as far as possible. This could be why Germany has found success in transitioning into a post-Communist nation, compared to other post-Communist countries.

Trust in the Soviet Union was used as a tool to insulate the country under Stalin’s rule and break down potential opposition. The Communist Party intensified its rhetoric throughout the 1920s and 1930s emphasizing the division between the USSR and other countries, especially through the popularization of the phrase, “He who is not with us is against us.”23 The political elites and academics were distrustful of each other because they could easily have been accused of opposing the leadership. Even workplaces were riddled with mistrust as employees were encouraged to “unmask enemies” in their colleagues and superiors.24 These grievances ranged from “social origin, ideological errors, apparent responsibility for a work accident, previous concealed political activity, a connection to someone previously convicted or living abroad” and no evidence of these claims was necessary.25 To deal with the pervasive mistrust and constant informing, people formed groups called “mutual protection associations” in which they agreed to not inform on each other, developing a distinct sense of trust within these groups.26 In the decade of living under Stalin’s Terror, it became necessary to form these groups because most citizens had no one to rely on and felt they could not even trust the government, which faced personnel changes because of mistrust within the ruling party.

Beyond outright mistrust of each other, the fear of the Soviet Committee for State Security, known as the KGB, and spying was prevalent in the USSR as it was in the DDR. The Soviet rhetoric of comrades versus enemies took a real structure in KGB spying on dissidents. They were referred to as ideological saboteurs and a specific directorate was written to combat what they viewed as Western powers infiltrating the Soviet Union. To combat these dissidents, the KGB planted informers within different circles to target dissidents and those smuggling literary texts to other countries.27 The KGB files at the collapse of the Soviet Union were transferred to the repositories of the Russian Federation and separated into the appropriate ministries.28 Many people wanted to see the contents of the domestic security files because of their ability to exonerate the alleged four million cases of dissident crimes that were prosecuted in the USSR.29 However, the Yeltsin government did not make it a priority to make these files public for Russians. This could have changed Russia’s trajectory after the collapse of the Soviet Union towards democracy. If the government had chosen transparency like the newly forming German government in 1991, then the new government may not have held the same power over its citizens that the Soviet Union regime did. It is also likely that this secrecy led to more deeply ingrained mistrust in the Russian government, continuing the oppressive nature of the government.

For post-communist countries, like Romania, the transition to democracy was incredibly difficult in contrast to Germany because there was no trust in the government or political institutions. Romanian security files were used to target the relationships formed between people and the trust in society similar to the Soviet Union.31 The communist regime targeted any dissident or individual as an enemy and created “dossiers of informative pursual” (DIPs) that could include anything from interrogation notes to surveillance data.32 At the end of the Communist regime, the Romanian Intelligence Service had amassed approximately 100 million individual files.33 Similar to East Germany, some of these files were destroyed in the beginning but not all preserved files have been open to the public. Romania did pass two legal measures to ensure the free access of the DIPs to those affected, but some are still protected in the archives of the new Romanian Intelligence Services (SRI).34 While the Romanian government did not take the exact same steps toward opening up security files to the public, they were able to transition to democracy over time. Romania very quickly established an electoral democracy and granted freedom to the press and freedom of association within days of the regime change.35 Their series of successful elections leading into the 2000s and the introduction of a new constitution led to Romania’s invitation to join the European Union, cementing its place as a successful democratic nation.36 Additionally, opening access to the files allowed affected Romanians to reconstruct their family’s past and bridge the gap between generations. They inspired a new genre of biography that focuses on the truth of years under communism.37 Recreating these familial stories and understanding the gaps in history created a new bond in society, which likely erased much of the mistrust in the government and eased the transition to democracy.

While East Germany was not home to the only secret police under communism, the Ministry for State Security created an intense culture of fear and mistrust in the country. Despite this, the Federal Republic of Germany’s decision to open the secret police files facilitated a quick transition to democracy that likely would not have occurred if another decision had been made. The case of East Germany can serve as a lesson for future nations transitioning from communism to democracy to gain back the trust of citizens as well as an example for nations that are trying to quicken that transition. One can feel much safer under a government if one knows that information is free, and the government will not hide such personal things in the name of protecting those in power.

Fraternity, Liberty, Equality: The Hypocrisy of Emmanuel Macron’s Presidency

Macayla Moore

“The migration crisis is not really a crisis but a long-lasting challenge.”2 Immigration has been a perpetual, ever changing, and increasingly controversial topic within French politics. However, in 2017, presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron offered a compassionate approach to this heated debate. During his “Initiative for Europe” speech on September 26th, 2017, months after his inauguration, Macron outlined his initial immigration policies to protect France’s borders while addressing immigration with delicacy. The plan included establishing the European Asylum Office to settle asylum claims in six months, while simultaneously protecting France’s secular values and welcoming refugees entitled to protection. Additionally, Macron urged other European nations to remember that “it is [Europe’s] common duty to find a place for refugees who have risked their lives, and [they] must not forget that.”3 Macron offered a balance to the immigration debate, aiming to welcome refugees with humanity and ignity, and integrating French immigrants and French society into one. This speech foreshadowed that immigration would be a long-lasting challenge for Macron’s presidency. Policies regarding migration, interwoven with Islamophobic sentiments, would

soon plague and define his presidency. While he once appeared as a beacon of light against the far-right National Rally Party’s political goals, he would eventually implement policies just as deplorable.

In 2017, the election between Emmanuel Macron and far-right candidate Marie Le Pen had the lowest voter turnouts in French history with only 65.3%.4 The key issues for this presidential election were immigration and security. Marie Le Pen campaigned with an

openly anti-immigration, Islamophobic, and France- first platform. In contrast, Emmanuel Macron presented France with a fresh perspective for a strict but humane approach to immigration policy. Due to the two distinctly varying viewpoints, many French citizens were in support of neither, feeling Le Pen was far too austere and Macron too moderate. Additionally, Macron spoke against Islamophobia and the ways French policy has often unfairly targeted Muslims. In 2016, at a campaign rally in Montpelier, he claimed that “no religion is a problem in France.”5 He planned to adhere to France’s secular values, allowing “everybody [to] practice their religion with dignity.”6 However, to increase voter turnout and support from French citizens who were overall anti-immigration, Macron intensified his initial immigration policies to sway Le Pen’s supporters.

Yet, Macron implemented stricter policies than he had campaigned on. In 2018, Macron passed the French Asylum and Immigration Act. This bill accelerated asylum procedures by limiting the maximum processing time to 90 days after entering France from the former 120.8 It also doubled the maximum detention period a person without papers could be held in a detention center from 45 days to 90 days. Overall, it formally criminalized illegal border crossing.9 In November 2019, Macron and French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe vowed to “regain control” of France’s immigration policy. Phillipe stated, “When we say no, it really means no.”10 Additionally, Macron met with a reporter from the right-wing magazine “Valeurs Actuelles,” and stated his new goal “is to throw out everybody who has no reason to be here” and to make “France less attractive” to migrants.11 This led to the introduction of immigration quotas, prioritized “skilled or professional migrants,” and ceased immediate access to non-emergent healthcare.12

Subsequently, the COVID-19 pandemic struck France in January, 2020, causing detrimental effects on migrants. In 2019, France received a “high of 138,000 overall [first-time asylum seeking] applications.”13 However, in 2020, this number drastically decreased to “81,800 asylum applications.”14 Furthermore, since the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a “decrease in general asylum applications in Europe.”15 The stark decrease in applications is not the result of fewer people requesting asylum. Rather, it is due to the European Union’s restoration of their internal borders during the pandemic. COVID-19 provided the perfect excuse for France to strengthen its internal border management, limiting the entrance of citizens from other nations. Additionally, a key factor of “le confinement,” or the national lockdown, was to limit travel.16 Macron achieved this by halting “commercial flights, ending [one] of the few legal routes to Europe” asylum seekers could utilize.17 The pandemic allowed Macron to completely close France’s borders, isolating itself from the rest of the world. While the halting of asylum applications, the closure of borders, suspending travel methods, seemed extreme, they were more easily implemented under the guise of a global health pandemic. However, as people began to regain a semblance of normality and rebuild their lives, France held tightly to these extreme ideas and began to implement inspired policies.

This year Macron has continued to take steps to limit immigration into France. On January 26th, 2024, President Emmanuel Macron implemented the Law to Control Immigration, Improve Integration, the strictest immigration policy in French history. This law was heavily debated for a year after it was drafted into the Senate by Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin, who was selected and appointed by Macron in 2017. The bill was contested for months and sent to the Constitutional Council, where parliament awaited a decision on the constitutionality of the proposed law. “Out of the 86 articles presented, 47 were contested,” removing almost 40% of the original bill.20 Thirty-two articles were censured. These pertained to “tightening access to social benefits, family allowances, annual migration quotas, and housing subsidies,” placing a conditional period for residency at five years.21 They targeted family reunification, making it dependent

on “French language proficiency.”22 It affected foreign students by introducing “high tuition fees, financial deposits, verifying the nature of their studies.”23 Finally, the most contested proposition was to abolish Jus Soli, French citizenship guaranteed to any child born on French soil. Instead, the bill proposes to have these children apply for French citizenship between 16-18 years of age.

The portions of the bill that were constitutional were solidified into law by Macron on January 26th. This includes the deportation of immigrants currently residing in France if they have criminal convictions. The previous language requirement for immigrants was proof they were learning French; however, the government now requires immigrants to have an A2 level of French before entering the country.24 Furthermore, the bill focuses on resolving France’s labor insufficiencies in industries such as hospitality, agriculture, and a plethora of other sectors undesirable to French citizens. Therefore, the French government now provides a one-year work and residency permit to undocumented migrants. France has also witnessed a shortage of labor in the medical field. This new bill allows non-European Union doctors, midwives, dentists, pharmacists, etc. a guaranteed route to French residency.

President Emmanuel Macron has woven Islamophobia into his policies. France is home to 5.7 million Muslim people, the largest group in Europe.25 Despite running a presidential campaign on secularism and criticizing the former French policies that unfairly targeted Muslims, Macron has either forgotten or ignored his past sentiments. Laïcité is the French value of the separation of church and state; however, it is being used to propagate Islamophobic policies. Islamophobia has always existed within French politics; although, Macron was the first to codify it into law. Macron weaponized laïcité in the Anti-Separatism Law of 2021, which aimed to combat “Islamic radicalism” by banning homeschooling for Muslims, stricter financial controls on foreign money sent to religious organizations in France, policing places of worship, and extending the “neutrality principle” by banning symbols of religion.26 An example of this neutrality principle and abuse of laïcité occurred in August 2023 when Macron banned the wearing of abayas in school.27 Since Macron codified these systematic attacks on Islam and expressed Islamophobic sentiments, a “13% increase crimes of a racist, xenophobic, and anti-religious nature” has occurred in France since 2019.28

In 2016, President Emmanuel Macron represented hope for France. A new, youthful politician who aimed to bring peace to France, unite its citizens, effectively address the inequities rampant throughout the nation, and handle issues with carefully balanced consideration. As the 2017 election approached, many French citizens were frightened by the idea of a France under Marie Le Pen’s control. These fears were diverted then, but quickly manifested into reality under a different visage. Emmanuel Macron became consumed by poll counts, hungry for reelection and for swaying Le Pen’s supporters. This caused him to ignore the campaign promises he made by passing the French Asylum and Immigration Act in 2018. The COVID-19 pandemic allowed him to finally close France’s borders and halt asylum applications, momentarily forgetting the issue of immigration that plagues his presidency. As the world returned to pre-Covid policies, France remained strict with immigration. These anti- immigration sentiments resulted in the recent passage of the Law to Control Immigration, Improve Integration, the strictest immigration policy in France’s history. Additionally, Macron passed legislation that is blatantly Islamophobic, after initially speaking out against the unfair treatment of Muslims in 2017.

Whether consumed by the need to prolong his presidency or finally allowing the true nature of his political views to flourish, President Emmanuel Macron has held a presidency based on hypocrisy and contradiction. While many French citizens cower at the idea of a France ruled by Le Pen, they have acquired just that. President Emmanuel Macron has passed the most controversial, far right, and unconstitutional policies in French history. He continues to supply wins to Marie Le Pen’s National Rally Party, devastatingly affecting French citizens and immigrants. While he once preached for human decency and understanding, these qualities no longer exist with Macron. How can France continue to stand on the pillars of liberty, equality, and fraternity if these promises only exist to a certain demographic in France?

The Role of Food in Culture

Ben Monroe

After traveling for nine months across Morocco, Israel/ Palestine, Greece, and Germany, learning about the important relationship between culture and food came naturally. I should preface this journey has a Jewish theme, one carried out by the Gap Year program called Kivunim. Additionally, I know it’s a hard time to write about Israel/Palestine, especially considering the past few months, I just want to focus on food and culture. Considering this, let me explain a bit of the purpose and themes behind the program. The institute consisted of around 25 other Jewish American high school graduates from the ages of 18-20. In Hebrew Kivunim means directions and refers to the followers of Rabbi Akiva. The organization inspires,

“its program participants to forge a lifelong relationship with Israel and the Jewish People through travel across the world - gaining understanding of Jewish life and history together with that of the many cultures, religions and world- views amongst whom the Jewish people grew in its 2000 year Diaspora. We welcome participants from all backgrounds in the belief that mutual understanding can only enhance the possibilities for greater peace and justice across the globe.”1

Through my journey I will contemplate the role of food in comprehending the values and themes of different cultures while examining the appropriation of food in Israel/Palestine and its nuances.

A person can learn a significant amount of knowledge from the way a specific culture eats food and prepares a meal. In fact, it feels almost impossible to converse about different cultures without mentioning food. Most people love traveling and meeting new people, and sharing a meal is the obvious next step in that progression. Ironically, the most fascinating role food plays in culture is its similarity. If you take a good look, many different cuisines have a lot in common. I challenge you to think of culture or a country without the use of a form of bread. Most times a person is introduced to something new they focus on the differences, however, eating food is the perfect reminder that we are all human and we all need to eat.

The program starts with a two week long quarantine, at the end of November 2020, in an Israeli international high school called Givat Chaviva. What better way is there to learn about the food and cultures of the world than by living side by side with Israelis, Palestinians, Germans, Albanians, Australians, Ghanaians, and people from 32 different countries? There we lived alongside the other students and learned Hebrew, Arabic, and Israeli and Palestinian culture. Every day we walked to the cafeteria and ate kosher and halal meals. The lunches are meat-based, and the dinners are milk-based (kosher disallows the eating of both meat and milk at the same time). Although the food was generally not so great it acted as the perfect characterization of the school’s culture. Diverse, generous, creative, understanding, and coexistence. I should mention that the school operates within a theme of coexistence. An opinion becoming less and less popular by the day but one I hold in high regard. A month into the program it’s Thanksgiving. Most, if not all my classmates, have never missed a Thanksgiving and are rightfully feeling slightly homesick. Givat Chaviva noticed this and cooked us a Thanksgiving meal. Probably the worst tasting Thanksgiving I have ever had, understandably so, but maybe the most meaningful. Here we were, 30 Americans, taking up the school’s classrooms, dorms, library, and general privacy, but the school never got mad. They took us in and taught us their most important value of coexistence by cooking us food we were all missing. What else but food can portray so much about the culture of a place all through a simple act of kindness.

After living on a small high school campus for two months, the program gained a second wind after moving to Jerusalem. From the classic Jerusalem stone to the temple mount, we felt the history and culture of the city everywhere we went. Once settled, we continued our classes in Arabic and Hebrew and started new courses learning the history of different cultures and how the Jewish people fit among them. As an Arabic major at The Ohio State University, it is safe to say that my Arabic classes had a profound impact on me. A big reason for said impact was our Arabic professor named Amal Nagammy. Amal is an Israeli Arab from Haifa who, without hesitation, welcomed us not only to her language but to her favorite foods as well. My favorites amongst the dishes she introduced us too are Knafeh and Maqluba.

Maqluba is a dish which is flipped upside down to reveal layers of cooked rice, lamb, and vegetables.3 Amal’s passion to introduce us to her childhood dishes is entirely indicative of her identity and culture, which is characterized by the main idea of coexistence and impartiality.

Let’s discuss the elephant in the room and please know I mean no offense. When it comes to the topic of food in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict there are at least two thoughts of focus used when debating food appropriation in Israel/Palestine – thievery and unoriginality. While the language used is understandably problematic, and while I might disagree, this is not an uncommon viewpoint. According to Ronald Ranta and Yonatan Mendel Israeli food culture has cumulated in “de-Arabisation and more particularly: a total de-Palestinianisation.”4 They continue to explain by showing us one of the most popular Israeli postcards used which depicts a falafel sandwich in pita with a toothpick flag of Israel and reads “Falafel – Israel’s national snack.”4

While people throughout Israel love falafel, it is not an Israeli creation. This is not an exclusive experience but one that many Israelis and Palestinians have struggled with personally, including myself. Back in the US I went to an American Jewish school which served Israeli salad at least once a week. It was only when I visited Israel did an Israeli Jew set me straight and teach me the real name of the dish – Palestinian salad. Countries taking food from different places has happened throughout history, and the exchange of cultural dishes primarily helps two countries gain an understanding. Look at America for instance. We have Italian, Mexican, Greek, Chinese, and so many other cuisines, many of which are entirely inauthentic. However, the dangers in the stealing of cuisine lies with the rebranding of entire food cultures. Gilead Ini provides an important example where,

“Conan O’Brien made the mistake of describing shakshuka as “Israeli,” he was accosted on camera by anti-Israel activists who insisted that the eggs-and-tomato dish is really Palestinian. (It isn’t. As Libyan food writer Sara Elmusrati has explained, Sephardic Jews brought the dish from its original home in North Africa to Israel, where it’s been “showcased in a way it has never been in the Maghreb states.”).”6

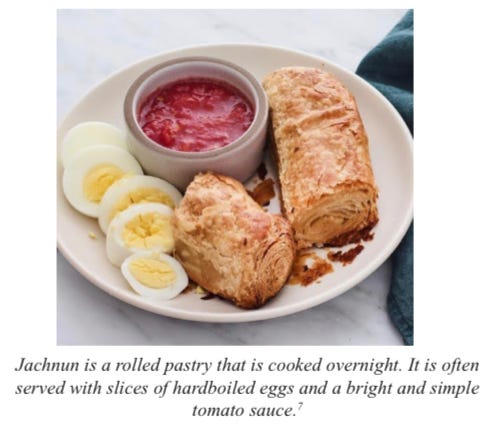

However, my favorite Jewish Israeli foods are Jachnun and Amba. There are many Jewish foods that are meant for slow cooking. During Shabbat it is customary to not use any electricity so many Jewish dishes are meant for that purpose, Jachnun is just one of those examples. Amba is a pickled mango sauce with Indian roots that many Iraqi Jews brought to Israel and is primarily used as a sauce for meat dishes. After the state of Israel was founded in 1948 Jews from around the world moved back to the holy land. Real Israeli food is a melting pot of Jewish dishes brought to Israel from the diaspora. While Israel has a problem of using Palestinian dishes and avoiding the proper respect needed when showcasing them , that does not mean there are no authentic Israeli Jewish foods or Israelis who under- stand the problem of food appropriation.

Learning about cultures through food is a wonderful and delicious experience that can enrich a person’s understanding of any culture. However, using a culture’s food without respect and dignity has potentially drastic effects. My time on my gap year

not only taught me the importance of specific cuisines but also the dangers that are represented through the misuse of culture. We all have different stories and identities so why not at least be respectful and learn something from the people who cooked unique dishes? At the end of the day, we all need to eat and we are all human.

Meet the Authors

Meet the Authors Rachel Simroth

Editor-in-Chief

Rachel is a senior studying International Relations & Diplomacy with minors in Arabic and Civic Engagement. Rachel joined Alger her sophomore year to explore her personal interest in journalism with foreign affairs and served as the Managing Editor her junior year. Her favorite Alger memory this semester was the collaboration with BlackXBold magazine on campus. She was inspired to write her Alger article on democratic backsliding in Tunisia from a previous government internship where she worked on the US-Tunisia foreign policy portfolio. On campus, Rachel is in the International Affairs Scholars Program and is a four-year member of the Ohio State Club Dance Team. She is also currently a virtual intern for the US Department of State.

Michael Sarkis

Managing Editor