During Fumio Kishida’s prime ministership, the Japanese government increased defense spending to address the “greatest trial since the end of World War II.”1 These trials include countering Chinese aggression over South-East Asian sea routes, disputes over territories such as the Senkaku Islands, and the regional implications from Russian aggression in Ukraine. In the domestic sphere, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) faces increasing domestic opposition due to party mismanagement and corruption scandals. At the same time, the Japanese business community, and particularly its defense industry, is working with the government to re-align and begin the process of disconnecting supply chains tied to national defense from potentially adversarial governments such as China. Furthermore, they are working to contract weapon systems–such as US Tomahawk cruise missiles – prohibited less than five years ago under Article 9 of the Japanese constitution.

This article evaluates Japanese perception of regional security threats, and how they influence Japanese Self Defense Force (JSDF) and Japanese Self Maritime Self-Defense Force (JSMDF) budgeting, procurement, and force structure as a result. It also explores how Japan views its existing alliances with principal Pacific powers such as the United States, and concepts such as interoperability with the United States and the wider NATO organization.

Security Environment

Two relevant blocs of states interact with Japanese interests in East Asia: China-aligned states and US-aligned states.

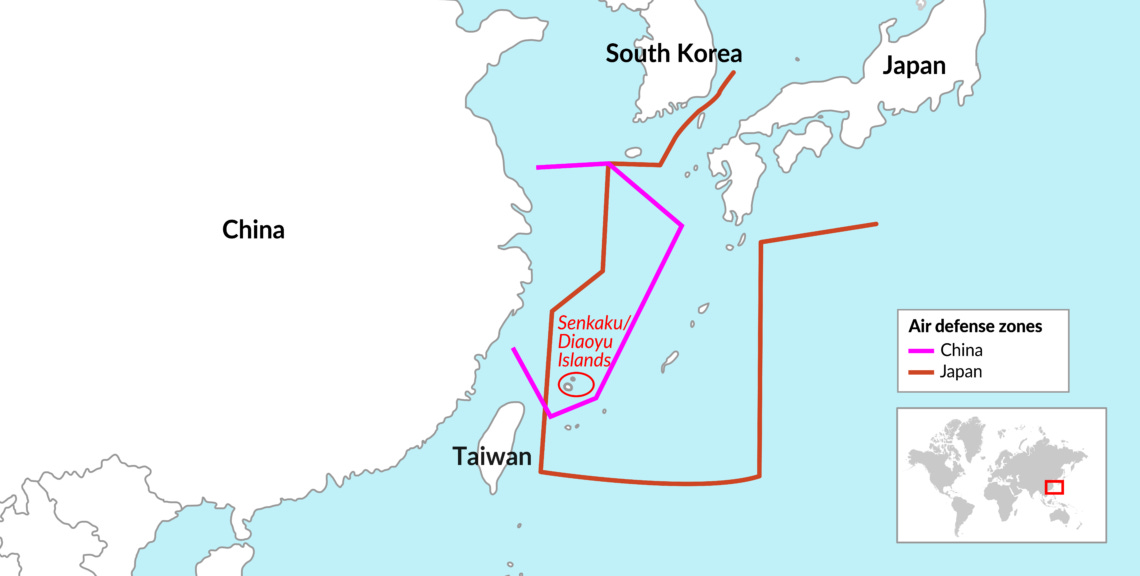

Figure 1. China, Taiwan and Japan all claim these islands as their territory. The danger of an intended or accidental collision between the three states’ warships and aircraft has grown since China intensified its intrusions in 2020. Accessed on January 25, 2025. Geopolitical Intelligence Services, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/senkaku-islands/.2

China's bloc, including Russia and North Korea, pose the greatest threat to Japanese security and national interests in the Pacific. China is involved in controversies over sea lines of communication within international shipping lanes as well as the dispute over the Senkaku Islands. The Senkakus illuminate a microcosm of the character and aspects that illustrate Japanese and Chinese disputes. In 1885, the Japanese government integrated the Senkaku Islands into the Okinawa Prefecture following a set of surveys considering the territory terra nullius – uninhabited by any other state. Japan’s claim went uncontested until the 1970s when a UN survey discovered a potentially large reserve of hydrocarbon and oil resources off the Senkakus. In response to the UN’s discovery, China began to contest Japanese claims to the islands by citing historical records claiming the Senkakus to be a part of historical Taiwan. Multiple key regional issues are all found in the Senkaku dispute: competition over limited resources— particularly energy resources—and what government gains sovereignty over international maritime claims and sea lines of communication. By extension, the ability of Japan and its allies to move commercial and military shipping through any of the routes feeding through contested waters near the Senkaku Islands is intertwined with these issues. Other states such as the Philippines also deal with constant Chinese incursions and grey-zone tactics in similarly contested island chains.3 Taiwan is another major security risk, which Russian actions in Ukraine have brought into the forefront. The Japanese government’s “Defense of Japan” pamphlet directly cites the Russia-Ukraine conflict as potentially implicating conflict in the Pacific over contested borders.4

In other words, Japan believes that international inaction in Ukraine could lead to inaction in a cross-channel invasion of Taiwan. If China annexes Taiwan, the Japanese home islands are in worse proximity to Chinese military air installations and missiles. Additionally, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS,)Chinese annexation of Taiwan would threaten 28.82% of all Japanese international shipping. Disruptions in shipping capacity would have untold consequences on Japan. Aside from potential food insecurity and a sharp rise in the price of food imports, A Taiwan Strait closure would threaten international shipping as well. Due to Japan’s reliance on the international market, market disruptions would reach Japan’s shores as well.

Many US-aligned states, such as the Philippines and Australia, face the same security challenges. Freedom of navigation and contested maritime claims are both future seeds of cooperation between Japan and the nations within the Indo-Pacific that share these issues. However, US alignment does not automatically imply Japanese alignment. The United States is the locus of strategic decision-making for most Indo-Pacific powers, not Japan. In recent years, Japan issued co-operative overtures towards NATO organs. For instance, Japan signed the ‘Security of Information and Material’ agreement in 2017, signaling that Japan recognizes their own military is not enough to deter aggression.5 This phenomenon signals a focus on interoperability—the ability for the JSDF and JSMDF to conduct combat operations with allied militaries—as a critical focal point in Japanese strategy within the wider NATO organization. For example, Japan contracts much of its equipment from premier militaries such as the United States which gives the Japanese military experience in both using and maintaining American equipment. As the strategic center shifts away from Japan, it is the most sensible and politically tenable choice to prioritize air defense and counter-strike capabilities over long-range expeditionary and amphibious operations. These force structure changes will work in tandem with allied military forces to produce well-rounded defensive capabilities in the Pacific.

Japanese Defense Initiatives

The JSDF has already made multiple decisions in defense reform and force re-structuring. The main aim is to build interoperability with US weapons platforms. For example, the first stage of refitting the Izumo and the Kaga–two out of four of Japan’s Helicopter Destroyers– was completed in March of 2024. The modifications intend to officially re-designate them as Light Carriers capable of using the F-35B.6 Many pundits and commentators pointed out the dubious designation of ‘Helicopter Destroyer’ by the JSDF, critical of its legality as well as Japan’s moral imperative against its imperial past. These weapons systems and designs demonstrate Japan’s changing concept of domestic security. One design decision already exists in the Izumo-class - heat-resistant paint on the decks that would better withstand vertical take-off and landing aircraft (VTOL) such as the F-35. China accused the Abe administration of re-building an offensive carrier arm, a charge carrying historical and emotional connotations in many Asian countries. The Izumo-class illuminates Japanese security fears over the contested Senkaku Islands and regional balancing—only the world’s pre-eminent militaries support carriers. Carriers are a weapons platform with a storied history going back to the Second World War. They carry both military and political implications by their deployment. By deploying carriers, a navy demonstrates that it wants to project power past its own maritime borders and conduct naval operations supported by carrier-based aircraft. Through focusing on developing this capability, Japan will be more flexibly able to strike anywhere in the Pacific, independent of allied carrier support.

Figure 2, Japan Maritime Self Defense Force (JSMDF) Izumo-Class. Photograph by Asika Collins, October 26, 2020. US Navy, https://nara.getarchive.net/media/japan-maritime-self-defense-force-jmsdf-izumo-class-7bc75d.7

The Tomahawk deal—announced in mid-January of 2024–provides insights into Japanese security-planning. In 2013, the Obama administration rejected Japanese overtures in procuring US Tomahawks. Eleven years later, the Biden administration revisited the issue in a newly negotiated deal.8 This example further proves Japan’s increasing willingness to invest in new weapon systems, as well as a significant departure from foreign policy stances taken by previous US presidents. The Japanese Ministry of Defense negotiated the procurement of 200 Block IV Tomahawks, 200 Block V Tomahawks and 14 Tactical Tomahawk Weapon Control Systems, along with the requisite auxiliary equipment and personnel to maintain them.9 Initially set to be delivered in 2026, then Japanese Defense Minister Minoru Kihara moved the delivery timeline up a year “because of the increasingly severe security environment.”10 This coincides with a widespread pattern of grey-zone tactics around contested maritime borders, particularly while the deal was being negotiated. The Tomahawks will be deployed on the JSDF destroyer fleet and Japanese military bases in and around the Japanese Home Islands. The Tomahawks illustrate how the regional security environment directly contributes to Japanese security policy. Integrating US equipment and expertise into the JSDF indicates a closer alignment for the two countries’ militaries. Additionally, it demonstrates the inadequacy of the Japanese defense industry to supply the necessary equipment. Cruise missiles already had a place within Japanese strategy and doctrine. The recent Tomahawk deal and Japan’s drive to produce these weapons domestically shows that Japan wants to deter potential threats by making the cost of attacking too great to justify the investment. Full modernization emphasizes regional challenges while maintaining a politically acceptable level of defense capability for the Japanese government. Aegis defense systems, home-developed stand-off missiles, and naval expansion alongside the Izumo-class refits all conform to Japan’s emphasis on counter-strike capability.

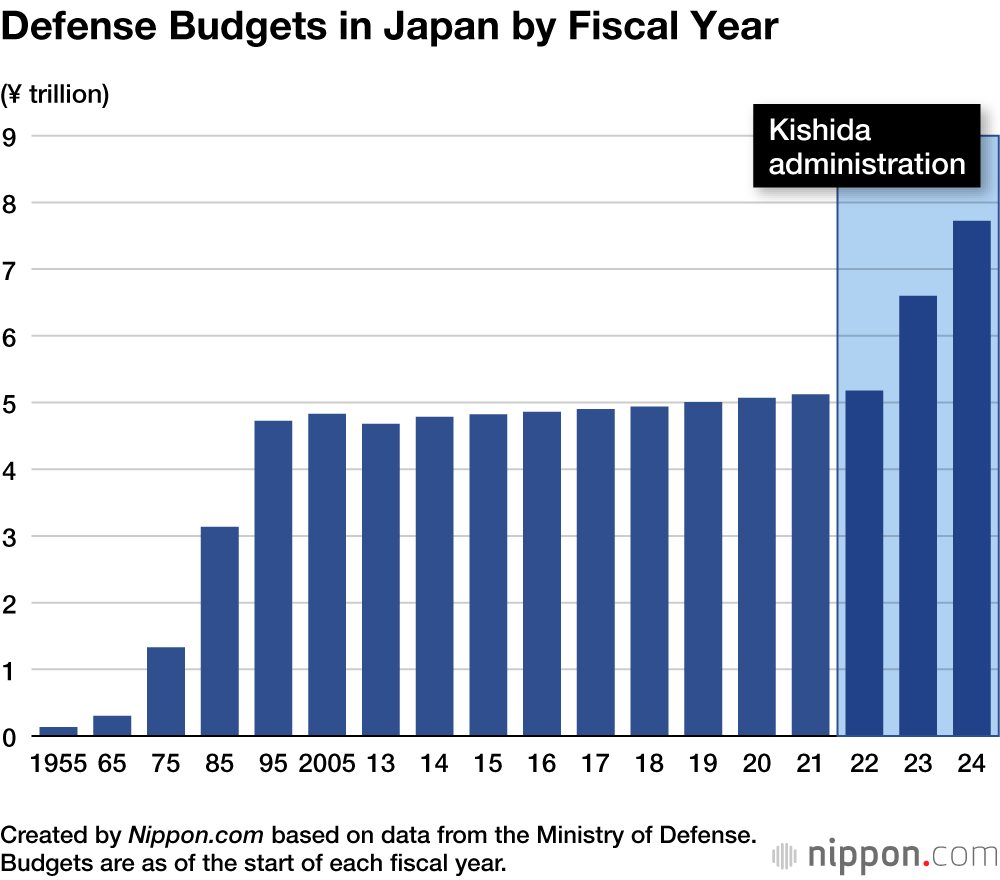

Figure 3. Defense Budgets in Japan by Fiscal Year. Chart by Nippon.com, 2024. Nippon.com, https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-data/h02121/japan%E2%80%99s-defense-budget-rising-toward-nato-target-of-2-of-gdp.html.11

Trends in Japan’s national defense spending can illuminate trends in Japanese national security development. In late 2023, the Kishida Fumio government approved 7.95 trillion yen ($55.9 billion USD) for the Defense Buildup Program’s second year. His justification rested on claiming that East Asia was in “the most severe and complex security environment since the end of World War II.”12 According to the World Bank, this accounts for 1.1% of Japan’s GDP.13 Within the past two decades, Japanese defense spending has floated around 1% of total GDP. In the period of 2012 to 2019, the percentage increased cumulatively only by 0.03%. The lowest point within that period occurred in 2017 at 0.91% of GDP.14 In comparison, 1.1% is a significant and rapid increase in defense spending for the Japanese government. This indicates Japan seeing the direct utility in investing in these initiatives, rather than towing the western line internationally in rhetoric towards China and Russia. It is acknowledging them as threats, and is shifting its spending accordingly to meet these threats. For a power still nominally constrained by an anti-war clause in their constitution, this increase in spending signifies a massive shift in both the Japanese government’s willingness and ability to reform its military in the long-term to address its newfound security realities.

Conclusions

The future of East Asian and Southeast Asia rests on the balance of power between China and Japan. The Japanese government did not make the decision to militarize lightly, due to its commitment to peace and history with war. The shift to pragmatic concerns signals Japan’s belief and need to be a credible threat. Without this deterrence, an increasingly aggressive China would threaten Japanese trade. Furthermore, it would cause short-term economic losses, and force re-alignment to China long-term, which would have its own policy implications for the United States and internationally. Japan enjoys a privileged position within the United States security blanket and integration with the world economy; it has ample reason to protect these commitments through increased cooperation with the West.

Re-armament will continue to be a thorny issue both internationally and domestically. Furthermore, the newly inaugurated Trump administration may pursue a policy of retrenchment with regards to international alliances. The recently elected Shigeri Ishiba is already pursuing negotiations with the United States to maintain their force presence, warning against the dangers of a ‘power vacuum’ in the Pacific. Prime Minister Ishiba announced his intentions in Parliament, encouraging his government to further pursue positive relations with the United States.15 President Trump’s increasingly demanding rhetoric for United States allies to “pay their fair share” could have the ironic effect of pushing the Japanese government to prioritize defense appropriations to maintain security ties.16 Other NATO allies are already getting into political altercations over the 5% NATO spending target, and time will tell if these concerns will ultimately be unfounded in Japan’s case. For Japan, the first two years of the Trump administration will determine how it will continue to pursue re-armament. Should the US stay true to its previous commitments, Japan will have no reason to deviate from its current course, unless a border altercation escalates into immediate conflict. If the Trump administration believes the Japanese government is not committed enough to its spending targets and reneges on its commitments, multiple scenarios can be considered. The Japanese government may choose to accelerate armament further and independently negotiate security arrangements with other Pacific states such as Taiwan, the Philippines and Australia. The less likely option is Japan decelerating armament and seeking detente with the Chinese government. The Constitutional Democratic Party, whose coalition is currently the majority in the Japanese Parliament, has positioned itself resolutely on re-armament and its commitment to the United States-Japan partnership. It is unlikely most politicians in the Japanese government will swear off cooperation with the US altogether in favor of cooperation with the Chinese government. In either case, the Trump administration will heavily determine Japanese defense policy going forward.

Bibliography

Collins, Asika. Japan Maritime Self Defense Force (JSMDF) Izumo-Class. October 26, 2020. Photograph. US Navy. https://nara.getarchive.net/media/japan-maritime-self-defense-force-jmsdf-izumo-class-7bc75d.

Geopolitical Intelligence Services. China, Taiwan and Japan all claim these islands as their territory. The danger of an intended or accidental collision between the three states’ warships and aircraft has grown since China intensified its intrusions in 2020. Image. Geopolitical Intelligence Services. https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/senkaku-islands/.

Kato, Hiroaki. “Japan's Long-Range Strike Capability was Not Sudden.” The Diplomat, Dec. 21, 2022. https://thediplomat.com/2022/12/japans-long-range-strike-capability-decision-was-not-sudden/.

Kosuke, Takahashi. “Japan Approves 16.5% Increase in Defense Spending for FY2024.” The Diplomat, Dec. 22, 2023. https://thediplomat.com/2023/12/japan-approves-16-5-increase-in-defense-spending-for-fy2024/.

Kosuke, Takahashi. “Japan Completes First Stage of JS Kaga Modification to Operate F-35B.” Naval News, Apr. 8, 2024. https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2024/04/japan-completes-first-stage-of-js-kaga-modification-to-operate-f-35b/.

Mahadzir, Dzirhan. “Japan Signs Deal for 400 Tomahawk Land Missiles.” USNI News, Jan. 18, 2024. https://news.usni.org/2024/01/18/japan-signs-deal-for-400-tomahawk-land-attack-missiles.

Ministry of Defense. “2024 Defense of Japan Pamphlet.” Government of Japan, July 12, 2024, https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/25088868/doj2024_en_full-1.pdf.

Nippon.com. Defense Budgets in Japan by Fiscal Year. Chart. Nippon.com. https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-data/h02121/japan%E2%80%99s-defense-budget-rising-toward-nato-target-of-2-of-gdp.html.

O’Neill, Aaron. “Japan: Ratio of military spending to gross domestic product (GDP) from 2012 to 2022.” Statista, Nov. 4, 2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/810444/ratio-of-military-expenditure-to-gross-domestic-product-gdp-japan/.

P. Funaiole, Matthew, and Brian Hart, David Peng, Bonny Lin, Jasper Verschuur, “Crossroads of Commerce: How the Taiwan Strait Propels the Global Economy.” Center for Strategic and International Studies, Oct. 10, 2024 https://features.csis.orgchinapower/china-taiwan-strait-trade/.

Sato, Yoichiro and Astha Chadha. “Understanding the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands Dispute: Diplomatic, Legal, and Strategic Contexts,” E-International Relations, June 23, 2022. https://www.e-ir.info/2022/06/23/understanding-the-senkaku-diaoyu-islands-di spute-diplomatic-legal-and-strategic-contexts/.

Scislowska, Monica and Vanessa Gera. “European defense heavyweights say meeting Trump’s military spending target won’t be easy.” Associated Press, Jan. 13, 2025. https://apnews.com/article/poland-britain-france-italy-germany-defense-809faa044ff6d4f913fc2647cfa7d454.

Wang, Amber. “China, Philippines trade blame over run-in near contested Spratlys reef in South China Sea.” South China Morning Post, Dec. 2, 2024. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3289046/china-philippines-trade-blame-over-run-near-contested-spratlys-reef-south-china-sea.

W. Hornung, Jeffery. “Japan-NATO ties: For What End?” RAND Corporation, July 8, 2024. https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2024/07/japan-nato-ties-for-what-end.html

World Bank. “GDP (constant 2015 US$) - Japan” World Bank, accessed Nov. 20, 2024, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD?locations=JP.

Yamaguchi, Mari. “Japan’s leader says he’s preparing for tough negotiations with Trump on maintaining US presence.” Associated Press, Jan. 24, 2025. https://apnews.com/article/japan-us-ishiba-trump-policy-speech-513fd50d851c2818a39dc323aaca10ab.

Japanese Ministry of Defense, "2024 Defense of Japan.” (Government of Japan, July 12, 2024). https://www.mod.go.jp/en/publ/w_paper/index.html.

China, Taiwan and Japan all claim these islands as their territory. The danger of an intended or accidental collision between the three states’ warships and aircraft has grown since China intensified its intrusions in 2020, Image, Geopolitical Intelligence Services, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/senkaku-islands/.

Amber Wang, “China, Philippines trade blame over run-in near contested Spratlys reef in South China Sea.” (South China Morning Post, Dec 2 2024,) https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3289046/china-philippines-trade-blame-over-run-near-contested-spratlys-reef-south-china-sea.

Japanese Ministry of Defense, "Defense of Japan 2024,” 39.

Jeffery W. Hornung, “Japan-NATO Ties: For What End?” (RAND, Jul 8, 2024). https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2024/07/japan-nato-ties-for-what-end.html.

Kosuke Takahashi, “Japan Completes First Stage of JS Kaga Modification to Operate F-35B.” (Naval News, Apr. 8 2024). https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2024/04/japan-completes-first-stage-of-js-kaga-modification-to-operate-f-35b/.

Asika Collins, Japan Maritime Self Defense Force (JSMDF) Izumo-Class, October 26, 2020, photograph, US Navy, https://nara.getarchive.net/media/japan-maritime-self-defense-force-jmsdf-izumo-class-7bc75d.

Hiroaki Kato, ”Japan’ Long-Range Strike Capability was Not Sudden.” (The Diplomat, Dec 21 2022). https://thediplomat.com/2022/12/japans-long-range-strike-capability-decision-was-not-sudden/.

Dzirhan Madahzir, “Japan Signs Deal for 400 Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles.” (U.S Naval Institute News, Jan 18 2024). https://news.usni.org/2024/01/18/japan-signs-deal-for-400-tomahawk-land-attack-missiles.

Mahadzir, “Japan Signs Deal for 400 Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles.”

Defense Budgets in Japan by Fiscal Year, 2024, chart, Nippon.com, https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-data/h02121/japan%E2%80%99s-defense-budget-rising-toward-nato-target-of-2-of-gdp.html.

Kosuke, ”Japan Approves 16.5% Increase in Defense Spending in FY2024.”

“GDP (constant 2015 US$) - Japan.” (World Bank, accessed Nov 20 2024). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD?locations=JP.

Aaron O’Neil. “Japan: Ratio of military spending to gross domestic product (GDP) from 2012 to 2022.” (Statista, Nov. 4, 2024). https://www.statista.com/statistics/810444/ratio-of-military-expenditure-to-gross-domestic-product-gdp-japan/.

Mari Yamaguchi, “Japan’s leader says he’s preparing for tough negotiations with Trump on maintaining US presence.” (Associated Press, Jan 24 2025). https://apnews.com/article/japan-us-ishiba-trump-policy-speech-513fd50d851c2818a39dc323aaca10ab.

Monia Scislowska and Vanessa Gera, “European defense heavyweights say meeting Trump’s military spending target won’t be easy.” (Associated Press, Jan 13, 2025). https://apnews.com/article/poland-britain-france-italy-germany-defense-809faa044ff6d4f913fc2647cfa7d454.