In 2023, Azerbaijan launched a successful offensive that led to the dissolution of the Republic of Artsakh and cemented the country’s control over the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh.1 Following Azerbaijan’s victory, officials tore down a statue in Martuni, known in Azerbaijani as Khojavend dedicated to Monte Melkonian.2 Melkonian is remembered for his service as a commander in the First Nagorno-Karabakh War. However, upon closer inspection, Monte Melkonian’s story is an unusual one. Upon his appointment as commander, he had spent two years in the country.3 Melkonian was a California native who initially had little familiarity with the Armenian language or culture.4

The question is how did a third-generation Armenian from California become so committed to Armenia? What drove Monte Melkonian to view Nagorno-Karabakh as a sacred cause, remarking that “If we lose Karabakh, we turn the final page of the Armenian history.”5 To understand Monte Melkonian’s story requires understanding the modern history of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Figure 1. Political Map of Armenia. Accessed on December 6, 2024, Map, Nation Online Project, https://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/map/armenia_map.htm.6

From Independent Republics to Soviet Socialist Republics

In 1917, the end of the First World War left a devastating impact on Armenians. Two years prior, the Ottoman Empire initiated the Armenian Genocide by arresting 250 Armenian intellectuals on charges of collaboration with Russia and previous Armenian resistance.7 Following the arrests, the Empire began deporting Armenians from Eastern Anatolia to concentration camps located on modern Turkey’s southern border and the Syrian desert of Deir ez-Zor.8 On these routes, irregular Turkish forces—occasionally assisted by local Kurds and Circassians—carried out massacres against Armenian deportees.9 The Armenian Genocide lasted from Spring 1915 to Autumn 1916, resulting in 664,000 to 1.2 million deaths.10

Amid the First World War and the Armenian Genocide, Russia conquered Armenian regions of the Ottoman Empire. However, following the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Russia withdrew from the war and returned all conquered territory to the Ottoman Empire.11 Russia’s withdrawal from the war saw the emergence of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic or TDFR, comprising much of modern-day Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia. However, the TDFR dissolved just a month later due to inner turmoil.12

As the TDFR dissolved, the Republic of Armenia declared independence on May 28, 1918, becoming the first independent Armenian state since the Middle Ages.13 However, the fledgling Armenian state found itself waging three consecutive wars. First, Armenia and Georgia went to war over the territories of Lori and Akhalkalaki—home to substantial Armenian populations—in October 1918.14 By January 1919, a British imposed ceasefire and preliminary peace ended the war.

In November 1918, war broke out between Azerbaijan and Armenia over Zangezur and Nagorno-Karabakh. Following the end of World War 1, Karabakh Armenians asked Armenian general Andranik Ozanian to bring Nagorno-Karabakh within Armenia’s orbit.15 However, British Major General William M. Thomson rebuked Ozanian’s attempt, ordering him to return to his base in Zangezur.16 Ozanian obeyed, believing Thomson’s promise that all border disputes would be resolved at the Paris Peace Conference.17 However, Major General Thomson reneged his promise and recognized Azerbaijan’s claim to Zangezur and Nagorno-Karabakh. Furthermore, he placed 400 British soldiers in Shushi to secure Azerbaijani claims, leading General Ozanian to demobilize his troops and go into exile.18

In 1919, the Armenian National Council of Karabakh refused to recognize the authority of the Azerbaijani government. In response, the Azerbaijani governor placed the region under a tight economic blockade. Additionally, he attacked the city of Shushi to subjugate the Armenian population.19 Due to this immense pressure, the National Council recognized Azerbaijani rule in exchange for cultural autonomy.20 However, Karabakh Armenians became emboldened to resist Azerbaijani rule following Azerbaijan’s failure to capture Zangezur. They continued to confront Azerbaijani forces until 1920.21 On April 28, 1920, the Soviet Red Army marched into Baku, Azerbaijan, ushering in the Azerbaijani Socialist Soviet Republic.22 Armenia met a similar fate when Soviet soldiers invaded on November 29, 1920.23 However, Armenia did not become a Soviet republic until December 2, 1920.24

As the Soviet Union invaded the Caucasus, Turkish forces led by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk attacked the Armenian-held territories of Kars and Ardahan in September 1920. By December 4, 1920, Armenia concluded the Treaty of Alexandropol, forfeiting claims to pre-1914 Turkish territory. Additionally, the treaty stipulated Armenian recognition that no Armenian minorities existed in Türkiye.25 However, the treaty became invalid, because it was signed as the First Armenian Republic dissolved. Due to the Soviet Union’s desire to maintain warm ties with Mustafa Kemal, they signed the Treaty of Moscow, affirming the borders agreed upon in the Treaty of Alexandropol.26

Despite Armenia and Azerbaijan’s Sovietization, the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh remained unresolved. Initially, the consensus among Soviet officials supported Armenian claims to Nagorno-Karabakh. In fact, following the Soviet invasion of Armenia, Soviet Azerbaijani officials maintained that the regions of Karabakh, Nakhichevan, and Zangezur belonged to Armenia.27 Furthermore, a plenum of the Communist Party’s Caucasian Bureau ruled that Karabakh should be given to Armenia.28 However, on July 5th, 1921, the Bureau reversed its decision, making Karabakh an autonomous oblast under Azerbaijani control.29

The Bureau’s reversal resulted from the Soviet Union’s desire to maintain good ties with Mustafa Kemal. The Soviets believed that Kemal could be an asset in exporting their ideology. Thus, while negotiating the Treaty of Moscow, Turkish negotiators asked that Karabakh and Nakhichevan be placed under Azerbaijani control.30 The Caucasian Bureau acquiesced to the former demand, and Nakhichevan became an autonomous republic under Azerbaijani authority.31 Thus, by the time Stalin rose to power, the groundwork of the future Nagorno-Karabakh wars was laid.

A Boy from California Joins the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia

In Visalia, California, Zabelle and Charlie Melkonian welcomed their third child—Monte Melkonian—on November 25, 1957.32 Melkonian’s upbringing was not steeped in Armenian cultural or political history. Speaking with The Los Angeles Times, his father commented, “We didn’t talk up the Armenian cause at home. We didn’t drum the Turkish genocide into their heads.”33 Markar Melkonian–Monte’s older brother– corroborates his father’s claim. In My Brother’s Road, Markar notes that the Melkonian children possessed a sense that they were ethnically Armenian. However, their awareness did not amount to anything more than that. Their parents were not well-read on Armenia, and they did not have any grandparents to learn from.34

Markar traces his brother’s commitment to Armenia to two moments during a fifteen-month family trip to Europe in 1969.35 First, when the family settled in Spain for a couple of months, Charles Melkonian signed his boys up for Spanish lessons at the Academia Almi in Castellon.36 One day, their teacher—a college student named Senorita Blanca—asked twelve-year-old Monte where he was from. He answered that he was from California. His answer did not satisfy Blanca who asked in clearer terms, “where did your ancestors come from?”37 At this point in his life, Monte viewed himself as an American, but Senorita Blanca’s question left Monte pondering his identity.

In the following spring, the Melkonian family continued their journey across Europe. Along the way, Zabella Melkonian decided to visit her ancestral town of Marsovan—now Merzifon—in Eastern Türkiye.38 The Melkonians dined with the family of Vahram Karabents–one of the city's three remaining Armenian families. During their stay, Karabents showed the family their maternal grandfather’s house.39 Speaking on this event, Seta Melkonian–Monte Melkonian’s wife–commented that Melkonian’s trip to Türkiye left a lasting impact on him, because he saw “the place that had been lost.”40

Monte’s return from Europe in 1970 marked the beginning of his commitment to Armenia. As a student at UC Berkeley, he became involved in the Armenian Student Association.41 By 1978, Melkonian graduated from UC Berkeley after only two and a half years.42 While offered the opportunity to pursue graduate studies in archaeology at the University of Oxford, Monte opted to pursue a life of militancy in service of Armenia. His decision led him to join the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia, or ASALA, in 1980.43

In 1975, Hagop Hagopian–an Iraqi-Armenian who fought with Palestinian militant groups–founded the ASALA in Beirut, Lebanon.44 With a Marxist orientation, ASALA committed itself to the liberation of the Armenian ancestral homeland—comprising parts of the then-Soviet Union, Türkiye, and Iran.45 Monte would rise from an ASALA recruit to second-in-command, helping to plan and carry out various operations.46

Melkonian’s most infamous operation as an ASALA commando involved the assassination of a Turkish official in Greece. In mid-July of 1980. Monte was tasked with finding and striking a Turkish target in Greece. However, he failed to find a suitable target after stalking the Turkish embassy in Athens for a few days. He returned to Lebanon to seek Hagopian’s advice on what to do and soon returned to Athens.47 On July 31, 1980, he shot at four passengers in a car with diplomatic license plates and tinted windows in front of the Turkish embassy.48 Monte later learned that he had killed an administrative attaché to the Turkish embassy–Galip Osman. However, there was another victim: Osman’s daughter. Osman’s wife and son survived Monte’s attack. According to Markar, Monte regretted killing Osman’s daughter, deeming it an indefensible crime to kill innocents. To compensate for his crimes, Melkonian committed himself to preventing others from repeating his mistakes.49

Monte’s commitment to reducing civilian casualties contributed to growing tensions between him and Hagop Hagopian over ASALA’s trajectory. Overtime, Monte became increasingly discontented with ASALA. He began advocating for a more political approach and limiting attacks to Turkish officials.50 In contrast, Hagopian lacked Monte’s concern for civilians, believing suicide bombings generated more publicity.51

Two events exacerbated the tensions between Melkonian and Hagopian. The first flashpoint involved ASALA’s flight from Beirut in the wake of the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in June 1982.52 The next breaking point came with ASALA’s orchestrated attack on the Orly Airport Attack in 1983–leaving 55 wounded and 8 dead.53 However, the final break between the pair came when one of Melkonian’s partisans killed two of Hagopian’s supporters. In retaliation, Hagopian tortured and killed two of Melkonian’s closest associates while recording everything.54

Following the murder of his closest associates, Monte went underground.55 While underground, he founded the ASALA Revolutionary Movement.56 However, in 1985, French authorities discovered “two explosive devices and a map showing the travel route of a Turkish diplomat” in Melkonian’s room.57 He was subsequently sentenced to six years in French prison.

On January 16, 1989, Melkonian was released from prison but faced potential extradition to the US. To avoid repatriation, he boarded a flight to South Yemen on February 5, 1989.58 On February 18, 1989, in Aden he reunited with his partner—Seta. However, the couple stayed in Yemen for about a month. They moved from Yemen to Czechoslovakia then travelled between Yugoslavia, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria until 1990.59 A few weeks into February in 1990, Seta took a train to Moscow and then a plane to Yerevan with the goal of getting her fiancée to Armenia. In the meantime, Monte had returned to Yugoslavia by March 15 and kept a low profile.60 In early June, Seta managed to convince the leaders of the Armenian National Movement to formally invite her fiancée under an alias to Armenia. He arrived in Yerevan from Varna, Bulgaria on October 5th, 1990.61

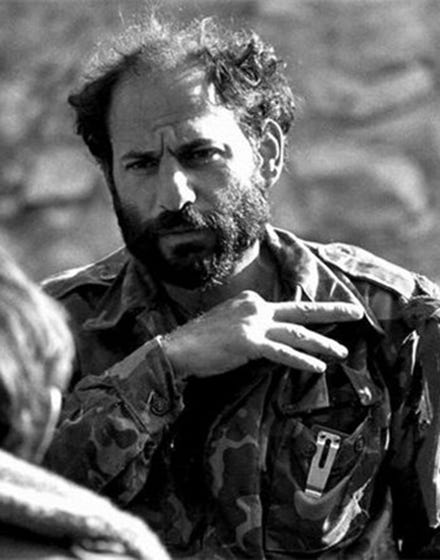

Figure 2. [Monte Melkonian]. Accessed on December 6, 2024, Photograph, 100 Lives, https://legacy.auroraprize.com/en/armenia/detail/10162/monte- %25E2%2580%259Cavo%25E2%2580%259D-melkonian%252C- commander-of-artsakh-war-for-independence-.62

Melkonian in Armenia: The First Nagorno-Karabakh War

During Monte’s imprisonment, Nagorno-Karabakh experienced significant political upheaval. Since the introduction of glasnost in 1986, thousands of Armenians from across the Soviet Union sent petitions to Moscow asking for unification between Nagorno-Karabakh and the Armenian SSR.63 As the calls for unification grew, the Soviet of Karabagh adopted a resolution on February 20, 1988 calling on Azerbaijan and Armenia to facilitate the unification of Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia.64 Despite the Regional Committee of Karabakh’s decision to affirm the Soviet’s resolution, Moscow refused to accept Armenian demands.65 No border modifications or status changes were made until January 1989 when the Supreme Soviet of the USSR decreed that Karabakh would remain part of Azerbaijan. However, the region was placed under special administration with Moscow appointing a viceroy to govern the region.66 In November 1989, a military regime under General Safonov—who wanted to reunite Karabakh with Azerbaijan—replaced the administration.67 However, following the failed coup against Gorbachev and Yeltsin’s victorious outcome, Russian and MVD forces withdrew from the region.68 An all-out conflict between Azeris and Armenians became inevitable with the proclamation of the Mountainous Karabakh Republic–a state independent of Armenia–on September 2, 1991.69

Within a year of his arrival in Armenia, Melkonian became involved in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. In 1991, he gained permission from the Defense Committee in Yerevan to form a detachment. He named it the “Patriotic Detachment” and led it under the alias “Avo.”70 Initially, the Defense Committee did not deploy Melkonian to Nagorno-Karabakh, fearing his potential apprehension by the Soviets due to his status as a convicted international terrorist.71 Instead, the Defense Committee requested that Avo’s detachment and the Special Designated Group–another detachment–inspect Armenia’s northeastern border with Azerbaijan.72 Monte’s first deployment to Artsakh would be on September 12, 1991.

However, Monte became legendary during his tenure as the Commander of the Martuni district.73 Initially, Avo struggled to assert his authority due to the disobedience of the Aramo and Arabo detachments. These Armenian detachments disobeyed Melkonian’s orders on two egregious occasions. On February 16, 1992, the Arabo and Aramo detachments attacked the village of Karadaghlu without prior authorization, failing to capture it.74 When the village was captured the next day under Monte’s command, the Aramo and Arabo fighters butchered over 53 Azeris, including several noncombatants.75 Shortly afterward, on February 26, some 2,000 Armenian soldiers–with Arabo fighters participating–successfully captured the Azerbaijani village of Khojalaju.76 However, in the aftermath of their victory, they killed 613 Azerbaijani civilians according to estimates by the Azerbaijani government.77 Monte was furious. During the battle of Karadaghulu, he gave strict orders not to harm captives, but the Arabo and Aramo detachments disobeyed his orders.78 Now, they had done the same in Khojalaju. While Monte managed to convince his military superiors to expel the Arabo and Aramo detachments from Martuni, he failed to persuade his superiors to disband or expel them from Karabakh completely.79

As time progressed, Monte made great strides in defending Martuni and helping Nagorno-Karabakh maintain its new-found independence. First, Monte and Colonel Haroyan–one of four officers tasked by Yerevan to create an officer corps in Karabakh–created a centralized military command for the Martuni district.80 Through summer and early fall 1992, the pair created nine municipal and sub-district headquarters for the Martuni district that were accountable to Monte’s office.81 Furthermore, Melkonian and Haroyan created a new ground-force structure and redistributed their military forces.

Second, Monte Melkonian successfully led the Kelbajar offensive. In early 1993, Monte expressed the need to control the area between the borders of Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia proper.82 By April 3, 1993, Melkonian had captured everything from the Mrav Mountains in the north to the Lachin Corridor in the south. The offensive allowed the Republic of Armenia to be connected via-land with Nagorno-Karabakh.83

However, Melkonian did not live to see the end of the war. On June 12, 1993, Monte and his companions passed through the village of Marzili after having completed a military operation in the Aghdam region of Azerbaijan.84 Arriving at a crossroads, the entourage noticed an armored vehicle with a group of soldiers huddled around it. One of Monte’s companions– who was wearing an Azerbaijani military uniform—approached the soldiers to ask if they were Armenians. When they replied in Azerbaijani, Komitas opened fire and quickly retreated. In the ensuing firefight, Monte’s died from a piercing caused by a large shell fragment. The small entourage managed to fend off the Azerbaijani soldiers until Armenian relief forces arrived, capturing one of the Azerbaijani soldiers. Posthumously, Melkonian received the highest honors of the Republic of Armenia and the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh: National Hero of the Republic of Armenia and Hero of Artsakh.85

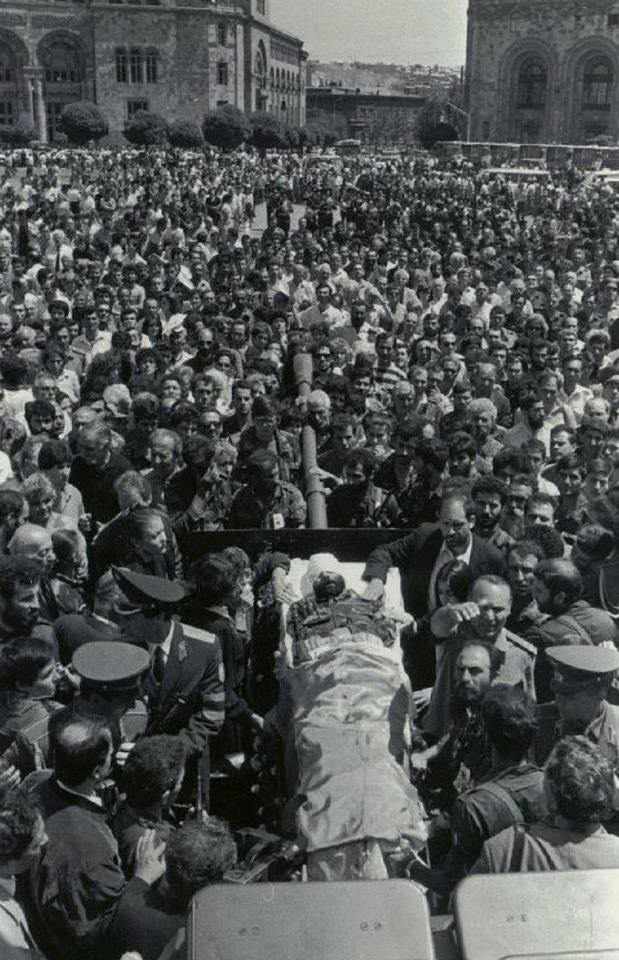

Figure 3. HovoYerevan, Monte Melkonian’s Funeral, 1993, Photograph, Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/65903724@N04/8666330421/.86

Present Day: Artsakh is Lost

By the end of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War in 1994, Armenia controlled the entirety of Nagorno-Karabakh and partially or wholly controlled seven adjacent districts.87 The Bishkek Protocol—brokered by Russia—left Nagorno-Karabakh de-facto independent but reliant on Armenia.88 Between 1994 and 2020, there have been intermittent clashes between Armenian and Azerbaijani forces, with 2016 seeing the most intense clashes before the Second Nagorno-Karabakh war in September 2020.89 The war ended after 44 days with a Russian-brokered ceasefire that left Azerbaijan with firm control over most of Nagorno-Karabakh. The protocol established the Lachin Corridor to connect Armenia with the remaining territory of Artsakh.90

However, in December 2022, Azerbaijan blockaded the Lachin Corridor. The blockade lasted until September 2023, causing acute shortages in Nagorno-Karabakh.91 By August 2023, there was a lack of essential medical supplies, food, fuel, and hygiene products.92 While a compromise to lessen the blockade was reached on September 3, 2023, Azerbaijan launched an offensive against the enclave on September 19.93 After one day, the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh capitulated and agreed to be dissolved on January 1st 2024.94 By September 30, 2024, 100,417 of Nagorno-Karabakh’s almost 120,0000 population fled to Armenia, leading to accusations of ethnic cleansing against Azerbaijan.95

In the wake of the mass exodus of Armenians from Artsakh, there is a growing concern about preserving the Armenian heritage of the area. This article is an attempt to contribute to the preservation of Nagorno-Karabakh’s Armenian history by bringing awareness to the life of one of its most important figures. By tracing the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh, “An American in Armenia” brings awareness to how current day events unfolded. In turn, understanding the origins of the conflict allows the reader to understand how Melkonian’s life became intertwined in the destiny of Artsakh.

Bibliography

100 Lives. [Monte Melkonian]. Accessed on December 6, 2024. Photograph. 100 Lives. https://legacy.auroraprize.com/en/armenia/detail/10162/monte-%25E2%2580%259Cavo%25E2%2580%259D-melkonian%252C-commander-of-artsakh-war-for-independence-.

Aleksandrovich Mints, Aleksey, and Ronald Grigor Suny. “Modern Armenia.” Encyclopedia Britannica, Nov. 27, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/place/Armenia/Modern-Armenia.

Arax, Mark. “COLUMN ONE: The Riddle of Monte Melkonian: Family and Friends Wonder How a Visalia Cub Scout with No Interest in His Roots Ended up as a Terrorist and Armenian War Martyr.” Los Angeles Times, Oct. 9, 1993. www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-10-09-mn-43923-story.html.

Associated Press. “Almost all ethnic Armenians have left Nagorno-Karabakh.” The Guardian, Sept. 30, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/sep/30/almost-all-ethnic-armenians-have-left-nagorno-karabakh-azerbaijan

Baghdasaryan, Edik. “June 12, 1993 – Monte Melkonian Met Death On the Battlefield.” Hetq, Jun. 12, 2012. https://hetq.am/en/article/2045.

Baumer, Christoph. History of the Caucasus: Volume 2: in the Shadow of Great Powers. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2023. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ohiostate-ebooks/detail.action?docID=30747349.

Directorate of Intelligence. The Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia: A Continuing International Threat. CIA-RDP85T00283R000400030009-2. CIA, Jan. 1, 1984. https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP85T00283R000400030009-2.pdf.

Droin, Mathieu, Tina Dolbaia, and Abigail Edwards. “A Renewed Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Reading Between the Front Lines.” CSIS, Sept. 22, 2023. https://www.csis.org/analysis/renewed-nagorno-karabakh-conflict-reading-between-front-lines.

Edwards, Christian. “Nagorno-Karabakh will cease to exist from next year. How did this happen?” CNN, Sept. 28, 2023. https://www.cnn.com/2023/09/28/europe/nagorno-karabakh-officially-dissolve-intl/index.html.

Harding, Luke. “‘They want us to die in the streets’: inside the Nagorno-Karabakh blockade.” The Guardian, 22 Aug. 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/aug/22/inside-nagorno-karabakh-blockade-armenia-azerbaijan.

Hovhannisyan, Nikolay. “Monte Melkonian: A talented scholar and defender of Karabakh's self-determination.” ARMENPRESS, May 21, 2014. https://armenpress.am/en/article/762659.

HovoYerevan. Monte Melkonian’s Funeral. 1993. Photograph. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/65903724@N04/8666330421/.

Institute for Armenian Studies of Yerevan State University: History of Armenia. “Melkonian Monte.” Accessed on November 30, 2024. http://www.historyofarmenia-am.armin.am/en/Encyclopedia_of_armenian_history_Monte_Melqonyan.

International Crisis Group. “The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: A Visual Explainer.” Sept. 16, 2023. https://www.crisisgroup.org/content/nagorno-karabakh-conflict-visual-explainer.

Malkasian, Mark. Gha-ra-bagh! The Emergence of the National Democratic Movement in Armenia. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1996.

McGown, Abigail. “Azerbaijan’s Pressure on Nagorno-Karabakh: What to Know,” Council on Foreign Relations, Sept. 14, 2023. https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/azerbaijans-pressure-nagorno-karabakh-what-know.

McGuinness, Damien. “Nagorno-Karabakh: Remembering the victims of Khojaly.” BBC News, Feb. 27, 2012. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-17179904.

Melkonian, Markar and Seta Melkonian. My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia. London: I.B. Tauris, 2005.

Ministry of Defence of The Republic of Armenia. “Monte Melkonyan.” Accessed on November 30, 2024, https://www.mil.am/en/persons/64.

Mutafian, Claude. “Karabagh In the Twentieth Century,” in The Caucasian Knot: The History And Geopolitics of Nagorno-Karabagh, by Levon Chorbajian, Patrick Donabedian, and Claude Mutafian, 109-156. London, UK: Zed Books, 1994.

Nations Online Project. Political Map of Armenia. Map. Nation Online Project. Accessed on December 6, 2024. https://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/map/armenia_map.htm

News.AZ International “Monument to Armenian terrorist in Azerbaijan’s Khojavend dismantled (PHOTO).” Sept. 26, 2023. https://news.az/news/monument-to-armenian-terrorist-in-azerbaijans-khojavend-dismantled-photo.

Panorama. “Today is legendary commander Monte Melkonian's memorial day.” Jun. 12, 2023. https://www.panorama.am/en/news/2023/06/12/Monte-Melkonian/2850325.

Sullivan, Colleen. “Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia.” Encyclopedia Britannica, Aug. 3, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Armenian-Secret-Army-for-the-Liberation-of-Armenia.

Suny, Ronald Grigor. “Armenian Genocide.” Encyclopedia Britannica, Oct. 27, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/event/Armenian-Genocide/Genocide.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “The Armenian Genocide (1915-16): In Depth.” Holocaust Encyclopedia, accessed on November 30, 2024. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-armenian-genocide-1915-16-in-depth.

University of Minnesota College of Liberal Arts Holocaust and Genocide Studies. “Armenia.” Accessed on November 30, 2024. https://cla.umn.edu/chgs/holocaust-genocide-education/resource-guides/armenia.

Abigail McGown, “Azerbaijan’s Pressure on Nagorno-Karabakh: What to Know,” (Council on Foreign Relations), Sept. 14, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/azerbaijans-pressure-nagorno-karabakh-what-know.

“Monument to Armenian terrorist in Azerbaijan’s Khojavend dismantled (PHOTO).” (News.AZ International), 26 Sept. 2023, https://news.az/news/monument-to-armenian-terrorist-in-azerbaijans-khojavend-dismantled-photo

“Today is legendary commander Monte Melkonian's memorial day.” (Panorama), 12 Jun. 2023, https://www.panorama.am/en/news/2023/06/12/Monte-Melkonian/2850325.

Mark Arax, “COLUMN ONE: The Riddle of Monte Melkonian: Family and Friends Wonder How a Visalia Cub Scout with No Interest in His Roots Ended up as a Terrorist and Armenian War Martyr.” (Los Angeles Times), Oct. 9, 1993, www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-10-09-mn-43923-story.html.

Panorama, “Today is legendary commander Monte Melkonian's memorial day.”

Nations Online Project, Political Map of Armenia, Map, Nation Online Project, Accessed on December 6, 2024, https://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/map/armenia_map.htm.

“Armenia.” (University of Minnesota College of Liberal Arts Holocaust and Genocide Studies), accessed on November 30, 2024, https://cla.umn.edu/chgs/holocaust-genocide-education/resource-guides/armenia.

Ibid

Ronald Grigor Suny. “Armenian Genocide.” (Encyclopedia Britannica), Oct. 27, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/event/Armenian-Genocide/Genocide.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “The Armenian Genocide (1915-16): In Depth.” (Holocaust Encyclopedia), accessed on November 30, 2024, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-armenian-genocide-1915-16-in-depth.

Aleksey Aleksandrovich Mints and Ronald Grigor Suny. “Modern Armenia.” (Encyclopedia Britannica), Nov. 27, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/place/Armenia/Modern-Armenia.

Ibid

Ibid

Christoph Baumer. History of the Caucasus: Volume 2: in the Shadow of Great Powers. (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2023), 200, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ohiostate-ebooks/detail.action?docID=30747349.

Mark Malkasian, Gha-ra-bagh! The Emergence of the National Democratic Movement in Armenia, (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1996),22.

Ibid

Baumer, History of the Caucasus: Volume 2: in the Shadow of Great Powers, 205.

Ibid

Baumer, History of the Caucasus: Volume 2: in the Shadow of Great Powers, 206.

Malkasian, Gha-ra-bagh! The Emergence of the National Democratic Movement in Armenia, 23.

Ibid

Baumer, History of the Caucasus: Volume 2: in the Shadow of Great Powers, 206.

Baumer, History of the Caucasus: Volume 2: in the Shadow of Great Powers, 214.

Baumer, History of the Caucasus: Volume 2: in the Shadow of Great Powers, 213.

Aleksandrovich Mints and Grigor Suny, “Modern Armenia.”

Baumer, History of the Caucasus: Volume 2: in the Shadow of Great Powers, 213.

Malkasian, Gha-ra-bagh! The Emergence of the National Democratic Movement in Armenia, 23.

Ibid

Malkasian, Gha-ra-bagh! The Emergence of the National Democratic Movement in Armenia, 23-24.

Malkasian, Gha-ra-bagh! The Emergence of the National Democratic Movement in Armenia, 24.

Braumer History of the Caucasus: Volume 2: in the Shadow of Great Powers, 213; Malkasian, Gha-ra-bagh! The Emergence of the National Democratic Movement in Armenia, 23-24.

Markar Melkonian and Seta Melkonian. My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia (London: I.B. Tauris, 2005), 4-5.

Arax, “COLUMN ONE: The Riddle of Monte Melkonian: Family and Friends Wonder How a Visalia Cub Scout with No Interest in His Roots Ended up as a Terrorist and Armenian War Martyr.”

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 9.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 10.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 11-12.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 12.

Ibid

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 15-17.

Arax, “COLUMN ONE: The Riddle of Monte Melkonian: Family and Friends Wonder How a Visalia Cub Scout with No Interest in His Roots Ended up as a Terrorist and Armenian War Martyr.”

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 37-38.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 39.

Ministry of Defence of The Republic of Armenia, “Monte Melkonyan.” Ministry of Defence of The Republic of Armenia, accessed on November 30, 2024, https://www.mil.am/en/persons/64.

Arax, “COLUMN ONE: The Riddle of Monte Melkonian: Family and Friends Wonder How a Visalia Cub Scout with No Interest in His Roots Ended up as a Terrorist and Armenian War Martyr;” Colleen Sullivan. “Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia.” (Encyclopedia Britannica), Aug. 3, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Armenian-Secret-Army-for-the-Liberation-of-Armenia.

Directorate of Intelligence. The Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia: A Continuing International Threat. CIA-RDP85T00283R000400030009-2. CIA, Jan. 1, 1984, 1. https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP85T00283R000400030009-2.pdf.

Arax, “COLUMN ONE: The Riddle of Monte Melkonian: Family and Friends Wonder How a Visalia Cub Scout with No Interest in His Roots Ended up as a Terrorist and Armenian War Martyr”; Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 83-84, 97.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 83.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 84.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 85.

Arax, “COLUMN ONE: The Riddle of Monte Melkonian: Family and Friends Wonder How a Visalia Cub Scout with No Interest in His Roots Ended up as a Terrorist and Armenian War Martyr.”

Ibid

Sullivan, “Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia.”

Directorate of Intelligence. The Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia: A Continuing International Threat, 3; Sullivan, Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia.”

Arax, “COLUMN ONE: The Riddle of Monte Melkonian: Family and Friends Wonder How a Visalia Cub Scout with No Interest in His Roots Ended up as a Terrorist and Armenian War Martyr.”

Ibid

“Melkonian Monte.” (Institute for Armenian Studies of Yerevan State University: History of Armenia), accessed on November 30, 2024. http://www.historyofarmenia-am.armin.am/en/Encyclopedia_of_armenian_history_Monte_Melqonyan.

Arax, “COLUMN ONE: The Riddle of Monte Melkonian: Family and Friends Wonder How a Visalia Cub Scout with No Interest in His Roots Ended up as a Terrorist and Armenian War Martyr.”

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 167, 169.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 171-175.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 177.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 176-178.

[Monte Melkonian]. Accessed on December 6, 2024, Photograph, 100 Lives, https://legacy.auroraprize.com/en/armenia/detail/10162/monte- %25E2%2580%259Cavo%25E2%2580%259D-melkonian%252C- commander-of-artsakh-war-for-independence-

Malkasian, Gha-ra-bagh! The Emergence of the National Democratic Movement in Armenia, 28.

Claude Mutafian, “Karabagh In the Twentieth Century,” in The Caucasian Knot: The History And Geopolitics of Nagorno-Karabagh, by Levon Chorbajian, Patrick Donabedian, and Claude Mutafian, 109-156. (London, UK: Zed Books, 1994), 149.

Mutafian, “Karabagh In the Twentieth Century,” 150-154.

Mutafian, “Karabagh In the Twentieth Century,” 155.

Mutafian, “Karabagh In the Twentieth Century,” 155-157.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 193-194.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 194.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 184; Institute for Armenian Studies of Yerevan State University: History of Armenia, “Melkonian Monte.”

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 185.

Ibid

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 195.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 210-211.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 211-212.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 213.

McGuinness, Damien. “Nagorno-Karabakh: Remembering the victims of Khojaly.” BBC News, Feb. 27, 2012, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-17179904.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 212.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 214.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 227, 234.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 234-235.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 243-244.

Melkonian and Melkonian, My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia, 249.

Edik Baghdasaryan, “June 12, 1993 – Monte Melkonian Met Death On the Battlefield.” (Hetq), Jun. 12, 2012, https://hetq.am/en/article/2045.

Nikolay Hovhannisyan, “Monte Melkonian: A talented scholar and defender of Karabakh's self-determination.” (ARMENPRESS), May 21, 2014, https://armenpress.am/en/article/762659.

HovoYerevan, Monte Melkonian’s Funeral, 1993, Photograph, Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/65903724@N04/8666330421/.

“The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: A Visual Explainer.” (International Crisis Group), Sept. 16, 2023. https://www.crisisgroup.org/content/nagorno-karabakh-conflict-visual-explainer.

McGown, “Azerbaijan’s Pressure on Nagorno-Karabakh: What to Know.”

Ibid

Mathieu Droin, Tina Dolbaia, and Abigail Edwards. “A Renewed Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Reading Between the Front Lines.” (CSIS), Sept. 22, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/renewed-nagorno-karabakh-conflict-reading-between-front-lines.

Luke Harding, “‘They want us to die in the streets’: inside the Nagorno-Karabakh blockade.” (The Guardian), Aug. 22, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/aug/22/inside-nagorno-karabakh-blockade-armenia-azerbaijan.

Ibid

McGown, “Azerbaijan’s Pressure on Nagorno-Karabakh: What to Know;” Christian Edwards, “Nagorno-Karabakh will cease to exist from next year. How did this happen?” (CNN), Sept. 28, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/2023/09/28/europe/nagorno-karabakh-officially-dissolve-intl/index.html.

Edwards, “Nagorno-Karabakh will cease to exist from next year. How did this happen?”

Associated Press. “Almost all ethnic Armenians have left Nagorno-Karabakh.” (The Guardian), Sept. 30, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/sep/30/almost-all-ethnic-armenians-have-left-nagorno-karabakh-azerbaijan.