INSIDE

Keeping the Music Alive on a Half-Open Island

Between Fact & Fiction: The Historiography of the Maronite Church

An Analysis of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam

International Human Rights and the United Nations: A Case Study of the Rwandan Genocide

The Terrorist Identity and How it Develops

Table of Contents

Letter from the Editor

Keeping the Music Alive on a Half-Open Island

Between Fact and Fiction: The Historiography of the Maronite Church

An Analysis of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam

International Human Rights and the United Nations: A Case Study of the Rwandan Genocide

The Terrorist Identity and How it Develops

Authors Biographies

Works Cited

Letter from the Editor

When I joined Alger in the Fall of 2021, I never imagined I would be the Editor-in-Chief for the 2023 edition. I instantly felt at home with the people of Alger, and the interest in expanding my writing skills reignited my love for writing. When planning this year’s publication, Isabelle, Rachel, and I aimed to recruit more members and grow the organization. We achieved this goal in more ways than one. Alger hosted guest speakers working in journalism, watched a documentary, and discussed many journalistic topics and current events. I am most proud of the connections and friendships formed among our members this year, as seen in the peer-written biographies. I enjoyed learning about and reading everyone’s interests in international affairs and seeing them turn into articles.

The 2023 publication features a range of broad and niche topics in international affairs. The writers explored intriguing topics that challenged them in a variety of ways. Every article is unique, ranging from field research to international law.

It was an honor to be Alger Magazine’s Editor-in-Chief and work with a fantastic team. From our continent articles to after-meeting chats, Alger has created some of the best memories I will take from Ohio State. Thank you to our writers for their well-written articles and everyone who attended the meetings. Thank you to the managing editors for their hard work and support. I hope the readers enjoy this edition and I look forward to next years publication.

Sincerely,

Angela Heaney

Editor-in-Chief

Keeping the Music Alive on a Half-Open Island

Hayden Bidinger

I spent July 2021 in a place where I never expected to; in a small nation, on an even smaller island in the middle of the ocean. I guess it was less surprising to the people close to me because they associate anthropology with scholars traveling to remote regions of the world. I ended up in Malta as one of the first steps as a fledgling anthropologist when I signed up for an ethnographic field school that teaches the basics of conducting sociocultural research in the field. The field school was located on the country’s second-largest island Gozo, which is in constant contact with Malta proper. As a plucky but nervous sophomore anthropologist, I managed to fly and ferry my way to this small, complex, and culturally rich “heart of the Mediterranean” during the middle of the global COVID-19 pandemic.

Imagine the Italian peninsula, the boot, and its soccer ball that is Sicily. South of Sicily lies three islands, each smaller than the last, the Republic of Malta. Aside from the many islets that dot the waters of the archipelago, there is the largest island, Malta, which shares the name of the whole nation, its little sister Gozo, and finally, Comino. The island of Comino has only two permanent inhabitants and functions mostly as a bird sanctuary, a nature reserve, and a popular day-drinking lagoon for tourists. Gozo is home to a considerably larger number of people, around 31,000 (National Statistics Center, 2021). The island is built upon its dry hills that roll and separate its many small villages, with the capital of Victoria/Ir-Rabat being its largest “city” of around 6,400 Gozitans. Finally, there is the mighty Malta proper,with a population of around 400,000. Most people living in Malta reside within the metropolitan area of the country’s capital and largest city, Valletta (Eurostat Database, 2022).

From an anthropological perspective, the culture and subcultures that have developed on the Maltesearchipelago make for an interesting study due to its uniqueness and the clear influences it draws from other cultures. Many influences come from its history, a small part in the story of many great empires. To name a few, the Phoenicians, Romans, Aglahbids, Normans, Napoleon, and finally, the British all claimed and influenced the islands before becoming an independent republic in 1974 (OSP Productions, 2019).

The Maltese speak a Semitic language with loan words from Italian, French, and English, use a modified Latin alphabet, and are a majority Roman Catholic nation, but many place names come from Arabic (Baldacchino, 2011). Many towns have vibrant nightlife,and the country was divided by who supported England and Italy during the 2021 European Football Championship (Bidinger,2021). Malta is not a melting pot or a salad like so many people describe nations like the United States, but rather I see Malta more as a well-ornamented house. The foundation is old and firmly Mediterranean, with stones that are Greek or Roman in origin. Yet, this imaginary house has a traditional Arabic courtyard with French-style windows. The furniture is British, but the decor is Italian. The kitchen is stocked with ricotta, macaroni, date-stuffed pastries, blood sausages, and rabbit stew. Walking through the house, you can take your time to point out examples of what comes from where but before you leave, it somehow manages to feel Maltese. Each villagehas its own traditions, dishes, and patron saint.I admit to being rather overwhelmed when I first began to experience Maltese culture for the first time because I did not have the faintest clue of where to start looking for ethnographic research.

Ethnography is a type of sociocultural research within the broader discipline of anthropology, which systematically studies a particular culture, phenomenon, tradition, or people using scientific description. Theory and methodology vary widely among ethnographers. This can range from using complex models in predicting agricultural output to using detailed, subjective descriptions to understand the perspectives of research participants and the researcher themselves. One of the most critical tools of an ethnographic researcher is participant observation, or the practice of actively engaging in cultural activities. The ethnographic researcher develops a deeper scientific understanding of the subject matter and acknowledges the cultural relativity of being an observer. (Bidinger, 2021).

Off the Beaten Track is the field school I participated in, which teaches individuals interested in anthropological research how to engage in field-work and is based in the town of Xlendi on the island of Gozo. They encouraged us to develop our own research topic and thesis. We were left mostly to our own devices but had dinner every night with our hosts, where we discussed our ideas and the work we had conducted for the day and were provided ample advice.

Upon arriving in Gozo, I became interested in what kind of music they play at live venues and how these places had adapted to COVID-19. My fellow participant, Francesca, and I stumbled upon Zeppi’s Pub in the town of Qala. The pub hosted a recording session for the band All Snow, No Alps that day. After looking further into Gozo’s pop music scene, I decided to focus my research on the live music environment found in Gozitan pubs in the world that existed from the ebb and flow of COVID-19 regulations.

I began my research by traveling around the island, seeking venues that hosted local live music. Once I ascertained where people went to listen to live music and experience a community setting, I placed myself in the environment. This was done through simple tactics like Google searches and asking pub and café owners if they hosted music nights. I interviewed musicians, employees, and bar owners while also participating with people involved in these communities. The interviews I conducted were rather casual, to the point where I tried to strike up conversation with strangers. Later, I would write down important information and reflections on these conversations, but I was not afraid to take notes if I thought there was any chance of forgetting or misremembering. Similarly, I conversed with the people who attended the shows and reported being frequent patrons. My priority, however, was musicians. Business owners, staff, and fellow patrons were also interviewed to develop a fuller picture of the scene.

From these interviews and conversations, I learned how essential the presence of live music and the Gozitan pub scene is to the island’s social life. These pubs serve as light-hearted meeting halls for community members of all ages to gather and fortify the bonds that make them a community. An analogy for the importance of live music venues to Gozitan communities can be seen in the geographical location of Zeppi’s. The pub, which has a small interior with not much more than a bar and a restroom but with ample seating at tables in the courtyard, sits directly next to the St. Joseph Parish Church. From the courtyard of Zeppi’s, patrons can glance to see the massive, baroque facade of one of the institutions that unite a village. When the town of Qala wakes up on Sunday morning, many residents congregate and communicate at St. Joseph, then in the evening, they come together again at Zeppi’s. Zeppi’s itself almost acts like a secondary church where individuals form a broader village community. Cafes and pubs become part of weekly routines. There are the same faces and perform the same rituals, just like Mass, yet there is also variation in topics of sermon or conversation. Most importantly, it is a third place outside of work or the home where individuals and families interact with their neighbors.

Community gatherings were hit hard by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. The Maltese government implemented many policies similar to those in the United States and other nations in response to the viral outbreak (Bidinger,2021). Travel was heavily restricted, and it was only after a year of COVID-19 that I was able to participate in the field school. Public gatherings were heavilty dissuaded, restricted, and in some cases prohibited, while social distancing, masks, and sanitization were highly encouraged. The pandemic made it incredibly difficult for Gozitans to worship in their holy spaces and almost impossible for institutions like Zeppi’s to host live performances. By July 2021 in Gozo, many efforts were beingmade to return to normal life, but many venues on the island had suspended hosting performances or closed down entirely. Pubs and cafes bravely navigated the restrictions set in place to prevent the spread of COVID while maintaining the atmosphere of their music nights. Masks were required to order or use the restroom inside. Once seated outside, patrons were free to remove their masks and talk to the people at their table. The tables were arranged every afternoon to comply with social distancing requirements. I spoke with the owner of Zeppi’s about how she was adjusting her business strategies to COVID-19 restrictions. She was willing to do whatever she could to keep her doors open, musicians playing, and the community together. The same could be said for the musicians that played at Zeppi’s. They were itching to get back to playing in front of living people instead of alone in their homes or in front of an emotionless screen. Not only did the pub host local and Gozitan musicians, but bands would come from Valletta to play for any crowd of any size.

This was the general attitude of the patrons,employees, and musicians at pubs across Gozo. After more than a year in quarantine, they were simply happy to be back to the locations they loved. They missed their friends and family, who would sit together for a couple of drinks outside their local music venue. The musicians not only needed the income to help support their families, but a couple of bands I spoke to had been together longer than I have been on Earth. Their bandmates were their siblings and friends with whom they had been unable to jam for almost a year.

One interview stuck with me early in my research. I interviewed a man from Wales who had a long line of Gozitan ancestry. I learned about the history of Qala, the musicians at Zeppi’s, and he helped me overcome my initial jitters of conducting interviews with complete strangers. He told me he was a Buttigieg and that his grandfather came from Qala, as did the Buttigieg surname itself (Bidinger, 2021).

Aside from politics, we spoke about our lives. He asked me about my research and why I had ended up in Gozo, why I was choosing to study music venues, and about my dreams and ambitions for when I returned to the United States. From the natural flow of the conversation, I learned that he would soon be leaving his home in London for the U.S. and therefore decided to vacation in Qala one last time. His family would stay in Gozo during their summer vacation since he was a little kid to visit his grandfather, who had recently passed. Now he came by himself to experience, if only for a fleeting second, part of his childhood and the community with which he and his ancestors were familiar. He said there’s no better place to do that than music night at Zeppi’s. This conversation allowed me to better understand the community I was researching and proved that I could be onto something truly amazing about how live music played a role in Gozo.

By reopening the venues, even in a limited form, we can glean insight into how important the live music scene is to the people of Gozo. Despite the risk, it is their way to share a space with their neighbors. The venues serve a critical function in creating an open place where a village could unite in a common activity, even if only for a couple of hours in the evening. Without live music and other community settings, the heartbeat of the towns and villages of Gozo beats fainter. Without the music, when the sun sets, the streets are quiet and empty. Without the cafes and pubs, thee is no place where old friends could share a meal or a few drinks. It makes sense that the attitude was a relentless adaption in order to preserve every element that keeps their community connected.

It was beautiful to see this determination and people coming together. The July evening in Gozo comes after blisteringly hot days when a cold drink is much needed and desired. I would show up early to the venues to take some observational notes, but by the time the band started to play, it was like being transported to a whole different world. During the day, the sun is inescapable and everyone is busy with their jobs and the stress of life.

With the breeze finally blowing cool, the gleaming street lamps and bar lights, and being surrounded by families, coworkers, friends, and tourists. We were united by our appreciation and dedication to the melodies played, even if for a fleeting second, something close to what it means to be a part of their community that they were fighting to keep together.

Between Fact and Fiction: A Historiography of the Maronite Church

Michael Sarkis

The Maronite Church is part of the Eastern Rite of the Catholic Church, utilizing the West Syriac Liturgy. The Patriarch of Antioch and all the East is its head, residing in Bikirkī, Lebanon (“Maronite church”). In Lebanon, Maronites make up at least 20% of the population, but there are more than 3.4 million Maronites worldwide (Henley 89). One interesting thing about the Maronite Church is the heavy debate surrounding its early history. Maronite historians argue that the Maronite Church has been in perpetual unity with Rome since its inception, while the critics of this narrative argue that the Maronites were initially Monothelites who later joined the Catholic Church. This article will examine this debate surrounding the early history of the Maronite Church up to the Crusades.

There are few Maronite documents before the 17th century, but they do not focus on the history of the Maronite Church. However, works chronicling the history of the Maronite Church have emerged since then. These works emerged, as Kamal Salibi describes, from “a predominantly clerical tradition, with the defence of perpetual orthodoxy of the community as an outstanding feature” (17-18). In this context, perpetual orthodoxy refers to the claim that the Maronite Church has, since its inception, been in communion with the Roman Catholic Church, and the Maronites have been determined to refute all accusations to the contrary (Salibi 15-16). This defense of perpetual orthodoxy can be seen in the works of Reverend Burtos Dau and Father Walid Peter Tayah. end Burtos Dau and Father Walid Peter Tayah.

Both Tayah and Dau posit the beginning of the Maronite Church with the life and deeds of Saint Maron, citing Theodoret of Cyrrhus’s Religious History to attest to his existence. St. Maron lived between the fourth and fifth centuries in the southern Turkish province of Kylikia (Tayah 18). According to Dau, St. John Chrysostom wrote to St. Maron in either 404 or 405 CE (162). Theodoret narrates the life and deeds of St. Maron and, according to Dau, states, “that St. Maron was the founder and master of the monastic life in the province of Cyrrhus, and that many heroes of the monastic life were trained by St. Maron...” (164). When St. Maron died, villagers in the surrounding village seized his remains, taking them to “a locality south of Cyr where, after solemn burial rites, a church will be erected on his tomb” (Tayah 23). As noted by Tayah, Pope Clement XII and Pope Benedict XIV upheld the sainthood of St. Maron (26).

Following the death of St. Maron, the Council of Chalcedon was convened by the Emperor Marcian of the Roman Empire in 451 CE to end the dispute surrounding the two natures of Jesus Christ and how the doctrine of the Incarnation should be phrased (Denova). The Council concluded that the two natures of Christ remained distinct but unified (Denova). However, the Council also condemned Monophysitism, the belief that Christ had one nature, leading to a schism between the supporters of the Council and those who upheld Monophysitism, such as the Coptic Orthodox Church and the Syriac Orthodox Church (Denova; “Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East”). The Chalcedonians would later separate into the Catholic Church and Orthodox Church in 1054 (Denova). Maronite historians argue that the Maronite Church sided with the Council of Chalcedonian and cite the Letter of the Monks of Syria Secunda to Pope Hormisdas as evidence.

Following the Council of Chalcedon, the Arab historian Abu-al-Fida writes that Emperor Marcian erected the Monastery of St. Maron in 452 AD in modern-day Homs (Naaman 1). According to Tayah, this monastery “became the mother ... of the Maronite Church” and would “become the head of a powerful monastic confederation grouping dozens of monasteries in Syria and in Lebanon” (Tayah 29). As evidence of the Monastery of St. Maron’s leadership and adherence to the Council of Chalcedon, Maronite historians, once again, cite the Letter of the Monks of Syria Secunda to Pope Hormisdas as evidence.

In this letter, written in 517 AD, the Chalcedonian monks of Syria Secunda are writing to Pope Hormisdas to “reveal ... what persecution we have suffered... on the part of Severus (Patriarch of Antioch) and Peter (Bishop of Apamea)... for the purpose of compelling us to reject the Chalcedonian Council...” (Dau 173). The monks write that when they were traveling “towards St. Simon’s Monastery... we were attacked by wicked persons who killed 350 of us and injured as many” (Daw 173). The Maronite Church claims that all 350 slain monks were Maronites and commemorates them on July 31st (Azize).

The letter is signed by “Alexander, Priest, Superior of the St. Maron Monastery” and “followed by the signatures of twenty-five superiors of other convents and of one hundred and eighty-five prelates, priests and deacons” (Dau 175, 180). Reverend Dau interprets this letter as demonstrating that the Monastery of Maron “was the center of a coalition of a large number of monasteries in the fifth, sixth, and seventh centuries” and the adherence of the Maronites to the Pope as the “universal authority over the whole Christian Church” (179-180).

Following the Byzantine defeat at the Battle of Yarmouk in 636 CE, the Rashidun Caliphate swept through the Levant and conquered modern-day Syria, Jordan, and Palestine (Khan). Following the Islamic Conquest of the Levant, according to Tayah, the Byzantines bankrolled the Mardaites, otherwise known as the Marada or the Jarajima, to harass the Caliphate in the 7th century (42). According to Dau, the Mardaites were able to conquer all of Mount Lebanon and the mountain range from the mountain of al-Lukam to Jerusalem (Dau 213). Regarding the origins of the Jarajimah, Tayah and Daw disagree on their ethnic origin. Tayah claims that they were one of the various peoples fleeing the Byzantine-Arab wars who settled in Lebanon and the mountains of Amanus (Tayeh 42 check). According to Daw, “The Jarajimah-Maradah were originally a Lebano-Syrian people, the Amorites of the Bible,” with some Mardaites living in Asia Minor and Armenia (211-212).1 However, both agree that the Mardaites were part of the military wing of the Maronites (Dau 213; Tayah 42).Daw maintains that the Mardaites were so successful that they were able to sign treaties with the Caliphs that recognized the independence of the Maronites (Daw 192).

However, a treaty was signed between the Caliph Abd-al-Malik and Emperor Justinian II to withdraw the Mardaites attached to the Byzantine army in Lebanon, but the bulk of the Maronite forces continued to remain in Lebanon (Dau 216). When the Maronites resisted this attempt to disband the Mardaites, the Byzantines attempted to crush Maronite independence but failed (Dau 216). During this time, John Maron was elected as the first Maronite Patriarch to the Patriarchate of Antioch in 685-686 CE, following the death of the Patriarch Theophanus in 686 CE (Dau 214-215).

John Maron was born in the village of Sarum in Antioch to a French prince who had immigrated to Antioch (Dau 207). Before he was elected Patriarch, John Maron was a monk of the Monastery of Maron and Bishop of Batrun, who worked tirelessly to convert the people of Lebanon to Catholicism (Dau 208). Daw also credits John Maron with being responsible for organizing the Mardaites into a military force to defend Lebanon, with Mardaites from Asia Minor and Armenia flocking to join them (Dau 212-213). His feast day is celebrated every year on March 2nd (St. John Maron Feast Day.”).

Not much is known between this period and the next major flashpoint in Maronite history came in 1099; the Crusaders reached Lebanon and were welcomed by the Maronites. In 1182, William of Tyre claimed that 40,000 Maronites volunteered to fight with the Crusaders and entered into union with the Roman Catholic Church (Abouzayd 737; “Maronite church”). However, Tayah takes aim at Tyre’s assertion that the Maronites had converted to Catholicism, asserting that this was more of a reunion and that there would be other misidentified conversions of the Maronites to Catholicism (60-61).

This clerical historiography has suffered from intense criticism from non-clerical and non-Maronite scholars who take aim at the claim that the Maronites have been in perpetual union with the Roman Catholic Church and this narrative of the early history of the Maronite Church. Two important scholars who have leveled these claims are Matti Moosa and Mouannes Hojairi.

“John Maron... responsible for

organizing the Mardaites into a

military force to defend

Lebanon, with Mardaites from

Asia Minor and Armenia

flocking to join them.”

(Dau 212-213).

First, Moosa attacked the claim that Emperor Marcian built the Monastery of Maron. Both Tayah and Dau cite Abu al-Fida to argue this claim, but Moosa demonstrates that Abu al-Fida’s claim is questionable. Firstly, Abu al-Fida’s source is not first-hand but is derived from Abu Isa Ahmad Ibn Ali al-Munajjim’s Kitab al-Bayan’ an Tarikh Sinii Zaman al-’Alam ‘ala Sabil al-Hujja wa al-Burhan, and outside of Abu al-Fida, no other source has claimed that Emperor Marcian built the Monastery of Maron (Moosa 28-29). Aside from this lack of corroborating sources, Moosa points out that Abu al-Fida’s claim contradicts the theory of Maronites, such as the Patriarch Istephan al-Duwayhi, that “the inhabitants of ‘Hims and Hama’ had built this monastery” (Moosa 29). Even if the claim that Emperor Marcian constructed the Monastery of Maron is true, there is no reason to believe that this Monastery is the one that the Maronites descended from and that it was named after St. Maron. Moosa writes that the Patriarch al-Duwayhi noted that there were several monasteries with the same name, such as in Constantinople and Damascus, and that there were even multiple Monasteries of Marun in the vicinity of Hama (25-26). As a result, it is difficult to assert the reliability of this source that both Dau and Tayah utilize.

Next, Moosa challenges the argument for perpetual union formulated by Dau and Tayah. He draws suspicion from the Letter of the Monks of Syria Secunda to Pope Hormisdas. First and foremost, Moosa notes that no other signatory than Father Alexander “is identified by his monastery” (74). Aside from this, Father Alexander does not write which Monastery of Maron he is from, and as a result, “we are left to conjecture whether he was the abbot of the monastery which contemporary Maronites maintain to be the only monastery by this name in Syria Secunda” (74). The reader should be reminded that Dau uses this letter to argue that the Monastery of Maron “was the center of a coalition of a large number of monasteries in the fifth, sixth, and seventh centuries” (179). Moosa attacks this claim, commenting on how no other sources, besides the Letter of the Monks of Syria Secunda to Pope Hormisdas and other letters cited by the Maronites, discuss the Monastery of Maron as the head of a coalition of monasteries (78). Moosa also questions the claim that the 350 massacred monks were Maronites, commenting how “The letter ... indicates that the majority of the monks came from all over Syria Secunda and not from one monastery such as the Monastery of Marun” (83). It should also be noted that the excerpt quoted above, discussing the 350 massacred monks, does not claim that all the slain monks were Maronites.

Moosa attempts to demonstrate that the Maronites were originally anti-Chalcedonians, who were forced by Emperor Heraclius to accept Monothelitism, relying on the testimony of Patriarch Dionysus Tal Mahri of the Syriac Orthodox Church, who wrote in the early ninth century (95). During his reign, Emperor Heraclius formulated the doctrine of Monothelitism, the doctrine that the two natures of Jesus Christ were united in one will (96). In the aftermath of the Byzantine-Sassanid War of 602-628, believing that the empire’s integrity was at stake, Heraclius began to enforce Monothelitism, leading the monks of the Monastery of Maron and others to accept the Council of Chalcedon, which had articulated the two natures of Christ (99). Relying on the testimony of Tal Mahri, Moosa notes that if the monks of the Monastery of Maron were Chalecdonians then they would not have been forced to accept the Council of Chalcedon, and Tal Mahri would have made note of it (100).

In 680, the Sixth Council, convened by Emperor Constantine Pogonatus, condemned Monothelitism as a doctrine, and this change in doctrine was transmitted to the Levant through Byzantine captives of the Caliphate (Moosa 103-104). This reversion to the original formula of two wills and two natures was accepted in major cities such as Damascus and Aleppo. As a result, a conflict emerged between the Chalecdonian Malkites, who accepted the Sixth Council, and the Maronites, who retained their belief in Monothelitism, over whether or not the two natures of Christ were united in one will and whether Christ’s natures remained separated after the union (Moosa 104). This dispute eventually culminated into violence in 745 CE, when according to Patriarch Tal Mahri, the Malkites were able to elect Theophilact Ibn Qanbara as Patriarch under the Umayyad Caliph, who Moosa believes to be Marwan II. The Malkites were given permission to persecute the Maronites into accepting their doctrine of the two wills of Christ in the Trisagion, an ancient hymn, but failed, leading to the creation of separate churches for the Malkites and Maronites (114).

Moosa notes that, in Tal Mahri’s account, the Maronites lacked a Patriarch when the Malkites marched against them and that the Maronites, and only began electing a Patriarch in the mid-eighth century, following their clash with the Malkites (114-115). As a result, this calls into question the validity of the sainthood and story of John Maron. Moosa doubts the validity of the story of John Maron but argues that, from available sources such as Ibn Batria, there was an abbot named John Maron in Syria, but he was not a bishop or patriarch. This abbot was most certainly a Monothelite and not a Catholic (172). The sainthood is called into question when reading the letter written by Pope Benedict XIV, expressing his views on the dispute between the Malkites and Maronites of Aleppo over thevsainthood of John Maron in the mid-eighth century. Pope Benedict XIV holds that John Maron was a Monoethlite heretic, citing William of Tyre and Sa’id Batriq, but he holds that the Maron discussed by Theodoret of Cyrus is a saint (171).

“Moosa doubts the validity of

the story of John Maron but

argues that ... there was an

abbot named John Maron in

Syria, but he was not a bishop or

patriarch.”

Since there is significant reason to cast doubt on the sainthood and life of John Maron, it is necessary to examine the claim that the Mardiates were Maronites, as Dau has argued that John Maron organized the Mardaites into an effective military force. Hojairi attacks this claim by citing the work of the Lebanese historian ‘Adel Isma’il’s work al-Marada’iyyun, al-Marada: man hum? Min ayna ja’u? wa ma hiya ‘ilaqatuhum bi-l-jarajima wa-l-Mawarina? (56). According to Isma’il, the historical evidence demonstrates that the Mardaites were stationed in Mount Lebanon at the time of the Islamic conquests, contradicting the dates listed by Dau (57). Isma’il also demonstrates that the Maronites and Mardaites share no historical, ethnic, or religious similarities and that by the time the Maronites began immigrating to Lebanon, the Mardaites had withdrawn 70 years beforehand (57). Alongside these arguments, Ismai’l argues that the Mardaites and Jarjiamah were different groups, contradicting the association between the Mardaites and Jarjiamah given by Dau and Tayah (56-57).

It must be noted that the accusation of Monothelitism is not new, and Tayah addresses it. Tayah points out that the Sixth Council, which others may refer to as the Third Council, did not reference the Maronites in their condemnation of Monothelitism, which specified a multitude of heresies and errors. Tayah addresses the dispute discussed by Tel-Mahri, arguing that the dispute was not over Monothelitism but the inclusion of “Who was crucified for Us” in the Trisagion, an ancient hymn, which the Syrians but not the Greeks or Latins used (Tayah 34).

Since the main points of controversy in the debate over the historiography of the early Maronite Church are covered, historical evidence exists to give credence to either side of the debate, specifically the works of Thomas of Haran, Maronite bishop of Kfartb and the Maronite Chronicle.

Thomas of Haran, or Tuma, was a Maronite bishop of Kfartb near Aleppo and the author of the Ten Treatises, one of the few Maronite works to be written before the 17th century (Moosa 6, 110). In the Ten Treatises, addressed to the Melkite Patriarch John of Antioch in 1089 AD, Thomas defends Monothelitism (Dau 335). The patriarch burned Tuma’s work, but Tuma produced a new copy, and when he was preaching in Lebanon near the end of the 11th century, a village priest from Farsha requested a copy of the Ten Treatises (Moosa 110).

While Dau does not seem to deny that Thomas was a Maronite, other Maronite writers, such as Jibra’il Ibn al-Qila’i and al-Duwayhi, deny that Thomas of Haran was a Maronite (Salibi 139). Neither one provides evidence, with al-Qila’i claiming that Thomas of Haran was a Jacobite agent and al-Duwayhi arguing that Thomas of Haran may have been a misguided Maronite.(Salibi 46, 140). As a result, the Ten Treatises support the argument that the Maronites had not been in perpetual union with the Catholic Church and were, at one point, Monoethlites.

Another early Maronite work is the “Maronite Chronicle,” believed to be written in the mid to late 7th century by a Maronite writer (Penn 56). Though only fragments of the original text survive, the surviving pieces describe a debate between the Miaphysites and the Maronites (Penn 55). However, the text does not comment on the nature of the debate, only informing us that in June 970, “the Jacobite bishops Theodore and Sabul came to Damascus, and before Mu’awiya they debated the faith with those of Mar Maron [i.e., the Maronites]”(“Maronite Chronicle.” 323). Due to the lack of information regarding the theological difference, the “Maronite Chronicle” does not support either side of the debate regarding the early history of the Maronites.

The final early Maronite work that will be examined is Kitab al-Huda, containing the rules and canons of the Maronite Church (Moosa 196). While the original copy is lost, an Arabic translation from 1069 survives. As with the Ten Treatises, Kitab al-Huda professes the doctrine of Monothelitism. Like the Ten Treatises, Maronite writers, such al-Duwayhi, accuse Thomas of Haran of distorting the text to defend Monothelitism (Moosa 196-197). However, al-Duwayhi fails once again to produce any evidence that Kitab al-Huda was distorted in any manner by Thomas of Haran (Moosa 198). Like the Ten Treatises, Kitab al-Huda contradicts the Maronite narrative of perpetual union with the Catholic Church and supports the argument that the Maronites were once Monoethlites.

From the Ten Treatises and Kitab al-Huda, it is clear that the criticisms leveled against the narrative of the perpetual union between the Maronite Church and the Catholic Church are corroborated by historical evidence. As a result, it seems that William of Tyre was correct in asserting that the Maronites joined the Catholic Church in 1182.

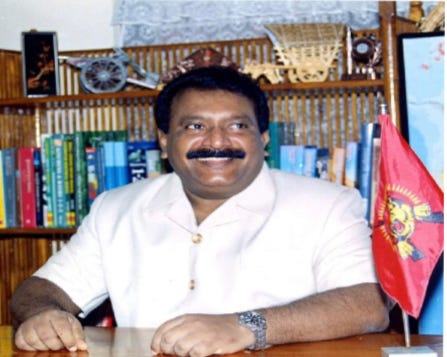

An Analysis of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam

Shruti Satish

The Tamil Tigers are a secular militant organization that sought to establish an independent Tamil state in the northeast region of Sri Lanka. This article will examine the functions of the Tamil Tigers, or LTTE, utilizing four explanations of their terror. These categories are as follows: organizational structure, individual and psychological explanations, strategies and tactics, and the role of media coverage on the Tamil Tigers.

The LTTE had a central governing committee headed by Velupillai Prabhakaran, who oversaw all missions conducted by the LTTE, including those of their military wing and political wing. The military wing was divided into four major sectors: the Sea Tigers, the Air Tigers, the Black Tigers, and the intelligence sector. The Sea Tigers were LTTE’s naval force led by Colonel Soosai, known for their several attacks on Sri Lankan ships. The Air Tigers were led by Colonel Shankar, who was given credit for the formation of this sector. The Black Tigers were the most infamous sector that carried out high-profile attacks, including the assassination of two heads of state. This sector was also responsible for the invention of the suicide belt, which is commonly used among terror organizations today. The intelligence unit was headed by Pottu Amman, who was second-in-command behind Prabhakaran. Notably, Pottu and Prabhakaran’s death by ambush is commonly accepted as the official end of this organization’s existence. As their political goal was to establish a Tamil state in the northeast region of Sri Lanka, “the LTTE had also set up a parallel civil administration within its territory by establishing structures such as a police force, law courts, postal services, banks, administrative offices, television, and radio broadcasting station, etc. The most prominent of the LTTE’s ‘state structure’ is the ‘Tamil Eelam Judiciary’ and the ‘Tamil Eelam Police’. The Tamil Eelam Police reportedly had several wings, including traffic, crime prevention, crime detection, information bureau, administration, and a special force.

LTTE cadres collected taxes, its courts administered their version of justice, and the entire law and order machinery was LTTE-controlled,” making this terrorist organization almost as complex as a government’s organizational structure1. What made the LTTE so successful in their attacks was their ability to combine two strong frameworks of structure into one. According to Martha Crenshaw2, there are two major frameworks: one that resembles a pyramid-like hierarchy and another that resembles a starfish or the spokes of a wheel. While the pyramid hierarchy is most common, using a central committee to handle different sectors of a group aids in the organization’s clandestinity. Crenshaw demonstrates the starfish model by using the metaphor that as one head gets cut off, another will grow in its place.

This type of replaceability is necessary for groups to survive covert government operations that may take the lives of heads of sectors. The LTTE, however, was not efficient at replaceability, thus the organization died along with Chief Prabhakaran and Pottu in 2009. Otherwise, this organization followed a hierarchy that resembled a preponderant order, mimicking a governmental structure, with different heads of sectors to not have one person communicating all attack criteria.

The LTTE’s cadres were internationally recognized for their discipline, dedication, determination, and motivation, and were considered one of the most sophisticated and dangerous terrorist groups by some counter- terrorism organizations, such as the FBI in 20084. These recruits underwent a rigorous four-month training program that included handling weapons, battle and fieldcraft, communications, explosives, and intelligence gathering, as well as a physically demanding regimen and rigorous indoctrination. However,this training was implemented brutally and collectively, with the intent of warning those who disobeyed. This brutal treatment had a long-lasting psychological impact on the individuals, making them more resilient and determined to carry out the LTTE’s objectives. The United States Army Special Operations Command identifies that “individual differences disappear in the face of powerful unifying forces,” and in this case that unifying force is fear and forced obedience,” and in this case that unifying force is fear and forced obedience.

Children were especially affected by these merciless methods, as most of them did not join voluntarily but were taken from their families at young ages, sometimes as young as ten. The Sri Lankan Directorate of Military Intelligence estimated that around sixty percent of LTTE cadres were under the age of 18, and the majority of the dead LTTE cadres were boys and girls between ages 10 and 16. The LTTE’s military wing aimed to breed fighters that were “even more daring than the adults” by intensifying the training program. The group sought to instill ruthless personality traits in young children, resulting in a direct pipeline to embitter them to a point of no return. The LTTE’s goal was to assure total commitment from its recruits and to instill the discipline and resolve needed to carry out their missions.

To discuss strategic explanations and tactics, we can refer to Andrew H. Kydd and Barbara F. Walter’s five principal strategies in terror groups to further this analysis: attrition, intimidation, provocation, spoiling, and outbidding. Attrition is the tactic used to demonstrate to the opposing party that the grouphas the capability to inflict severe damages if changes are not made to the status quo. According to Stanford’s Mapping Militant Organizations website, the LTTE’s victims were always those who opposed their goal of establishing an independent state for Tamilians. The Sri Lankan military, politicians that outwardly opposed them, police, and sporadic civilian targets seem to make up the majority of their selected attacks. Attrition is displayed in their high-profile attacks using the Black Tigers, demonstrating the extent of their capabilities. Proving that they can attack highly secured officials without any warning and at any time is evidence of their abilities as a terrorist organization.

Next, we have intimidation of civilians by inflicting brutal punishment for disobedience and opposition. The Human Rights Watch group states that forced recruitment was a substantial method utilized by the LTTE, with frequent targets being Tamil11. After the Indian Peace Keeping Force was established in 1987, the LTTE experienced a shortage of combatants due to the increase in casualties. This forced them to begin forcibly recruiting women and children from the areas under their control. The LTTE made sure to keep civilians in line and gather involuntary support through this method of intimidation.

The strategy of provocation was not as prevalent in this group as the others, yet there may still exist a slight correlation. Near the end of the group’s lifespan, Prabhakaran decided to flood the lands of Sinhala farmers by destroying dams in the region, galvanizing hatred from the Sinhalese majority government who in turn assassinated Prabhakaran along with others shortly after. This was an act of provocation because there had been a ceasefire since 2002, but Prabhakaran had initiated the war again resulting in his death, which sparked violent protests throughout the state of Tamil Nadu and gathered further support for the Tamilians of Sri Lanka.

The tactics of spoiling and outbidding are very similar, and both rely on the upsurge of other terrorist groups with the same motives and goals. However, these groups had far less discipline and resolve than the LTTE, and all of them were defeated by the LTTE by the end of the 1980s.

The media played a significant role in fundraising and garnering support amongst the Tamil Diaspora for the LTTE. The group was known to maintain connections with over 54 states, using publicity and propaganda to raise funds and transport armory. These networks spanned all over the world, with concentrations in five of the seven continents. What stood out most about LTTE’s media coverage was not the attacks or the fighting, but rather its criticism and acceptance of combative women. The LTTE’s acceptance of women as combative members was an unanticipated ideology at the foundation of the group, but cadres and leaders adopted a feminist ideology in 1983. The Women’s Front of the Liberation Tigers made its first appearance and evolved into what became known as the Birds of Freedom. Two women were the successors of the high-profile assassinations of heads of states, former Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and Sri Lankan president Ranasinghe Premadasa. The women of the LTTE were essential to the organization of the group, and this inclusion resulted in many favorable outcomes for the Tamil Tigers.

However, the public had many issues grappling with the stark contrast between the “traditional feminine woman and the new combative women.”16 Women were portrayed as unfeminine and androgynous; the LTTE had strict regulations about unattachment from love for both men and women. Articles represented women in uniform by describing them as masculine simply because they were in a combative uniform that held deep ties to masculinity. These implicit biases must be challenged on a large scale like media portrayal to see any desired changes to the status quo. Gonsalves argues that “the real battle for women who joined the fighting ranks of the LTTE may not have been the actual work as combatants but rather in dealing with their newly created image and the ensuing societal responses to this.”

The LTTE purportedly utilized these images to their advantage. They released statements about the confidence and strength of women and used them to increase sympathy amongst the Tamil population with accusations of the Sri Lankan Authority. Prabhakaran regularly made public speeches with ingrained feminist ideals to increase the willingness of women to join their liberation movement, and depending on the circumstances, women were utilized in media portrayals to bring attention to and amass aid in their Tamil crusades.

Although initially starting out as a guerrilla force, the LTTE increasingly came to resemble that of a conventional fighting force with a well-de-veloped military wing that included a navy, an airborne unit, an intelligence wing, and a specialized attack unit which exuded power and authority throughout their regions by means of kidnappings, ransoms, extortion, and bombings. The organizations’ abduction of children to work within their armies, and their obsessions with feminist and equal portrayals had largely caused their rise to fame in South Asia and furthered their presence in the media. Closely resembling a governmental organization, the LTTE has been an incredibly well planned organization, which had an untimely fall due to a leader’s death. This analysis of LTTE’s organization structure, individual and psychological effects, its strategic tactics, and portrayal in the media proved that this was no simple organization. The establishment and execution of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam was a conscientious and deliberate effort to establish a Tamil state of Eelam in Sri Lanka, which had succeeded in a myriad of attacks due to their due diligence and organizational strategies.

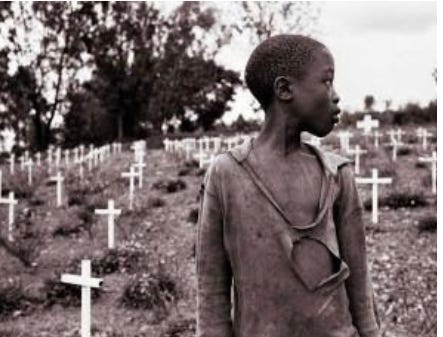

International Human Rights and the United Nations: A Case Study of the Rwandan Genocide

Abriana Malfatti

When the United Nations was created in 1945, an overarching duty for the nation-states signing into membership was also created the duty to promote human rights throughout the world. This duty has been reaffirmed by state laws and treaties over the years showing that states around the world still agree to help ensure the protection of international human rights laws abroad. When states sign these documents into law, they also agree that their utmost duty to the UN is to the protection of international rights above all else, even putting that duty over sovereignty in some cases.

The responsibility of states protecting human rights throughout the world can be seen in the preamble of the United Nations Charter. The preamble states the members of the United Nations have a responsibility,

“to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and nations large and small, and to establish conditions under which justice and respect for the obligations arising from treaties and other sources of international law can be maintained, and to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom”.

The important takeaway from this section is the use of the words “nations large and small” and the reference to “a larger freedom.” The reference to nations large and small creates an idea of equality throughout the world. The statute implies that if there is not to be a distinction between men and women then it is reasonable to interpret that there should not be any discrimination between nations either. It creates an understanding that all nations are of equal importance under the scope of international law.

The idea of “larger freedom” is also important to distinguish. Why did the drafters of the charter not stop at freedom? They could have said “regarding freedom” or “to protect freedom”, but the use of the word larger implies that there is a grander picture when discussing human rights on the world stage. Kofi Annan, Secretary General of the United Nations between 1997-2006 agrees with this idea of larger freedom going beyond the idea of basic human rights. Kofi writes that (larger freedom), “also goes beyond them, encompassing what President Franklin Roosevelt called ‘freedom from want’ and ‘freedom from fear’.” Both our security and our principles have long demanded that we push forward all these frontiers of freedom, conscious that progress on one depends on and reinforces progress on the others.” 2

Here Kofi refers to Roosevelt’s “four freedoms” speech in which Roosevelt advocates that the rights protected under democracy not only refer to those rights within one’s borders, but it also gives rise to the idea that the United States has a duty as an ally to ensure that the freedoms of democracy are made available to everyone in the world. The goal of the UN is to ensure a brighter and safer future for the world. Kofi reaffirms the idea that to secure this future we must secure the future of others as well. This brighter future will not be achieved if a state only focuses on the rights of its own nation, it needs to focus on the rights of other nations to move towards a more progressive world.

This idea of an obligation of the international community to the promotion of human rights has continued to be expanded upon throughout the years. The International Bill of Human Rights offers a new interpretation of what this duty entails while adding new ideas to what it entails at the same time. Adapted in December of 1948, the International Bill of Human Rights provides a foundation of what an international human right is and what it looks like to people around the world. It also reinforces the sense of universal responsibility in Article 1 by stating that “(all human beings) should act toward one another in a spirit of brotherhood.” The word brotherhood has strong connotations to its meaning. In a way, it implies that there is a sense of international friendship and family upon which the foundation of human rights relies upon. The word brotherhood has two important definitions in the Oxford Dictionary upon which this argument is based. One of the definitions is, “the feeling of kinship with and closeness to a group of people or all people.” This implies that the relationship that states have toward one another should be to act in a way of moral responsibility that one would act toward their sibling, rather than a way of malice and destruction, which is how the world largely operated before the creation of the UN.

The second definition of brotherhood demonstrates that a common interest shared by a group of people may also create a larger moral responsibility between them. The Oxford Dictionary also defines brotherhood as, “an association or community of people linked by a common interest, religion, or trade.” 5 In this case, the common interest would be the protection of human rights. All those who agree with the universal protection of human rights, which is every state that signed the bill, also agree to the bonds to one another that are also created. To deny a state aid in the protection of rights would be a denial of this idea of the universal brotherhood itself.

Article 2 of the International Human Rights Bill further supports the idea that the protection of human rights is not solely confined to a nation’s citizens. The bill demonstrates that one should not be discriminated against “based on the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs.” This clause further expands on the idea of universal brotherhood by explicitly stating one’s region is not a reason to deny them basic rights. It makes it even more clear. Discrimination means unequal treatment, and the law specifically states that treating people unequally based upon where they reside is a violation of the bill.

The international community has a duty to everyone living in the world, yet what duty does it impose for cases of the most outrageous of human rights violations? Does a state’s duty to protect international rights increase? According to the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, the answer is yes. Article 1 of the Genocide Convention states, “The Contracting Parties confirm that genocide, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law which they undertake to prevent and to punish.” The article goes beyond simply condemning genocide, rather it states a duty for the states to prevent the crime of genocide if possible. A state’s duty goes beyond ensuring that they do not commit genocide within the confines of their borders. The states’ universal obligation under the UN also means that a state is within the responsibility of a state to act if it is known that the crime of genocide is about to occur. This idea is expanded upon in Article 8 which calls the UN, “to take such action under the Charter of the United Nations as they consider appropriate for the prevention and suppression of acts of genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in Article 3”. This goes even further and creates an even larger obligation of the UN. It can even be argued that this clause implies that in times of crisis where lives are at risk, it is acting within the states’ right to violate sovereignty for the good of humanity.

International law proves a clear duty of the states belonging to the United Nations to the protection of human rights and the prevention of human rights violations from occurring. By signing these documents, states agreed to not only abide by international law but also have a duty to protect international human rights throughout the world. If all these statements are true, then what happened in Rwanda? What happened to allow the ethnic cleansing and killing of 800,000 Tutsi? More importantly, where was the duty and brotherly manner that the UN was abiding by when they motioned to pull out of Rwanda at its most vulnerable moment?

The Human Rights Council is effective at the bureaucratic level, but the UN still needs a way to have people on the ground to assist in protecting human rights in cases of political unrest and high violence. The solution they came up with was peacekeeping. Peacekeeping initially began in 1948 as a way for the UN to monitor the newly formed armistice agreement in the Middle East. The concept of peacekeeping entails sending troops into nations attempting to negotiate peace after a time of violence and helping them transition into a newly stabilized government. The troops are meant to prevent the already delicate peace from rupturing into destruction as well as protect unarmed civilians from the casualties of war. While peacekeeping can be effective such as in the case of Libera, it contains numerous problems and remains a highly criticized method by the UN. Some of the problems include a reliance on permanent members of the Security Council to endorse a mission for it to be successful, and not being able to have the resources to ensure that every nation will be able to have help. In 1993 permanent members of the Security Council demanded a stricter review of peacekeeping “to ensure that demands did not exceed capabilities.” (75) This meant that in most cases the UN must decide which lives are worth saving. All these issues are a part of why the peacekeeping mission in Rwanda led to a massive failure.

How did the UN make the decision not to put more effort into Rwanda? Many key factors went into this decision, but the biggest component was limited resources by the UN. The system of the UN relies entirely on the charitability and willingness of states to cooperate. Like any system of government, the UN only has so many resources at its disposal, which is whoever has the most money. One would believe that the UN has a mechanism in place to ensure that states are using their resources to help fulfill their duty to protect human rights under international law. This is not the case though, and often when a state does decide to intervene, that intervention has another political motive behind it.

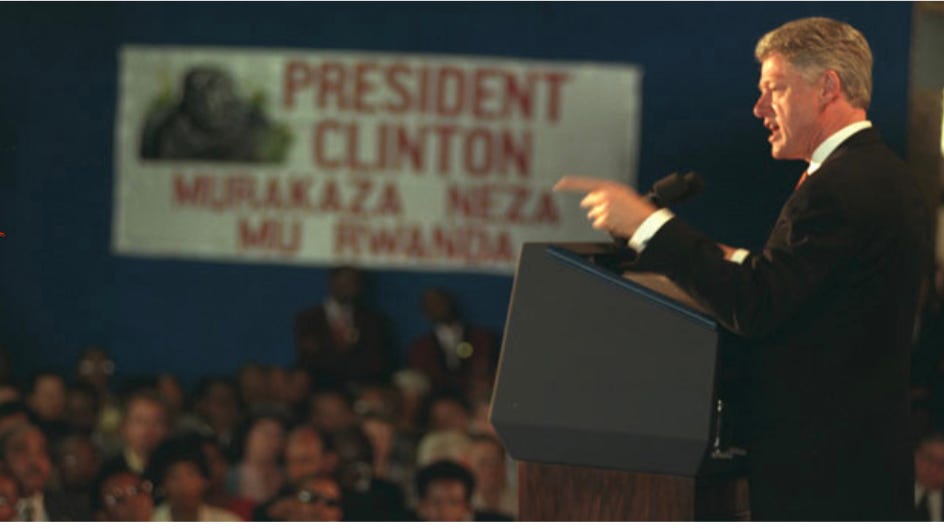

The political motive was an underlying issue with the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR). The United Nations required a win, especially after the failed cases of peacekeeping in both Somalia and Bosnia. Rwanda was meant to be that guaranteed win for them. To be able to put troops in Rwanda they needed a member of the permanent Security Council to put their backing behind UNAMIR. Ideally, this state would have been the United States, however, they refused to aid in another peacekeeping mission, especially after the American deaths that took place in Somalia. These American deaths were greatly broadcasted, and even overshadowed the ongoing conflict in Somalia itself. Due to this, support for the UN and the Clinton Administration at the time was way down. The Clinton administration wanted to avoid aiding another peacekeeping mission and send more troops in when they knew it would be met with wide opposition from their citizens.

UNAMIR did get a P-5-member state to back it, France. The problem was France supported the Hutus government despite the ethnic tensions and increasing violence towards the ethnic minority of Rwanda, the Tutsi. In Michael Barnett’s book Eyewitness to a Genocide, he notes, “Although the French might not have been able to foresee the genocide, they knew that Habyarimana’s regime and those close to the president were responsible for human rights violations. Not only did the French fail to use their leverage to demand that Habyarimana do what he could to stop these violations, but also, they continued to provide cover for the regime in various diplomatic for and to allow their military advisers to train and equip the Rwandan army and right-wing militias.”(135).” 9 Throughout the mission in Rwanda, France continued to offer support and aid to the Hutus, the group responsible for committing the genocide. To fuel the fire further, after the death toll of the genocide was realized by the rest of the world, France also volunteered to offer safety camps for the survivors. When France landed in Rwanda, they were met with cheers by the Habyarimana government thinking that they were here once again to aid them. While this was an embarrassment to the French government for the entire international stage to witness, they still abandoned their duty to protect the people of Rwanda who had had their human rights violated in one of the worst ways imaginable. At the safety camps for the victims of the genocide, France did not check who was taking refuge in the camps. This meant that there were Hutus hiding from prosecution. Even worse, Tutsi were forced to take sanctuary next to the same people who had just killed their families and communities’ months earlier. While France may have aided in a technical sense, in many ways it was worse, and they neglected their duty under international law. Here it can be argued that France put its political interests above those whose rights were at stake and who needed protection and safety the most.

Another major problem that went on with UNAMIR was the United Nations’ failure to inform the troops of all the information required for this mission to be successful. As mentioned above, this mission was meant to be an easy win that would allow the UN to redeem its hard power as an effective force on the international scale. At the time, the UN believed that both sides of Rwanda wanted peace. This issue of misinformation was not entirely the fault of the UN though, as mentioned all systems of government have limited resources. The UN had already stretched itself too thin in Somalia and Bosnia. The UN was also trying to tackle too many peacekeeping missions at once, overestimating its resources and capabilities. Policymakers assigned to this issue could only do so much with the limited resources they were given. This suggests overconfidence in the UN and its capabilities. One may argue that this was a fatal flaw within the UN that cost the lives of millions.

In addition, a lack of resources contributes to a lack of required information. The UN lost key documents dealing with the overall bureaucratic system of government. These documents were essential, and it can be argued that if these documents were not lost, the United Nations’ attitude, as well as the entire world, could have sung to a different tune. One of these key documents that got lost was Waly Bacre Ndiaye’s report on Rwanda before the deployment of UNAMIR. This report emphasized the possibility of a genocide occurring. Ndiaye stated, “The question of whether the massacres described above may be termed genocide has often been raised.” (100). 10 In addition, Ndiaye makes references to Article 2 of the Genocide Convention and makes it clear that what is happening in Rwanda is a violation of international law,

“The victims of the attacks, Tutsis in the overwhelming majority of cases, have been targeted solely because of their membership in a certain ethnic group, and for no other objective reason...Article II, paragraphs (a) and (b) might therefore be considered to apply to these cases. (100).”

Somehow this document did not reach the security council, the secretary general, or anyone who oversaw the overall operation of UNAMIR. This failure of the Bureaucratic system remains a precedent for many more documents, later this article will discuss how the UN should rectify this mistake and analyze what they should do to prevent this from happening in the future.

The document highlights two important points about what went wrong in Rwanda, the biggest one being that it used the term genocide. This was huge because at the time the entire world was afraid of referring to the situation as a genocide. Instead, they continued to call it a civil war gone wrong. By calling it a civil war rather than using terms like genocide or ethnic cleansing (which was taking place in Rwanda), the world was able to severely underplay the situation while keeping the citizens of the world in the dark about the atrocities occurring. This reduced the morale to come to Rwanda’s aid even though both sides were begging for help.

The failure of states refusing to call the genocide by its proper terms is an example of states neglecting their international duty outlined in international law. This can be seen from two perspectives: they were failing the people of Rwanda by not coming to their aid even though there was a violation of human rights occurring. As stated above, the states knew that what was going on in Rwanda was not a civil war that should be left up to state sovereignty, human rights violations on a massive scale were occurring. By calling it a civil war they kept the world in the dark, deceiving them about the situation. If the UN and key states such as the US used the word genocide, there is a strong argument that public opinions of aid in Rwanda would have changed. Everyone has a sense of inherent justice; this sense of inherent justice can be seen by just looking at the creation of the UN after World War II and the call to punish those who helped commit the genocide during the holocaust during the Nuremberg Trials.

Another way the UN drastically failed in Rwanda was that it did not hold member states accountable for neglecting their duty to protect human rights. Barnett notes,

“The public apologies rarely detailed their short comings, providing merely generic references to ignorance of the lack of political will and avoiding specifics about what they did during the war. The same individuals who were ready to establish a war crimes tribunal to prosecute those who carried out the killing were unwilling to come clean regarding why ignorance they tried to stop the killer.” (225).

The states continued ignoring and failing to live up to the duty upon which they had agreed. By letting the states not intervene and by letting them use ignorance to make up for their behavior, the UN is essential in saying that international law does not matter. After all, how effective can a law be if there is nothing to keep one from getting away with continually violating it?

Everyone has a sense of inherent justice…

It is safe to say that the UN failed to live up to this purpose during the Rwandan genocide. The UN failed to promote peace and security in Rwanda by turning a blind eye to the increasing death toll and cases of ethnic cleansing. It failed to promote security by attempting to pull troops out of Rwanda just when their government was killing them. France knew about the human rights violations and who was committing them, yet they did nothing to remove those threats of peace to the nation. Lastly, the UN failed to deliver justice under international law to the victims of the genocide.

It was already touched upon that the UN failed to keep states accountable for their actions in Rwanda, but it can also be argued that they failed to deliver proper justice for the victims of Rwanda during the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. While the people responsible for the genocide were ultimately tried and prosecuted, the process for such justice took 16 years to complete. The genocide was 100 days. The people of Rwanda had to watch their neighbors, friends, and family die for months and waited over a decade for justice.

What happened in Rwanda was a failure to humanity. It was a devastation that should not have happened. While it is hard to say for sure what could have happened if one thing went differently within the UN, one thing that scholars can agree on is that the UN failed the people of Rwanda. In Bill Clinton’s speech to the people of Rwanda, he says that,

“The international community, together with nations in Africa, must bear its share of responsibility for this tragedy, as well. We did not act quickly enough after the killing began. We should not have allowed the refugee camps to become a haven for the killers. We did not immediately call these crimes by their rightful name: genocide. We cannot change the past. But we can and must do everything in our power to help you build a future without fear, and full of hope.”

However, Bill Clinton’s words remain empty promises. The international community does have a responsibility to bear. They were obligated under international law to protect the people of Rwanda who had their basic human rights violated. While the people of Rwanda were being murdered daily, the United States was the nation that took the lead in failing to call the genocide what it was. There is a simple answer for why the United States referred to the events in Rwanda as a civil war rather than a genocide. If it was a genocide, it would be harder for them to avoid acting. By calling it a civil war, the United States was able to hide behind the blanket of sovereignty saying that it was not an issue under international law.

It was laid out in international law that the purpose of the United Nations was to create a more peaceful future after realizing the devastations of war. The very first line of the preamble for the UN charter states, “We the Peoples of the United Nations Determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind.”

Members of the United Nations, especially the permanent members of the Security Council (P-5), knew what was at stake. They also knew what was required of them, yet they continued to hide under the excuse of maintaining sovereignty and being ignorant about the ongoing violence. Barnett, who worked at the UN in New York during the time of Rwanda, responds to the United States’ claim of ignorance, “the United States was going to respond the same anemic way -- a point callously underlined in May when the genocide was well known but the United States refused to acknowledge its existence and opposed the plane to intervene. The United States cannot use ignorance as an excuse.”(236) This demonstrates that the P-5 members of the United States hold too much power. They can play politics with lives at risk and not be held accountable when they are in the wrong.

For the UN to move forward, there needs to be a check on the power of the Permanent Five. If these nations bring up the idea of sovereignty, the idea that they do not have to take orders from the international community, one should respond by showing them the language of the charter that addresses sovereignty. The charter reads, “The Organization is based on the principle of the sovereign equality of all its members”. 17 This clause does not simply dictate sovereignty, it adds that it is founded on the “sovereign equality of all its members”. States cannot simply pick and choose when they will abide by sovereignty, especially when the first duty established in the charter is the protection of peace and international rights.

For the international community to move forward, to live in the world that it originally envisioned back in 1945, there needs to be a new power structure created. There needs to be equality among members. The P-5 nations should not have any special powers. By giving them special powers, the UN is undermining the idea of equality amongst all states. The hands of the many should not be left within the hands of the few. As demonstrated in the case of Rwanda, the few abuse their power and do not always act under international law.

“While the people

responsible for the

genocide were

ultimately tried

and prosecuted, the

process for such

justice took 16

years to complete.

The genocide was

100 days.”

In addition, there needs to be a system in place that can hold members accountable for failing to live up to the overarching duties upon which they had agreed. In many ways, international law is analogous to a contract and should be thought of as such. If one violates a contract under common law, it is reasonable to believe that they will be held accountable for their actions for violating the contract. Both contracts and international treaties are agreed-upon documents in which rules and responsibilities are laid out by and for all parties involved. When states sign treaties, they knowingly do so. They are not coerced, and they have time to review the documents and amend them as they see fit. The clauses in question have not been amended though, they have stood the test of time, lasting decades. Meaning that for decades no state has challenged the duty laid out for them in international law.

If all of the above is to be held, it should also be in the realm of possibility that the P-5 member states would agree to have their powers checked. This will be met with opposition, of course. When one has power, they will now easily give it up. If one is to look at the overarching picture, one would see that there is much more at hand than a simple power game of politics. Over 1 million people died in Rwanda in 100 days. The United Nations was created to prevent an event like Rwanda from happening. If the United Nations is serious about ensuring these events do not happen to again, they need to check the powers of the Permanent Five nations.

The United Nations has a responsibility to all the citizens of the world. By failing to address these issues, they fail to do their job. Each day they fail to take inventory of their systemic issues is another day that people’s rights are at risk.

The Terrorist Identity and How it Develops

Isabelle Warren

There is an abundance of scholarly debate processes in which a person can develop a terrorist identity, including psychological and sociological causes. One basic understanding of terrorism begins with the perception of injustice or lack of identity, which causes an individual to join a terrorist organization.

Psychological and sociological causes can be explained in psychological terms through identity theory and narcissism theory. Jeff Victoroff, M.D., an Associate Professor of Neurology at the University of Southern California, has published many psychology and neurology-based articles about terrorism. He describes identity theory as he idea that, “candidates for terrorism are young people lacking self-esteem who have strong or even desperate needs to consolidate their identities” (Victoroff 22). There is a lack of personal understanding or independence that can increase a person’s need for purpose, which then manifests in violent action. This overlaps with narcissism theory, which, “prevents the development of adult identity and morality”, so when humiliated, “might reawaken the psychological trait of infantile narcissism...hypothesized to mobilize the expression of the desire to destroy the source of the injury” (Victoroff 23). The individual is experiencing anger toward themselves but exacting that anger on their political target. The development of infantile narcissism is a psychological process that would cause an individual to turn to terrorist violence.

In the article “Social Psychology, Terrorism, and Identity: A Preliminary Re-examination of Theory, Culture, Self, and Society” Michael Arena and Bruce Arrigo argue that “five organizing concepts from Structural Symbolic Interactionism (SSI) are employed. These include symbols, the definition of the situation, roles, socialization and role-taking, and the emergence of the self ” (488). This exploration of terrorist organizations explains that the first principle, symbols, can be understood as concrete objects like banks or embassies, targeted because they are, “emblematic of capitalism or Western influence” (Arena and Arrigo 488). In the framework of terrorism, there is a physical thing that symbolizes a nation or concept that the organization is against, and it, therefore, becomes the target of violence. Furthermore, the definition of the situation is “a process through which people assign meanings to and exchange meanings for the symbols in their environment” (Arena and Arrigo 491). When terrorist organizations develop their perspective of a situation, like an imbalance of power, the group can decide whether violent actions are necessary and warranted.

The next component, roles, is explanatory of how individuals fit into the terrorist organization as a whole. Adopting a specific role comes with “an adherence to specific values, norms, attitudes, codes of conduct, and obligations...infused with the interpretation of concrete and abstract symbols, as well as specific definitions of a given situation” (Arena and Arrigo 493). The predetermined roles for individuals create an easier transition into the beliefs and actions of the organization and can influence the way that individuals perceive injustices.

“...the individual seeks

to validate the salient

aspects of themselves

within the

organization and

create a stronger bond

to that specific

identity.”

The component of socialization and role-taking “emphasizes how individuals come to embrace the appropriate interpretation of symbols, definition of situations, and the components of the roles they experience or undertake” (Arena and Arrigo 495). This is where the individual comes into contact with someone who shares the terrorist beliefs with them and allows them to understand the shared definition of the situation. An individual understands the identity and the violent actions that will be done as part of the organization. Additionally, the social learning theory of aggression supposes that, “violence follows observation and imitation of an aggressive model” (Victoroff 18). When young people see active terrorist groups in their area, they can see therole they could play in that organization and could develop their own understanding of necessary violence. Finally, the component of the self, where “individuals have numerous identities comprising their self; however, these identities... are hierarchically ordered into a structured system that engenders aspects of salience and priority” (Arena and Arrigo 498). In this stage, the individual seeks to validate the salient aspects of themselves within the organization and create a stronger bond to that specific identity. All of these components create a sociological system in which an individual can become accustomed to a terrorist organization in their society and begin to share their views.

Left-wing and right-wing extremists experience a different understanding of the world and, according to some studies, even come from different demographics of American society. Jeff Victoroff, in “The Mind of the Terrorist”, discusses a study from 1990 that analyzed the socioeconomic backgrounds of left- and right-wing terrorists active during the 1960s-1970s from FBI interviews. Handler found that, “women represented a much larger proportion of left- than right-wing terrorists (46.2 vs 11.2 percent), college completion was much more common among left- than right-wing terrorists (67.6 vs 19.0 percent), blue-collar occupation was more frequent among right- than left-wing terrorists (74.8 vs 24.3 percent), and there was a trend for both left- and right-wing terrorists to achieve low-to-medium income levels even if they had college education” (Victoroff 7). This study provides an understanding of how specific identities and backgrounds can sympathize with individuals with different social issues.

An individual transitions from holding a belief to becoming an actual terrorist through radicalization and alienation, in addition to the psychological and sociological processes previously described. White explains, “radicalization is believed to cause terrorism when the motivation for political change combines with the process of developing deep-seated doctrines that lead toward violent action” (30).