Table of Contents

Letter from the Editor

Dancers and Diplomats: The Role of Dance in American Foreign Policy

The Smell of Sulfur Lingers in the Air

Silent Alliances: North Korea’s Collaborations with African Nations

Sovereignty at Stake: The impact of Chinese and Russian Influence on Remote Communities in Sahel

Assessing Proportionality In International Law

Meet the Authors

Letter From the Editor

Having been a member of Alger Magazine since August 2021, it has been my pleasure to see the organization evolve since then and an even bigger honor to lead it this year as Editor-in-Chief. One characteristic that has always stood out to me about Alger Magazine is the diversity of people it brings together - and with that comes an important mixture of perspectives, news, and new sources. Quality journalism and press freedom around the world must continue to champion this diversity of thought.

Our publication is different from past years as this is our first year with a semiannual publication, with this being our first Winter Edition. The articles cover a range of broad and niche topics in international affairs, but going through the submissions, there was a theme that stood out through all of them: Repercussions. What are the geopolitical and personal effects of public diplomacy programs? What have been the subsequent consequences of Bush’s decision to invade Iraq twenty years ago? What are the results for Africa with growing North Korean, Chinese, and Russian influence on the continent? What is a proportional reaction? Our writers this semester explored these intriguing and bold questions. A big thank you to the writers for their hard work and well-written articles, and to everyone who attended the Alger Magazine meetings.

Many thanks to the incredible managing editors at Alger Magazine, Abriana Malfatti and Michael Sarkis, for their hard work this past semester. I could not run this magazine without your support and contributions, and I want to recognize your tremendous value to this Alger team. We all hope you enjoy reading this magazine as much as we did making it.

My final thank you goes to Imaan for helping me brainstorm the cover design for this publication. She is a teenager from Aleppo, Syria whom my mother works with through a refugee volunteer assistance program after Imaan moved to my hometown in New Jersey early last year. She loves art and enjoys drawing and sketching out characters from books. The arts — from drawing to music to dance to writing — play several valuable roles in foreign affairs. They present a unique interpretation of international affairs. They are an outlet for youth and capture the importance of the civilian voice. And the arts, especially through writing in the form of journalism, work to shed light on some of the worst political and humanitarian conflicts of our generation. Amidst democratic backsliding and wars globally, the work and safety of journalists must remain protected, and we all must continue to recognize the important role they play in our world.

Sincerely,

Rachel Simroth

Editor-in-Chief

Dancers and Diplomats: The Role of Dance in American Foreign Policy

Rachel Simroth

“This is a diplomatic mission of the utmost delicacy. The question is, who’s the best man for it – John Foster Dulles or Satchmo?” A 1958 Mischa Richter political cartoon comparing the American Secretary of State to an artist may appear as a perplexing power comparison at first glance. Yet, musicians and dancers represent vital foreign policy instruments for the American government in its cultural diplomacy efforts. Cultural diplomacy is a build-bridging performance on the world stage. Diplomats seek to forge connections and mutual understanding between countries through the cultural exchange of arts and education while simultaneously promoting American values and policies.

Through the Cold War and into the twenty-first century, the Department of State sponsored several American dance companies’ performances around the world. Dance diplomacy programs abstractly promote US geopolitical objectives as they often lay a foundation for future US diplomatic outreach - from American dancers performing for Kenyan post- colonial leader Jomo Kenyatta in 1967 to dancing in Myanmar in February 2010 as the Obama administration sought to expand US-Burma relations. The State Department sent Alvin Ailey Dance Company on an Africa tour in 1967 to “explicitly [bring] together African and African American self-determination movements” and hope that “African audiences would be inspired by the American presence to bend African post- colonial movements towards American democracy.”2 That tour also includes stops in several recently decolonized African nations “where the United States worried about increasing communist leanings.”3 More recently, Myanmar was one of the first countries targeted by the Obama administration to increase communications with, and its new relationship with Myanmar became a key building block of Obama’s Asia policy. A year after the ODC Dance Company performed, President Obama announced a major shift in US policy towards Myanmar, and three years later, in 2012, President Obama and then Secretary of State Clinton made a widely publicized visit to the country.4 Dance is a unique diplomatic vehicle as it allows the United States to communicate — both intellectually and emotionally — with international audiences without requiring a shared language.5 These dance exchanges are a “coupling of the physical and political” and “help us see how people come together in social networks, a central concern for policy.”6 Dance has been an important soft power tool for the US as artistic exchange builds networks between civil societies abroad and Americans.

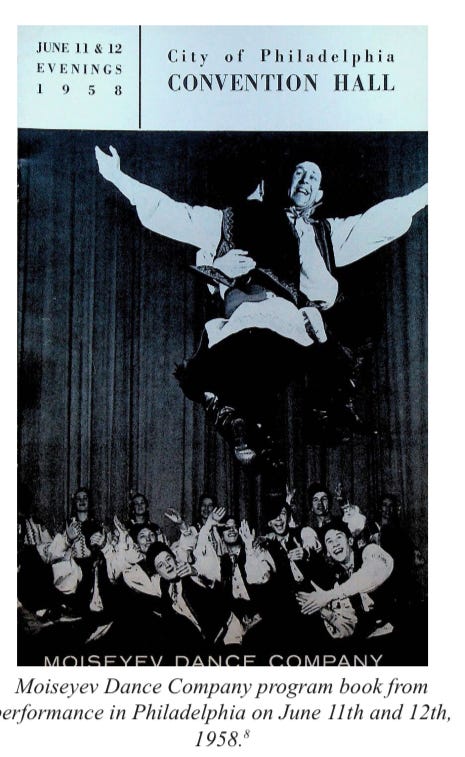

Dance diplomacy first entered the stage in American foreign policy as a means to compete with the Soviet Union's cultural outreach programs during the Cold War. The bilateral 1958 Lacy-Zarubin Agreement allowed cultural, educational, and scientific exchanges between the US and the Soviet Union. In the spring of 1958, the Russian Moiseyev Dance Company performed in cities across the United States. With those performances, the company sought to present a positive picture of a unified Soviet Union, incorporating folk dances from multiple cultures - Ukraine, Azerbaijan, and Poland - within the Soviet sphere of influence.7 Moiseyev’s performances were

met with immense enthusiasm from American audiences, with its first performance in New York sold out and an additional four days of performances were added in the larger venue of Madison Square Garden to accommodate demand.9 The Russian dancers both fascinated and frightened American audiences, as the Dance Magazine's June 1958 edition wrote how "it is extremely clear that a large part of the American public is enjoying, and being affected by, Russian propaganda currently here in the form of Moiseyev Dance Company.”10 The tour produced newfound empathy towards the people of the Soviet Union, resulting in cooler tensions during this period of the Cold War. In response, the US sent the American Ballet Theater to tour the Soviet Union as cultural representatives of American life and excellence to make respective impressions.11 In this moment, the US government had become well aware of the power cultural diplomacy programs had in projecting American soft power in the Cold War. In 1959, the State Department persuaded President Eisenhower to establish the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Relations within the State Department to better coordinate all US cultural exchange programs.12

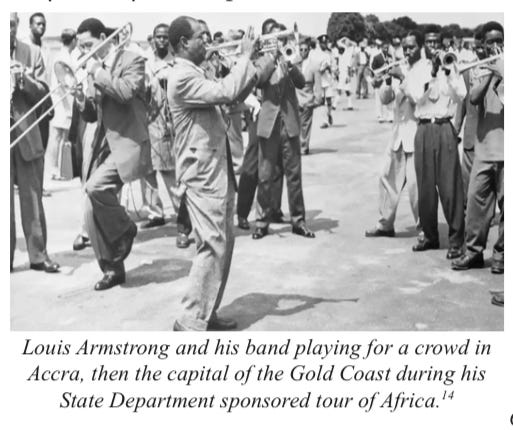

These Cold War artistic exchanges promoted a nation’s cultural values in contrast to the other superpower. The Soviet Union outlawed American music genres, like jazz and rock and roll, as officials criticized it as culturally corrupt.13 On the other hand, in October 1960, Louis Armstrong — a famous American jazz trumpet player — embarked on a three-month Department of State tour of twenty-seven cities in Africa to “power- fully convey his deep sense of connection to

African peoples and their shared aspirations for freedom.”15 The US government sent Armstrong to Africa at a time when the world was captivated by American jazz and blues. America capitalized on the pleasure of American jazz music to build support for American values and policies that directly contrasted with the Soviet Union’s view of the world.

The style of dance promoted by each superpower conveyed the contrasting cultural and political values of each country. With the United States standing as the center of modern dance, the "free- flowing movement of modern dance was thought to represent the liberty of the US" in contrast to the communist Soviet system. Martha Graham’s American modern dance company performed Appalachian Spring globally, with it premiering in Vietnam in the 1950s. This piece sought to romanticize America’s frontier heritage and push the cultural values of self-reliance, individualism, American toughness, and capitalism. Conversely, the world-renowned Russian ballet schools and the "virtuosity of Soviet dancers show[ed] the fruits of collectivism.” The Russian company Bolshoi Ballet performed Spartacus during its tours around America, a ballet piece about a slave uprising and the proletariat. It intended to both critique racial inequality in the United States and promote communism.16

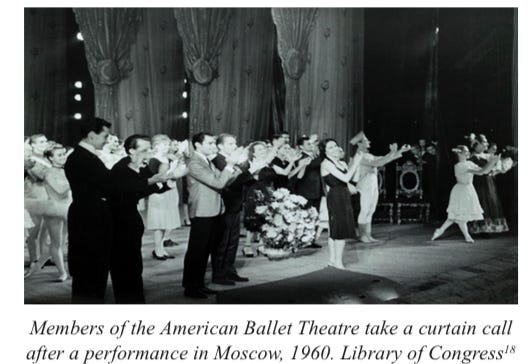

The power and beauty of dance diplomacy lie in its ability to form human connections between civilians, even at their government’s most volatile political moments. In October 1962, the New York City Ballet Company was one week into an eight-week State Department-sponsored Soviet tour when US planes identified Soviet missiles in Cuba. Military tensions between the US and the Soviet Union escalated rapidly just as the US ballet company began performances at the Palace of Congresses Theatre, located in the heart of the Kremlin complex.17 US embassy

staff reportedly warned the dancers to expect a hostile audience given geopolitical world events – yet the opposite occurred. “Bis! Bis! Encore! Encore!” the audience shouted as the American dancers received a standing ovation from three thousand Soviet citizens. US principal dancer Edward Villella even defied his dance company policy forbidding encores that night and returned to the stage to repeat his solo from George Balanchine’s Donizetti Variations.19 Two narratives were present in the Kremlin in October 1962: one by American ballet dancers building bridges with the Soviet citizens over their mutual love of ballet, and the second was down the street as Soviet Union officials negotiated with their US counterparts, with “both sides acting on the belief that Soviet and American ways of life were absolutely incompatible.”20

Although Cold War dynamics provide a historical understanding of the birth of cultural diplomacy programs in American foreign policy, their purpose is to create spaces for cultural understanding and collaboration, not competition. In an interview I conducted with Helena Finn, former Acting Assistant Secretary of State for Educational and Cultural Affairs at the Department of State and current Chair of the Board of Directors of Battery Dance, she “found ways to use cultural diplomacy to create a bridge between audiences on the opposite sides of long-standing conflicts.”21

While serving at the US Consulate General in Lahore, Pakistan, Helena organized a conference on postmodernism and invited participants from India. Participants included an Indian scholar of American literature, a notable Indian Jewish poet, a prominent dancer and scholar of dance — Millicent Hodson — as well as Pakistani artists, dancers, writers, poets, and musicians. Helena chose this topic because “it was at the center of academic and scholarly discussion at the time” and the event was “centered on the arts, rather than politics,” such as debates on the conflict between India and Pakistan. It can be difficult to quantify the success of cultural exchange programs. Yet Helena noted that “for the Indians who had lived in Lahore before Partition, this was an opportunity for an emotional reunion with their former classmates.”22 In this instance, a US artistic exchange embassy event aligned with US policy objectives of de-escalation on the border with its valuable policy objective of humanizing participants on either side of the conflict.

Dance diplomacy programs also emulate conflict resolution political objectives within American foreign policy. Upon arriving at her posting as a Counselor for Public Affairs at the US Embassy in Tel Aviv from 2003- 2007, Helena “realized that Jewish and Arab young people had very little contact with one another.” Having previously met Jonathan Hollander, the Founder and Artistic Director of Battery Dance, she felt Battery Dance’s focus on mutual understanding “was an ideal fit for our cultural diplomacy mission to promote peace.” As a US embassy official, she organized the following program:

“The dancers came to Jaffa and worked with young people from both communities to create original works. These were then performed before audiences that brought together parents and other guests from both communities. It was an exhilarating experience that confirmed me in the conviction that people who hold very negative preconceptions about other can over- come them through joint participation in programs that enable them to truly express their feelings.”23

Aligning with the American political and economic policy objectives in the region, Helena noted her project followed “in the spirit of the larger Wye River Project created during the Clinton Administration that provided funding to put Israelis and Palestinians in projects devoted to education, water management, technology, archeology, agriculture, and other areas of common interest.”24

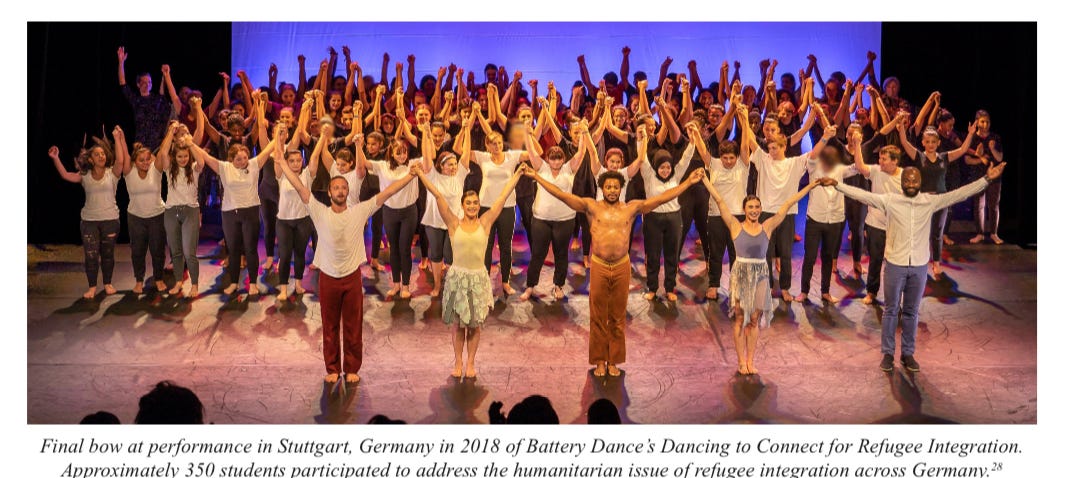

US dance companies repeatedly work in collaboration with the US Department of State to foster this type of engagement within local communities around the world. As Minister-Counselor for Public Affairs at the US Embassy in Berlin from 2007-2010, Helena said she noticed “the children of the immigrant and asylum communities [with roots in Turkey, the Middle East, and Africa] were having difficulty relating to their German counterparts.” In response, the US embassy arranged to work with a local high school in an immigrant neighborhood that also housed a local population of ethnic Germans. Helena turned to Battery Dance again, commenting that “Battery Dance does something uniquely American” as it “encourages the students to create their original works” in contrast to other dance companies that only trained other dancers. Battery Dance conducted dance workshops for the students, and “at the end of the workshops, we held a performance to which the parents were invited. These immigrant parents glowed with pride to see their children on the stage in a German high school.”25 Through this program, a US dance company was able to foster refugee assimilation at the community level. The work of refugee integration and community engagement remains critically important in Germany today, particularly given recent reports that right-wing extremists —

including members of the far-right AfD political party — met to discuss the deportation of millions of immigrants, including some with German citizenship.26 Battery Dance is one of several organizations contracted with the Department of State to pursue similar diplomatic public outreach aims over the years. DanceMotionUSA was an international dance touring program of the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs administered by BAM (Brooklyn Academy of Music). Formed in 2010 and active until 2018, BAM worked with US embassies in 56 countries. US-based dance companies were sent out on month-long tours focused primarily on community engagement, with American dancers offering free public performances, providing workshops, and taking master classes with local dancers.27

As both a dancer for eighteen years of my life and a person pursuing a career in foreign policy, dance diplomacy strikes a personal note with me. I was first introduced to the practices of dance diplomacy by a former Russian diplomat in her dance studio in Amman, Jordan. I lived in Amman for a summer studying Arabic at AMIDEAST, a US non-profit organization dedicated to cooperation and mutual understanding through language training. Recommended to me by a UN employee I met in Amman who was also a dancer, I signed up for a ballet class that met twice a week in the evenings. After one of the classes, I stayed behind in the studio and talked with the ballet teacher about her life. She told me how she moved to Jordan decades ago to work for the Russian Embassy in Amman as her government wanted to promote ballet to the Jordanian public as a form of cultural diplomacy. In the following weeks, I found myself reading in cafes in Amman article after article to understand dance diplomacy. That moment inspired me to do my final Arabic class presentation that summer on how both the US and Soviet Union used

dance diplomacy in the Cold War to further their foreign policy interests. Dance diplomacy is not a uniquely American or Russian expenditure, and what makes it effective is the natural mutual understanding it fosters. Before that ballet class, I took a Dabke dance class twice a week in the evenings, taught fully in Arabic, on the rooftop of a dance school in northern Amman near my host family’s house. That class was an insight for me into Levantine culture through dance and music, and allowed me to engage with locals even though I was not fluent in Jordanian Arabic.

My time in the Middle East shed light on the diplomatic uses of artistic mediums in American foreign policy. Cultural diplomacy fosters these valuable people-to-people interactions that form the basis of connections and cooperation with civil society - beyond the military aid deals and the high-level government agreements. Cultural exchanges cultivate empathy, a currency used prior to brokering political diplomatic achievements and which has given a face to American power in the post-World War II era. Different American administrations award varying levels of attention to funding these initiatives. Yet, with polarization and authoritarianism on the rise globally, I believe cultural exchanges should be increasingly important. With this, I asked Helena - who was responsible for overseeing all US global and educational cultural exchanges at the State Department in the early 2000s - where she thinks the State Department should focus on sending dance companies today: “The Bureau should focus on all regions of the world by working closely with the regional Bureaus of the State Department. Programs for wealthy nations can be coordinated through public-private efforts in cooperation with entrepreneurs. For the countries in the middle tier, as well as the countries that suffer from extreme poverty, funds must be made available to promote cultural exchange.”29 The FY 2023 Request for the Public Diplomacy Bureau in the State Department was $701.4 million, covering global efforts to expand and strengthen the relationship between the US and citizens of other countries.30 These cultural exchanges exemplify how the universality of art, music, and dance foster empathy at the individual level around the globe. These artistic exchanges are remarkable as they promote continued dialogue between different nations, all without the need for the same language.

So now I ask the audience again: This is a diplomatic mission of the utmost delicacy. The question is, who’s the best person for it: Diplomats or dancers?

The Smell of Sulfur Lingers In the Air

Abriana Malfatti and Michael Sarkis

In September 2006, Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez began his speech at the United Nations General Assembly meeting: “The devil came here yesterday,” and that “it smells of sulfur still today.”2 Yet, Ecuadorian Presidential Candidate Rafael Correa condemned Chavez for comparing President Bush to the Devil at the United Nations General Assembly meeting.3 He thought it was an insult to the devil.4

While President Bush is not the devil incarnate, he has egregiously violated The Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UNCAT). The Convention established on June 28th, 1987 utilized former international law such as the UN charter and the Univeral Declaration Of Human Rights to “make more effective the struggle against torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment throughout the world.”5 While the Bush Administration committed numerous violations of international law during the Iraq War, this article will focus on the administration’s violations of UNCAT. Bush and his administration deserve to be prosecuted in a court of law for their violations of UNCAT as the United States must take a stance against impunity in order to uphold international law. Two pathways towards justice will be examined in this paper: the domestic route and the International Criminal Court. This article will examine what aspects of The Convention Against Torture were violated and debate the ideal solution for international justice.

Legal Framework

With regards to our legal argument, we used the following legal definition of torture from UNCAT to construct our analysis:

“Any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third per- son information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.”7

The rest of our legal argument will use the UNCAT definition to demonstrate why the Bush administration’s actions during the Iraq War were not justified under international law.

The first use of torture can be seen following 9/11, when the US military and CIA interrogators were instructed to take a gloves off approach to handling captured or detained individuals.8 To help the interrogators in this mission and to avoid legal trouble, the US Department of Justice Office of Legal Counsel narrowly defined torture to allow the following methods: waterboarding, wall-banging, sleep deprivation, slapping, shaking.9 Alongside the authorization of these torture methods, then Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld authorized having subjects stand for up to four hours without a break.10 The US utilized black-sites — secret prisons in Europe and Asia — to keep high value Al-Qaeda prisoners for extended periods of time.11 Survivors of these black-sites report the use of torture, such as the case of Khalid El- Masri. In December 2003, El-Masri was taking a bus ride from Ulm, Germany to Skopje, North Macedonia, when he was detained by Macedonian guards and later handed over to CIA custody.12 Under the impression that El-Masri was a high-profile target, the CIA transferred him to a secret CIA prison outside of Kabul, Afghanistan known as the “Salt Pit,” even though the CIA was aware that was innocent during his transfer to Kabul.13 He remained in brutal conditions until May 2004, when he was blindfolded and deposited on a mountain road in Albania.14

The formation and measures employed at these CIA black sites represent the overall dismissive attitude the Bush administration had towards respecting international law. These methods of torture were utilized throughout the Iraq War, according to the Human Rights Watch, “After the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, the US and its coalition allies held about 100,000 Iraqis between 2003 and 2009. Human Rights Watch and others have documented torture and other ill-treatment by US forces in Iraq.”15 These actions not only fit UNCAT’s definition of torture, but the actions of the administration during the Iraq War were not sanctioned by any UN governing body. According to Dr. Alexander Thompson in his discussion of the second Iraq War, “there is no doubt that the overwhelming impression of leaders and their publics around the world was that the war was fought without Security Council backing and, indeed, that it was fought against the vocally expressed wishes of most UNSC member states. Thus both legally and practically, it is safe to characterize the Second Iraq war as having been conducted without IO (international organization) approval.”16 Given this, any and all actions taken by the Bush administration during this period in regards to torture are illegitimate and fall within the violation of basic international law.

In addition to violating the basic definition of torture under international law, the threat or act of war (legitimate or not) is not a permissible excuse for any type of torture. Article 2.2 of UNCAT explains, “No exceptional circumstances whatsoever, whether a state of war or a threat of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked as a justification of torture”.17 Article 2.3 of UNCAT goes even further clarifying that, “An order from a superior officer or a public authority may not be invoked as a justification of torture.18 Bush and his administration were in clear violation of international law and there is absolutely no justification for their actions, especially since the claim of Iraq harboring weapons of mass destruction was false.

President George W. Bush’s Involvement

Debates have swirled over if President Bush was aware of or authorized the use of these torture policies by his own administration. According to a 2014 Senate Committee on Intelligence Report, Bush was not fully briefed on the CIA torture program until April 8, 2006.19 The Senate Report states that “CIA records state that when the president was briefed, he expressed discomfort with the ‘image of a detainee, chained to the ceiling, clothed in a diaper and forced to go to the bathroom on himself.”20 Along these lines, John Rizzo - the CIA’s top lawyer at the time - reports that George Tenet - the director of the CIA - told him: “I have no recollection of ever briefing President Bush about the techniques at that time,” referring to the interrogation of Abu Zubaydah, who assisted Al-Qaeda in coordinating its attacks, in 2002.21 However, President Bush and Dick Cheney’s statements contradict the Senate Report and George Tenet. In his memoirs, President Bush wrote that, in 2002, Tenet approached him regarding the interrogation of Abu Zubaydah, and in turn, President Bush requested new interrogation methods from his team to elicit information from Abu Zubaydah.22 President Bush then supposedly had the Department of Justice review the legality of these new techniques, and afterwards Bush claims to have taken a look at the list of interrogation techniques, writing that “there were two that I felt went too far, even if they were legal. I directed the CIA not to use them.”23 Additionally, former vice president Dick Cheney said that the Senate Report was “full of crap” and contradicted President Bush’s statements, saying President Bush knew about the techniques used by the CIA, and everything he needed to and wanted to know about the CIA program.24

Towards the Transvaluation of the ICC

According to Section 2340A of Title 18 of the United States Code, public officials are prohibited from committing torture against any individual persons within their custody or control. The statute defines torture as “acts specifically intended to inflict severe physical or mental pain or suffering” and only applies to torture committed outside the United States.25 Alongside this statute, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld allows for the enforcement of the Geneva Convention within US law. Osama bin Laden’s former chauffeur, Salim Ahmed Hamdan, filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus to challenge his detention in the notorious Guantanamo Bay. Yet, before a federal district court could examine his petition, he was deemed an enemy combatant by a military tribunal. However, the federal district court would eventually grant Hamdan his petition, ruling that before he could be tried before a military commission, Hamdan must be granted a hearing to determine whether he was a prisoner of war under the Geneva Convention.26 The Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia overruled the lower court’s decision, ruling that the Geneva Convention could not be enforced in the federal courts and that the establishment of military tribunals was authorized by Congress.27 Hamdan’s case was brought before the Supreme Court, and on June 29, 2006, in a 5-3 decision it ruled that the military commissions were not authorized by Congress or by the inherent powers of the Executive. As a result, military commissions were required to comply with the ordinary laws of the United States and the laws of war, which allowed for the application of the Geneva Convention in the US. Given that the Supreme Court allowed for the application of the Geneva Conventions within the United States legal system, it may be possible to prosecute President Bush for violating the UNCAT and Section 2340A of Title 18, USC.

An important question still remains: why should President Bush be tried in the US and not by the ICC? The reason can be found within the jurisdiction of the ICC and the principle of complementary. The ICC only has jurisdiction over crimes that were committed by a state that is party to the Rome Statute, in a state that has accepted the Court’s jurisdiction or in the territory of a party to the Rome Statute.28 The Court can also claim jurisdiction over crimes that were referred to the ICC Prosecutor by the United Nations Security Council according to a resolution that was adopted under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter.29 Based on this, the ICC lacks jurisdiction over many of the crimes committed by President Bush. Currently, the United States is not a member of the Rome Statute, and neither is Iraq, thus denying the ICC jurisdiction to prosecute Bush’s crimes within the US, US territories, or Iraq.30Similarly, since the US is a member of the Security Council, it can veto any resolution that would seek to subject the United States to the ICC’s Jurisdiction.

While Afghanistan is a member of the Rome Statute and therefore the ICC has jurisdiction to prosecute Bush for war crimes committed the US could escape the ICC’s jurisdiction through the principle of complementarity, found in the preamble and Article 17 of the Rome Statute.31 This principle states that if a State announces that it will be pursuing its own investigation, within one month of being told that the ICC Prosecutor is pursuing an investigation, it can avoid the ICC’s investigation.32 Thus, to escape the Prosecutor’s jurisdiction, the US would simply need to conduct its own investigation into any crimes it may have committed in Afghanistan. Given these circumstances, the only way Bush could be tried by the ICC would be with a referral by the UN Security Council or the unwillingness of the United States

to open an investigation against Bush. The former is unlikely to happen since any of the permanent five members of the Security Council could veto any resolution that would address the matter. The latter is more likely to occur and bring President Bush Bush within the ICC’s jurisdiction, assuming that the involved parties cooperate with the ICC. However, even if the ICC opened up an investigation against and chose to prosecute President Bush, the United States would not hand him over to face trial. In addition, it is dubious as to whether handing President Bush over to the ICC would set a precedent for world leaders and countries to be held accountable more than they already are, as the ICC has already attempted to do so and has demonstrably failed.

This failure is exhibited through the ICC’s near sole focus on prosecuting crimes in Africa, earning the nickname “Court for Africa.”33 This problem stems from not from the ICC itself but rather from the fact that powerful nations will not subject themselves to prosecution by the ICC. For example, in 2011, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1973, authorized member states to enforce a no-fly zone in Libya and take whatever action was necessary to protect civilians and civilian populated areas from attack.34 This allowed NATO countries to intervene, but strangely, the resolution included language that provided immunity from prosecution or investigation for NATO allies.35 This exemption from prosecution for Western powers predates the ICC. The International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia did not investigate NATO’s 1999 bombing of Serbia, which may have caused significant civilian death and violated international law, because NATO was uncooperative in any attempt by the Tribunal to investigate the bombing campaign, making it impossible to build a case.36 Due to these instances demonstrating the inability and unwillingness of the ICC to prosecute Western powers, it does not follow that a precedent would be set if the US handed over Bush to the ICC for prosecution. Instead, if the US decided to hold President Bush accountable for his actions, it would be more reasonable to try him domestically as there would be logistical roadblocks in handing him over to the ICC.

An Argument In Favor of International Justice

The United States cannot consider itself to be a global leader of justice and democracy when it fails to uphold international law. This section of the paper will argue why it is in the best interest of both the United States and the international community to set a precedent of holding their own leaders accountable for violations of international law, this means that there is in fact a benefit to cooperating with international court systems. Signing the Rome Statute would allow the United States to uphold its own state sovereignty while simultaneously being an active member of the international community. As described above in the situation where NATO refuses to cooperate with international law, the current system of impunity is hurting the legitimacy and effectiveness of the international system. If we want international law to be followed, it not only requires states such as the United States to show willingness to cooperate, but requires a severe attitude change that seeks to uphold justice and human rights above state power politics. All legal systems have limited resources and are imperfect. Rather, it is more effective to prioritize having a legal system that offers at least some type of hope and accountability in the face of tragedy rather than disregarding the system completely.

The ICC is an integral part of the international community to safeguard the world against impunity of the most horrific crimes. According to UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, the entire point of the ICC is to “ensure that no ruler, no state, no juana and no army else where can abuse human rights with impunity. ”37 The standard of preventing impunity within international law cannot be understated, especially when the stakes are so high. When discussing impunity in the global system, Dr. Christopher Whelan writes that “impunity may have encouraged Hitler to pursue the Holocaust and to encourage his troops, as they crossed the Polish border, to show no mercy to the Poles. He famously or infamously-specifically said to them: ‘Who after all, speaks today of the extermination of the Armenians.”38 In other words, the old cliche that “those who do not learn from history are bound to repeat it” applies here. The United States failing to uphold the ICC severely weakens the legitimacy of the international system and American global leadership, especially since the United States was one of the proponents for pushing the court forward.

The current relationship that the United States has with the ICC creates and reinforces a double standard of international justice that is not productive to any nation. Dr. Whelan effectively pointed out America’s historical double standard on international justice, noting that not only was the United States one of the initial supporters of creating an international criminal court, but they also “played a major role at the international conference that negotiated and finalized the Rome Statute in 1998.”40 In addition to setting up the court, the United States has a history of both backing ICC missions and hunting down other nations leaders’ who are responsible for violating international law. The example he used to demonstrate this very point involves the man himself: George W. Bush. During his administration, President Bush appointed Pierre-Richard Prosper to be responsible for gathering a portfolio of war crimes committed by Felicien Kabuga. At the time, Kabuga was a wanted criminal at the international scale as he was suspected of funding the Rwandan genocide. This international effort had full US backing with Bush and Secretary of State Colin Powell using resources such as the FBI and CIA to aid in bringing Kabuga to justice.41 Bush was willing to put US resources toward the international community to further international justice against impunity, but would not keep the same mentality when it came time for the United States to answer for their own crimes.

President Bush was well aware of his critics. In 2011, it was “suspected that George W. Bush canceled a speech in Switzerland in February of 2011, because two alleged torture victims were ready to file a complaint against him as soon as he landed.”42 Bush’s message to the world is clear: he hides from the law and thinks that he is above it, even three years after his presidency ended. One cannot look to them as outstanding world leaders when they use the international system to make themselves look righteous while simultaneously evading justice when it comes time for them to answer for their own crimes.

Intersection of Domestic and International Law

One of the biggest misconceptions about the ICC is that it is primarily internationally focused. This is not true, as the ICC is designed to uphold international law at the domestic level before getting the international community involved. This can be seen throughout the Rome Statute. For example, in Article 1, which establishes the court and its jurisdiction explains that, “It (the court) shall be a permanent institution and shall have the power to exercise its jurisdiction over persons for the most serious crimes of international concern, as referred to in this Statute, and shall be complementary to national criminal jurisdictions.”43 This is also aided upon by the entirety of Article 17 of the Rome Statute which talks about inadmissibility. Article 17.1 describes a case as becoming inadmissible to the international court if “The case is being investigated or

prosecuted by a State which has jurisdiction over it, unless the State is unwilling or unable genuinely to carry out the investigation or prosecution.”44 This means that the idea of the ICC predominantly being made up of trials and investigations only in Geneva is false. The language of the Rome Statute is clear in that states may be responsible for handling their own investigations and determining if a case is even admissible to be considered under the jurisdiction of the Rome Statute. They are also well in their right to decide to not even prosecute an individual, as long as they have an investigation, “ (if) The case has been investigated by a State which has jurisdiction over it and the State has decided not to prosecute the person concerned, unless the decision resulted from the unwillingness or inability of the State genuinely to prosecute.”45 What this means is that the Rome Statute does in fact uphold state sovereignty by allowing the government to choose whether to prosecute an individual. The only time in which the ICC would have jurisdiction to step in is if a state is refusing to make any efforts to investigate an issue of a severe violation of international law.

The United States would not be giving up its power by working through the international court system. Rather, they would be demonstrating how international law and domestic law can work in tandem to protect basic human rights and safeguard against impunity. This means that it is entirely possible to have a trial at the domestic level as talked about above, but instead of using domestic law, they would have a stronger arsenal of international law to back their efforts. Another way to think of the Rome Statute is that, rather than giving a nation’s leader up to the international community, signing and abiding by the Rome Statute means a nation is choosing to hold its own leaders accountable on their own terms. It gives nations the chance to be successful world leaders by setting precedent for international law using domestic courts. Rather than focusing on the fact that nations currently do not practice holding their own leaders accountable for international crimes, we should focus instead on a method that would ensure a better future. Just because something was never done in the past does not mean that it will never happen in the future.

The case with President Bush shows us why the United States has yet to join the ICC, and that is because the US is able to completely evade justice. No country is free from corruption, not even the supposed land of the free. Article 17 clause 2 sub-clause a, directly acknowledges this when explaining that the international court would intervene in a domestic hearing if “The proceedings were or are being undertaken or the national decision was made for the purpose of shielding the person concerned from criminal responsibility for crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court referred to in article 5.”46 Since there have been absolutely no efforts by the United States to even prosecute the Bush administration for their behavior overseas, it can be reasonably inferred that Bush’s legacy is protected. Not joining the court allows nations to live with impunity, it leaves nations to decide when a law is broken and who is deserving of jus- tice. What entitles any leader to deem that their lives are more important than the 8.1 billion people across the globe? The actions of the United States when it comes to upholding international law stink of bad legal precedent that continues to harm the integrity of the international system by telling the world that there are people who are above the law.

Conclusion on the Benefits of the ICC

Despite all of the faults of the international system, there is a benefit to joining, especially if the concern is over state sovereignty. Joining the ICC would not make the United States appear weak; instead it would make them look stronger if they decided upholding the law is a priority. The United States does not have a completely negative relationship with the court either. They were one of the first endorsers for an international court and helped draft the Rome Statute. In addition to this, “US federal courts have surprisingly referred to the ICC on at least 60 occasions.”47 The United States’ domestic values on justice align with the values of the court. If the United States truly is committed to preventing impunity and upholding justice, then it needs to be engaging members of the international community. They cannot keep declaring that the entire world should be held responsible for their crimes while claiming immunity for themselves and expecting to be regarded as strong global leaders.

Overall Conclusion

Throughout this piece, we address several hypotheticals, and the question arises of what is the point of discussing these hypotheticals when, as we admitted above, they are unlikely to happen. This is a justified question. We would say that the purpose of entertaining these hypotheticals is that they allow us to determine the world we want to live in and the barriers and paths that are necessary to reach it. We discuss the numerous flaws plaguing the international system, but through the diagnosis of these flaws, we can chart a path forward. While the system may be broken, it does not mean that it must remain broken. The current legal systems can be utilized to hold leaders accountable, and it is up to us to utilize them. We are told to be content with a system that lets war criminals live out their golden days as successful painters, but we say no and choose to challenge the status quo. Whether it be at the domestic level or the international level, we should never stop conceptualizing ways to hold our leaders accountable for their actions. Refusing to challenge the status quo furthers impunity, making the world doomed to repeat its mistakes.

Silent Alliances - North Korea’s Collaborations with African Nations

Elizabeth Apple

Introduction

This research investigates the extent of North Korean (NK) proliferation-related activities within the African continent, and explores the underlying motivation that drives these activities. Proliferation-related activities will be defined as activities that could further advance North Korea’s own nuclear power and other countries’ military power. The primary methods that will be discussed will relate to general revenue generation and NK’s tactics for evading sanctions. Other means that support proliferation could include equipment and technology procurement, and offering arms or other paraphernalia that could be used for the military.

The relationship between the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) and African nations initially began during the Soviet Era. During the Soviet Era, North Korea supported decolonization of various African nations by being in favor of the black liberation movement and independence. The DPRK’s support to Africans initiated diplomatic and economic relationships that would last decades long.1

According to a news and international relations reporting site, Countercurrents, Mwandawiro Mghanga (a Kenyan politican, a representative of the Social Democratic Party) discussed the DPRK’s presence and support during the liberation movement and after, around the 1960’s. He allegedly said:

“Immediately after independence from colonial- ism in the 1960s, thousands of Africans, including Kenyans, received free higher, technical and specialized education in the DPRK. DPRK not only offered arms, finance and other material solidarity to Namibia, South Africa, Angola and Mozambique in the war against apartheid and imperialism, but it also actually sent internationalist revolutionaries to Africa to fight side by side with Africans for Africa.”2

Mghanga’s quote supports the notion that the support from the DPRK extended during such a revolutionary and pivotal period in Africa – which in turn cultivated a relationship that would endure for a long period of time. The DPRK played a crucial role in providing assistance in various events and in different ways to aid Africans against imperialism. The anti-imperialist stance adopted by the DPRK is likely rooted in the Japanese imperialization in the Korean Peninsula. In addition, it is likely that the Republic of Korea cooperating with western nations, such as the United States, likely intensified the DPRK’s sentiments of disdain towards the West, further solidifying their commitment to aiding and empathizing with the African nations in their pursuit of independence. With a shared adversary, there was and is still an incentive to support Africa.

The DPRK, a nation distinguished for its solitude, has been quietly making its imprint in various African countries. Various African nations have been facilitating progress of the North Korean regime’s interests in strengthening their government and military power by various means. The ways that the African-North Korean relations are being fostered offers insight to the vulnerabilities and points of fragility of both nations. In regard to North Korea, the prime point of fragility would be finding sources of income, whereas the African states’ vulnerabilities could be within their lack of security, technological or weaponry advancement, raw or material goods, or workforce where they feel the need to engage with the DPRK as opposed to more stable, humane foreign partners.

So why do nations engage in business with the DPRK despite the well known human rights violations, corruption, and criminal history that is correlated with Kim Jung-Un’s regime? Quite simply put, the DPRK collaborates with nations that are in need of resources, aid, labor, and trades because these nations often are isolated or do not have means to source from a better nation. Furthermore, the enforcement of UN sanctions are not as strict as there is a lack of UN inspectors to enforce the sanctions.3 In addition, it is often cheaper to have deals with North Korea, and allegely easier to trade with as the nation is known to ask few questions.4

Significance

Investigation and emphasis on the DPRK’s sanction evasion and military proliferation efforts are of great importance for compelling reasons. Given the number of sanctions that are present against a significant number of DPRK entities, it raises concerns of how Kim Jong-Un’s regime is able to maintain a flow of income to fund his military and nuclear programs. Being attentive to the regime’s means of income can allow one to be wary of the loopholes that the regime is using, so that those means can be surveilled to either further prevent their generation of income or to monitor the income for the sake of being able to anticipate their future activities. Secondly, tracking down the countries that are involved with facilitating NK business and are disobeying the sanctions are vital to being able to have a better idea of dynamics in the global political stage. It is to the US’ benefit to be aware of how foreign states are diplomatically aligned.

Dissecting the means of income of the isolated nation can give analysts, researchers, policymakers, and political scientists an insight of vulnerabilities for sanction evasion not only for NK, but also for other countries with sanctions.

Knowing which countries are involved with faciliating business and income with the DPRK can give insight to the fragility of the economy or government of a country as they are needing to depend on NK and violate UN sanctions. Violating internationally mandated sanctions could result in unfavorable consequences for the country, disobeying the United Nation. It is also important to note how the country is involved with North Korea and if they are allowing NK to only do business, or also facilitating grounds for NK to have other proliferation activity.

Investigation Methodologies

The investigation on the topic of North Korean proliferation related activities in Africa will be done via a multifaceted research methodology, encompassing collection of information from diverse sources, by collecting information from reporting sources, research organizations, literature, economic data, and news reporting.

To provide a holistic perspective on the issue, review of reports and articles from a variety of sources, both academic and non- academic, will be done. Insights from the research findings and publications of reputable organizations and think tanks that specialize in the study of international relations, security, and proliferation will be particularly sought out. Furthermore, economic data will also be used to harness and discern patterns and relations between countries.

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is notorious for finding means for revenue to fund its military projects. The regime’s proliferation-related activities will be defined by activities that either contribute to North Korea’s generation of revenue, or is North Korea supporting military proliferation goals of an African country.

Proliferation Related Activities and Factors

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is notorious for finding means for revenue to fund its military projects. The regime’s proliferation-related activities will be defined by activities that either contribute to North Korea’s generation of revenue, or is North Korea supporting military proliferation goals of an African country.

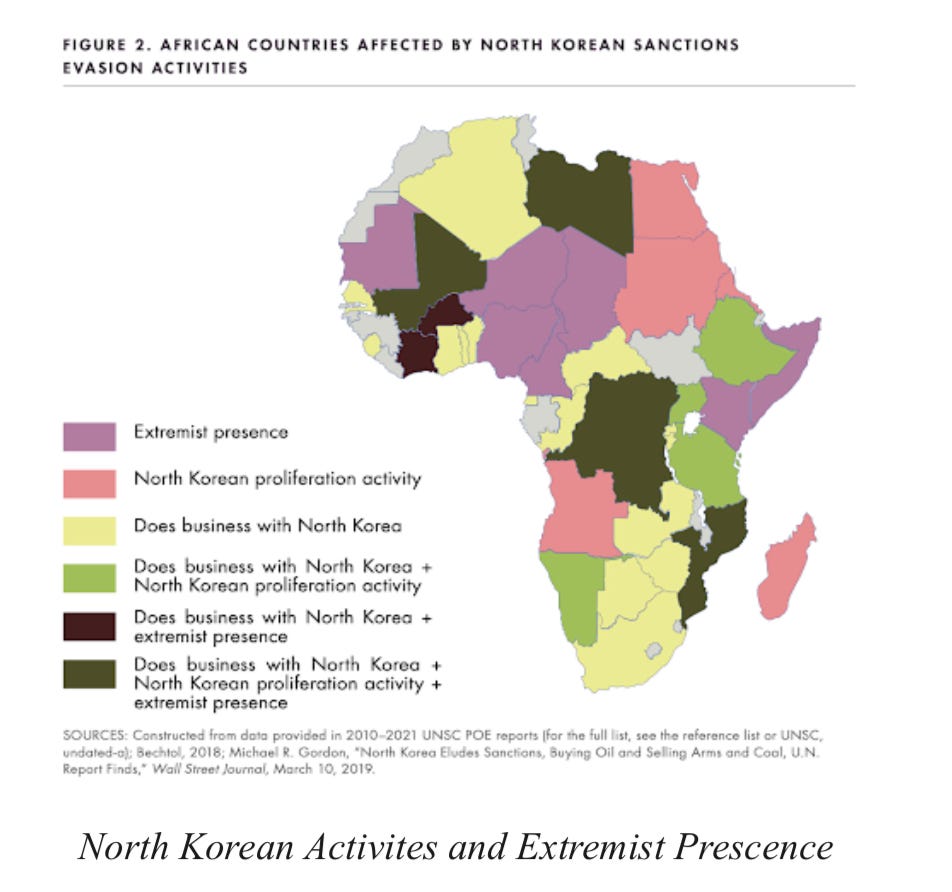

The figure titled “North Korean Activities and Extremist Presence” is from RAND Corporation, and it is a depiction of African nations, highlighting extremist presence, and North Korean business and proliferation activities.5 As seen in the figure, North Korea has relations with a significant number of countries, some of which are known to have extremist presence - a concern for stability and proliferation.

Exportation

According to the Observatory Economic Complexity, a data visualization site for international trade data, roughly 39%, the majority of North Korea’s exports went to Africa (about $73 million) in 2021. The largest acceptor of NK exports in Africa is Senegal, a customer for roughly 20.1% of total NK exports. Of the 20.1% of exports, 99.6% is of refined petroleum, amounting to $36.6 million USD. The amount of money recorded is not a lot in a general sense, however for the DPRK, a small amount of money goes a very long way.6 In addition to the number of sanctions, it is not easy for the nation to generate revenue via trade. There are a number of bans and restrictions on trade especially. UNSC Resolution 2375 is an example of how restricted the DPRK is in terms of exports and imports, as refined petroleum is banned for sale, supply, and transfer unless very specific conditions are met, and all textiles are banned.7As of the 2021 data, NK still exports textiles. The aforementioned resolution not only discusses trade bans, but also overseas work and sanctions on entities.

Revenue Generation

Categorizing revenue generation as a proliferation-related activity is due to how the funds earned by the North Korean government can be invested into the regime, military, nuclear programs, or whatever they wish to invest their income in. Plainly, a nation’s income is contributed by “goods and services produced for sale in the market and also includes some non-market production, such as defense or education services provided by the government,” defined by the by the International Monetary Fund.8 The DPRK generates income through various ways such as trade, selling arms, business through front companies and more.9 Furthermore, there are a number of shell companies and banks that contribute to North Korea’s revenue.

Evidence

Glocom

In a United Nations Security Council report for 2022, the Panel discussed information collected on Glocom, of the shell companies for DPRK’s pan Systems Pyongyang. Pan Systems Pyongyang, or Glocom, function under the Kim regime’s intelligence agency, the Reconnaissance General Bureau. The report mentioned how the front company continues to evade sanctions and purchases components for the sake of procuring military communications equipment for paramilitary organizations.10

It has been found that Eritrea has been having business relations with Glocom, or Pan Systems Pyongyang, and has been receiving “military radios and accessories.”11 In an article released on March 29 of 2023 from NKNews, it has been discovered that the Ethiopian military has been receiving shipments from the sanctioned company as recently as November of 2022. According to the article, two shipments of the DPRK communications equipment were delivered to the Ethiopian National Defense force.12

Mansudae Overseas Projects

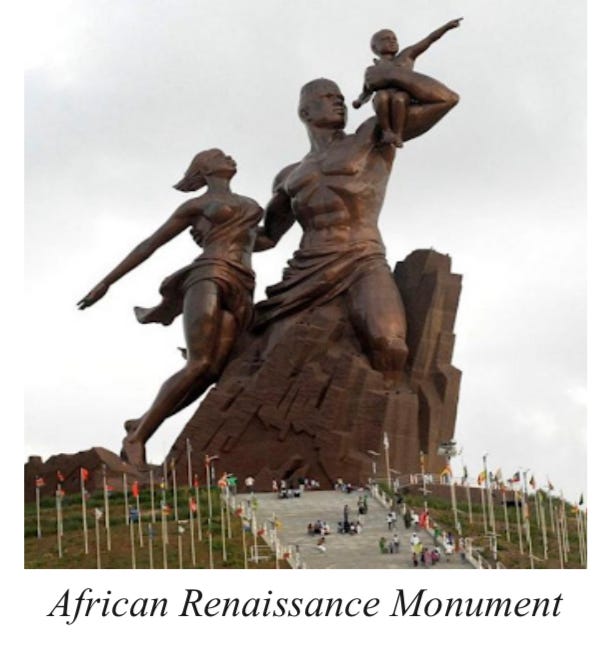

Mansudae Overseas Projects is an internationally serving DPRK construction company, a sub-company under Mansudae Art Studios, a sanctioned company. Thus far, at least 260 million dollars was generated through the years by Mansudae Overseas Projects, clearly a significant source of income revenue for the regime.13 There are a number of countries in Africa that have commissioned projects through this company: Zimbabwe, Madagascar, Mozambique, Namibia, Senegal, Mali, Equatorial Guinea, Angola, Benin, Botswana, and Democratic Republic of the Congo.14

The African Renaissance Monument (ARM), in Dakar, Senegal. The bronze monument is arguably one of Mansudae Overseas Projects’ more well known constructions. The ARM is of great value to Senegalese citizens as it conveys the people’s faith in improvement, an upwards trajectory of stability, strength, and power, and being free from “several centuries of imprisonment” on the African continent according to Former President Abdoulaye Wade.15 Despite the positive metaphor that the monument holds, the fact of the monument being built by North Korean workers resulte in some Korean worker distaste from the African population. In response to the disapproval, President Wade justified his choice of using DPRK workers rather than local works for the $27 million project because “they [the DPRK workers] were experts in constructing large public monuments.”16

Interestingly, North Korea’s construction company has been known to be often used for construction of government buildings. Namibia, in recent years, has faced disapproval from international countries for their relations with North Korea. They have collaborated with North Korea for developments and military projects such as making deals for “construction work for a military academy, a munitions factory, and military bases.” In addition to engaging with Mansudae Overseas Projects, Namibia also allegedly engaged with KOMID, a DPRK military arms company, by allowing them to operate under the arts/construction company; The Namibian Defense Force received arms from KOMID, likely alongside the military projects that Namibia used Mansudae Overseas Projects for.17

Military Arms

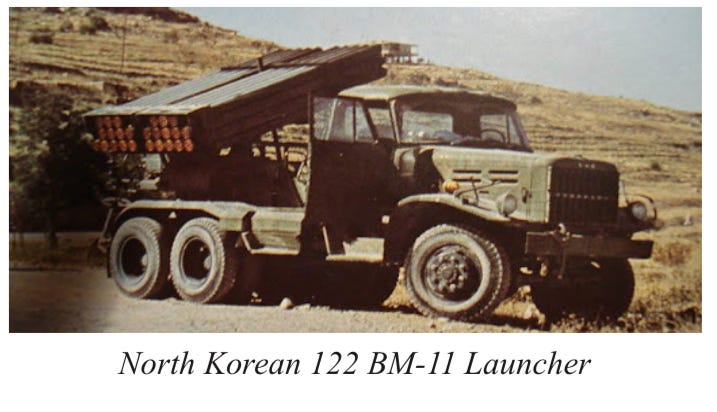

On April 26, 2023, an alleged weapon and conflict researcher under the handle “@war_ noir” on Twitter (or “X”), the social media platform, identified North Korean rocket launchers captured from Sudanese Forces. The Rapid Support Forces (RSF) posted a video of rocket launchers, three of which were “122 BM-11 launchers,” launchers to be originally from the DPRK.18 In the image with the Rapid Support Forces member, featured below, is a screen shot from the video that @war_noir is referring to, featuring an RSF member taking a video of the captured rocket launchers. The following image is a depiction of a 122 BM-11 launcher to compare to the vehicle in the video to confirm the model.

Upon watching the video from the RSF, the men appear to be boastful of their arms. They repeatedly chant, praising God, and say that victory is on them and that it is a victory for Sudan as they have tanks and armored vehicles. There is no mention of specifying the vehicles’ model nor where they originate, so it is likely that the RSF capturing the DPRK-made launchers was a coincidence, and not intentional. It should be noted that the translation of the video is merely partial due to incoherence and my lack of fluency of Sudanese Arabic.

In another recent case, a report found on NetAfrique, an African news reporting website based out of Cote d’Ivoire, disclosed news on May 15 of 2023 regarding the DPRK cooperating with the Malian junta to establish an ammunitions factory, just outside of Bamako, the capital of Mali. An excerpt of the report read, in French:

“Au mois de novembre de la même année, les Nord-coréens ont également rencontré de hauts responsables de la junte malienne pour échang- er sur le projet de construction de l’usine de mu- nitions dont le site est situé à Dialakorobou- gou, à une vingtaine de kilomètres de Bamako.”

Translation (done by myself):

“In November of the same year [2022], the North Koreans even met with senior officials of the Malian junta to discuss the project of ammunition factory construction where the site will be located at Dy- alakorobougou, twenty kilometers from Bamako.”

Furthermore in the same report, it was mentioned that a DPRK ambassador to Guinea in Conako, An Se-Oh, is in collaboration with the Minister of Territory Administration (le ministère de l’administration territoriale), Abdoulaye Maiga, and with the secretary general of the Malian Minister of Defense (le ministère de la défense), Brigadier General Sidiki Samaké (now Major General, according to other open source articles).19

Bamako, being the capital of Mali, could very well be a hub for collaboration of other international actors interested in working with the power transition that is ongoing in Mali, making it very convenient for the DPRK that the munitions factory will be in close proximity to the capital. It is especially of concern of North Korean collaboration with Mali due to the fragility of the government, terrorist activity, and the presence of Wagner. Consideration of the factors aforementioned, as well as the potential cooperation with the DPRK would be best when analyzing the diplomatic and political climate in Mali, and surrounding areas.

Medical Workers

As mentioned prior, the DPRK regime often uses the exportation of labor and other services to other countries in order to gain revenue. Apart from construction, a common service for African countries to look for from North Korea are relating to medicine. Based on recent United Nations reports, there are a number of cases where DPRK medical doctors and medical workers are working in Africa, not abiding by the UN sanctions. Côte d’Ivoire, Togo, Mozambique, and Senegal are some of the countries that were mentioned in UN reports for hosting DPRK workers.

In Côte d’Ivoire, medical doctors from the North Korean entity, Korea Moranbong Medical Cooperation Center, work in various medical centers within the country. It is unknown if the North Korean workers that are in the other African countries are from the same entity. The DPRK medical workers in Togo were allegedly invited by Evangelical churches to be employed by various Togo entities. Both cases, in Côte d’Ivoire and Togo, were disclosed in September of 2022.

20A more recent UN Report from September of 2023, mentioned medical workers from Mozambique and Senegal. As of December 2022, two Mozambique hospitals were facilitating three medical workers from the DPRK. In response to the violation, Mozambique replied with acknowledgement, but justified the employment by saying that they needed these “qualified” and “specialized” workers to aid with the demand for doctors needed by the National Health Service. In a similar effort to satisfy the need for doctors, an unnamed non-government organization in Senegal were found to be working with a medical team, introduced by a DPRK ambassador, of around 30 North Korean medical professionals.21

It is interesting to see Africa working particularly with North Korea for needed labor and workers rather than outsourcing personnel from countries that are closer. North Korea’s medical diplomacy raises questions of why African nations resort to the DPRK. It is likely that the cost of NK workers is cheap and the need for workers is dire enough to disregard the UN sanctions. On Kim’s regime side of things, why does the hermit country send all of these medical doctors overseas while its own citizens are having numerous health problems? Medical personnel are thoroughly trained and educated in the DPRK, however there is a gap between the number of medical workers and necessary sources for treatment. Thus, the situation creates an opportunity for the government to bring in resources and proper necessities for treatments, or send off excess doctors. Sending off excess doctors would bring in revenue for the sanction-illed country.22

Diplomatic Cover

Diplomatic immunity is a concept that the Kim Regime takes advantage of. The immunity protects the designated diplomatic location, “missions,” and diplomatic personnel from being searched, arrested, and prosecuted. However, the home country of the diplomat could revoke immunity, and have the diplomat be prosecuted.23

North Korea has benefited greatly from diplomatic immunity as they have embassies all over the world, especially in Africa. They have used the grounds and workers of their embassy in order to cultivate revenue for its government. There are a few ways that the DPRK has used to generate revenue through means with diplomatic covers, however two ways that seem to be common would be either having a business where the “mission” is located, or using diplomats to bring back hard cash to their home country.24

A recent example of using diplomatic cover for sanction evasion is how the North Korea Foreign Trade Bank functioned while using a diplomatic cover in Tripoli, Libya. In the neighboring country of Tunisia, a representative from the bank opened accounts at the Arab Tunisian Bank and International Arab Bank of Tunisia for reasons that support the DPRK’s proliferation activities. This particular event was reported by the UNSC in 2018.25

Counterfeit Money

For an example of sanction evasion, a method of NK generating cash is converting counterfeit USD through a middleman, and depositing the exchanged funds into a bank account.26 This method is known to be often used in China, however this method has also been found to be used by the DPRK in Africa as well. In an interview by JavaFilms, a documentary and film company, with Ko Young-hwan, a former North Korean diplomat for African nations, he discussed instances of these operations of generating income to send to North Korea while using foreign exchange and counterfeit money during his time at Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. The method that they used was slightly different: they would have counterfeit $100 USD bills printed and be hidden throughout a stack of cash amounted to $10,000. They would then exchange the cash, with fake and real bills, into the local currency, Congolese Franc, at a local bank. After receiving the cash in Congolese Franc, they would then exchange the cash again at a different bank to USD, thus resulting with thousands upon thousands of USD readily available to be used at Kim Jong-un’s dispense.27

Analysis

Given the various ways that the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is and has been entangled within Africa, it is evident that it is imperative for the enforcement of UN sanctions and bans. Improvement on enforcement would be necessary to effectively curb North Korea from generating revenue to fund Kim Jong-un’s military projects, to have better predictability of warfare/military capabilities of nations or non-state actors, and to encourage more ethical sources for labor. The ramifications between Africa and North Korea extend beyond creating the possibility of a more powerful and armed DPRK; there is also an increased risk of instability and threat in fragile African nations. The presence of extremist terrorists, paramilitary groups, and coup forces are all potentially able to get a hold of any military arms or ammunition that the DPRK has provided to these nations’ military/ government entities. As seen in the case of the Rapid Support Forces of Khartoum, Sudan, a non-state actor was able to seize the arms. Could there be a possibility for terrorists to gain DPRK arms? In the aforementioned news report regarding the Mali-North Korean collaboration for the munitions factory, there is a potential for Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) to take advantage. The location of the potential factory, in Dyalakorobougou, Mali, there is no JNIM presence, however JNIM is active not too far north of the city.28

Additionally, the fact that exports to Africa has exceeded exports to Asia, as of 2021, is of great interest. Not only is it alarming to see such a relationship, but especially so when paired with the knowledge of sanction evasion activity in Africa. It begs the question of whether the reported exports are truly what is being traded and what sanctions are being evaded through trade currently. It is crucial to acknowledge the potentials for risk and to safeguard stability in the region. Additionally, it is especially to the US advantage to be wary of Africa’s vulnerabilities and who is taking care of them, as China and Russia have been gaining influence in the region. The degree of anti-west sentiments could very well possibly increase as North Korea gains more of a presence in Africa alongside China and Russia. The history between the DPRK and Africa only bolsters their relationship. Increase in relations between Africa and China, Russia, and North Korea could potentially drive Africa to be more dependent on those countries for aid, technology, resources, educational aid, etc.

Thus, as discussed and shown, there are various aspects to the DPRK’s involvement in Africa that are, and could be, not only ethical issues, but also strategic issues on an international degree.

Sovereignty at Stake: The Impact of Chinese and Russian Influence on Remote Communities in the Sahel

Henry Leverett

Concerns and Considerations

The Sahel region of Africa, which includes Mauritania and Mali, is facing a growing security threat from China and Russia. Chinese and Russian involvement has been perceived as a beacon of progress and development, eagerly embraced by African governments.1 This enthusiasm is partly driven by the immediate benefits of infrastructure projects and military funding/ training provided under the auspices of China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Wagner’s expansion across the continent.2 For African leaders, these projects are not just infrastructural enhancements; they are tangible symbols of progress and change, potentially swaying public opinion in their favor during elections.

However, this short-term gain masks a more insidious long-term strategy. By engaging in these partnerships, African nations find themselves entangled in contracts and agreements that span decades, granting China or Russia extensive rights over mining and extractive resources. This not only exploits the continent’s rich natural resources and cheap labor but also strategically positions China to counter Western-based aid and education programs. The allure of immediate aid and development overshadows the potential for long-term dependency and exploitation, leading to a new form of neocolonialism. As China and Russia strengthen their geopolitical foothold, these African nations risk losing their sovereignty and becoming pawns in a larger game of international power dynamics.3

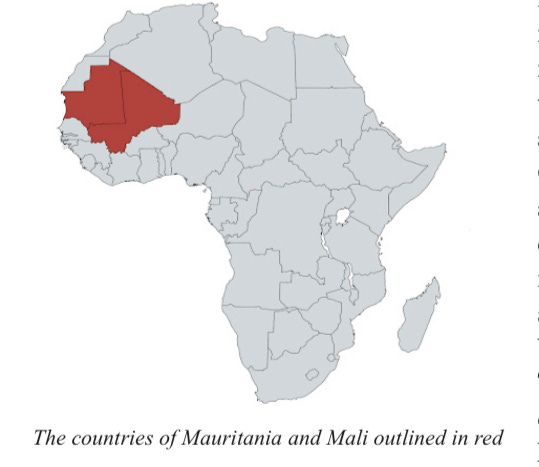

Mali and Mauritania present compelling case studies for understanding the susceptibility of African nations, regardless of their political alignments, to the influence of China and Russia. Mali, grappling with a corrupt government, terrorist activities, and frequent coups, demonstrates how internal vulnerabilities can open doors for external powers like China and Russia to assert their influence. Conversely, Mauritania, traditionally Western-aligned, shows that even nations with established international alliances are not immune to the persuasive tactics of these global powers. These contrasting scenarios in Mali and Mauritania underscore the nuanced ways in which both China and Russia can extend their geopolitical reach across different African contexts.

China’s Role in Mauritania and Mali

China’s economic engagement in Mauritania and Mali includes significant infrastructure projects and investments in the mining sector. In Mauritania, China has been involved in building roads, bridges, and hospitals through the Belt and Road Initiative, with a notable debt relief package of $21 million granted to the Mauritanian government.4 In Mali, Chinese investment includes a $112 million deal by Hainan Mining, a subsidiary of Fosun International Limited, for a majority stake in a lithium mine, signaling a significant interest in Mali’s mineral resources.5 Furthermore, China’s engagement in Mali also encompasses various development projects like the construction of the Center of Vocation Training in Senou, the University Campus of Kabala, and the agriculture demonstration center in Baguineda.

In addition to its economic engagement, China has also increased its military cooperation with Mauritania and Mali. In 2021, China provided military aid to Mali, including armored vehicles and weapons. China has also trained Malian troops and provided intelligence support. This support, articulated by China’s deputy permanent representative to the United Nations, Dai Bing, and Zhang Jun, also extends to funding, equipment, and logistics. In the same year, China significantly increased its military cooperation with Mali by providing nearly 100 armored vehicles, including VP11 armored vehicles and Lynx CS/VP11 off- road vehicles.6 This military aid was aimed at enhancing Mali’s capabilities to address various security challenges, including terrorism, ethnic conflicts, and political instability, which have been prevalent in its northern and central regions.6

China’s propaganda campaigns in Mauritania and Mali are also on the rise.7 The Communist Party of China (CPC) controls numerous media outlets that produce content that is distributed through email to various smaller African news agencies for very low or no cost. In many cases, the African news agencies will disseminate this free and expertly written content as their own. In almost all examples, there is an anti-west and pro-China spin on the content which amplifies their messaging under the guise of grassroots legitimacy. Additionally, Chinese propagandists are creating a substantial amount of “soft” content for African audiences, which is disseminated to urban elites and youth via streaming services, social media, and phone apps.

Russia’s Role in Mauritania and Mali

Russia’s influence in Mauritania and Mali is also growing. In 2021, Russia deployed mercenaries from the Wagner Group to Mali to help the government fight against Islamist insurgents. The Wagner Group has been accused of human rights abuses since their arrival in Mali in December of 2022. Human Rights Watch reported that these forces, alongside the Malian army, summarily executed and forcibly disappeared civilians, and allegedly tortured detainees.8

Russia has also been providing military aid to Mauritania. In a significant demonstration of their growing military cooperation, Russia stepped up its support for Mauritania in 2022 by donating a substantial package of military equipment, including several helicopters and armored vehicles.9 This move was widely seen as a strategic decision by Russia to bolster its presence in the Sahel region and counter the growing influence of Western powers, particularly France, in the area. The donated helicopters included three Mi-8MT multirole transport helicopters and two Mi-25 attack helicopters. The Mi-8MT helicopters, with their large cargo capacity, would prove invaluable for transporting troops and equipment to remote areas, while the Mi-25 attack helicopters would provide a powerful deterrent against armed groups.

On 9 August 2022, officials received one Su-25 jet, four L-39 jet trainers, a Mi-24P attack helicopter, a Mi-8 transport helicopter, and a single Airbus C295 tactical transport aircraft. The C295 aircraft arrived on 31 May and is the second to be acquired, with the first delivered in December 2016. Two Mi-24Ps were delivered to Mali on 30 March 2022, along with Protivnik-GE/59N6- TE mobile radars from Russia. Mali also recently acquired four Mi-35s from Russia. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s arms transfers database, Mali in 2020 ordered four Mi-8MT/Mi-17Sh helicopters from Russia for $61 million including training and weapons, with deliveries from 2021. The Su-25s and L-39s appear to be new acquisitions as well.10

In addition to the helicopters, Russia also donated a number of armored vehicles, including several BTR-80A armored personnel carriers (APCs) and BRDM-2 reconnaissance vehicles. The BTR-80A APCs, with their thick armor and powerful armament, would provide a robust means of transporting troops into combat zones while the BRDM-2 reconnaissance vehicles would allow Mauritanian forces to scout ahead and identify potential threats.10

Russia’s engagement in training Mauritanian troops is part of a broader strategy to enhance its military cooperation and influence in Africa. In June 2021, Mauritania, , which collaborates closely with France and the US, signed a military agreement with Moscow. This agreement represents a strategic move for Russia to expand its influence in Mauritania, a key country connecting the Maghreb region with West African countries.11

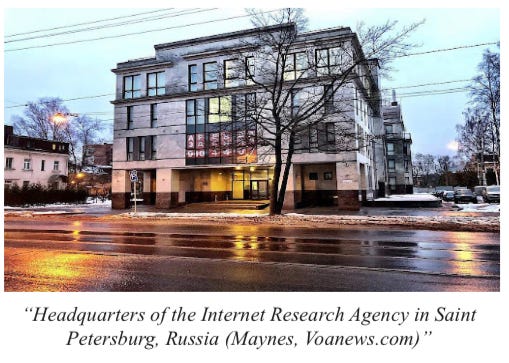

Russia’s propaganda campaigns in Mauritania and Mali are also becoming more sophisticated. Russian media outlets are promoting a narrative that the West is responsible for the region’s problems, while Russia is the only country that can help. Russia is also funding social media campaigns to spread disinformation and sow discord in the region. The most notable example of this comes from the Internet Research Agency (IRA), founded by

Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Russian oligarch with close ties to the Kremlin, has been a key player in Russia’s sophisticated propaganda campaigns in Africa. This notorious troll farm, sanctioned by the US government for its role in interfering in American elections, has been actively involved in spreading disinformation and influencing public opinion in various African countries.12

In Mauritania and Mali, the IRA’s tactics have evolved to include the creation and management of numerous fake online personas and social media accounts. These accounts pose as legitimate local entities, such as grassroots organizations and interest groups, to disseminate narratives favorable to Russian interests while undermining Western influence.12 The IRA’s operations are not just limited to social media; they also extend to organizing and coordinating political rallies and other activities to deepen divisions and sow discord.

Moreover, the IRA’s activities in Africa are part of a broader strategy by Russian-linked organizations, including the Wagner Group, to expand their influence across the continent. These operations are characterized by a mix of state-sponsored propaganda and private interests, often blurring the lines between official Russian policy and the activities of entities like the IRA and Wagner Group.13 The IRA’s involvement in Africa highlights the complex and multifaceted nature of modern information warfare, where state actors and private entities collaborate to achieve geopolitical objectives.

The Impact of Chinese and Russian Influence on Regional Security