Haiti is a country known for its instability and struggles. Its history of colonization, occupation, coups, and natural disasters has hindered the country’s development. The colony gained its independence from French rule due to a slave revolt. Haiti disrupted the order of things as the world’s first Black republic and was a beacon of hope for slaves in the U.S. and Black people throughout the diaspora. However, the colony that once enjoyed vast wealth is now the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. Most Haitians live below the World Bank poverty line.1 The country also heavily relies on foreign aid for development assistance and relief. So, what has changed and contributed to the country’s present issues? Why has security in Haiti devolved to such an extent?

The tiny nation has had its capital stolen from it to such a degree that it’s been crippling. Exploitation by Western powers, namely France and the United States, is responsible for much of Haiti’s troubles. These two countries especially have interfered with Haiti, undermining its development at every turn. For example, the U.S. bears the brunt of the responsibility for Haiti’s political instability given that American administrations have installed the most corrupt Haitian presidents, and that the U.S. also consistently meddles in their elections.2 The French are to blame for Haiti’s economic woes as the French government overburdened the tiny nation with debt obligations immediately after it gained independence and before the country was able to establish itself. With this in mind, if we wish to understand why Haiti faces its current predicament, we must critically examine the nation’s past. This article will detail this past, from its independence to the present day, touching upon the compounded effects of Haiti’s indebtedness, political turmoil, and the devastating 2010 earthquake from which the country has yet to recover fully. Readers will gather that while Haiti has been independent since 1804, one can argue that the country is still not free from foreign meddling and neocolonialism.

BACKGROUND

Haiti is on the island of Hispaniola which it shares with the Dominican Republic. Before European contact, the indigenous people on the island were the Taino people. They were killed in large numbers by diseases brought over by the Spanish in 1492. The French later massacred the few that remained. The Europeans replaced them with Africans they captured as slaves, the ancestors of present-day Haitians. The French named the western part of the island, where the country is now situated, Santo Domingue. Santo Domingue was France’s richest colony throughout the 18th century and one of the wealthiest in the Americas. It represented 50% of France’s economic output due to the wealth extracted from plantation slavery. For reference, Santo Domingue’s valuable resources (sugar, coffee, cotton) created more wealth for France than all the 13 colonies combined did for Great Britain.3

HAITIAN REVOLUTION

From 1789 through 1799, the French Revolution weakened France and made them vulnerable to a slave revolt in their colony. Slaves in Santo Domingue were the overwhelming majority in the colony. They outnumbered their colonial officers 10-1.4 The slaves took inspiration from the revolution in France and made attempts to rebel. Former slave Toussaint L’Ouverture led the Haitian Revolution from 1791 until 1803. Under his leadership, rebels took parts of the colony and defeated French forces in numerous battles. After achieving control of Santo Domingue, L'Ouverture abolished slavery and declared himself Governor-General of all of Hispaniola. In 1802, Napoleon, Emperor of France, ordered his troops to capture L’Ouverture and reestablish slavery and French dominion. His forces seized L’Ouverture and took him to prison in France, where he died. Jean-Jacques Dessalines, a general under L’Ouverture, took over the rebellion’s efforts and defeated the French in battle for the last time in 1803. Dessalines declared the nation independent in 1804 and renamed it Haiti. As the first Black republic, Haiti was a source of inspiration for enslaved Black Americans who wanted their freedom. Despite becoming sovereign in 1804, the United States did not recognize Haiti’s independence until 1862 as leaders felt the new country’s existence threatened the institution of slavery in the States.5

Life in the newly independent Haiti was not ideal or inspiring. Soon after independence, the elite in Haiti (mulattos and former plantation owners) formed a government centered on a strong military. They sought to protect themselves from external hostility coming from the French and Americans. The elite prioritized a plantation-led export economy based on serfdom to support their new state in lieu of building an egalitarian, democratic society. Though the slave trade had stopped, forced labor continued to be used to make the country economically viable. The elite became corrupt to maintain their power over the majority.6 This state of affairs has persisted to the detriment of everyone.

DEBT SLAVERY

The French were aggrieved at losing their profitable colony and refused to take a loss on their investment. Former colonial officers in France, who had been the plantation owners in Haiti, felt slavery’s end diminished their ability to acquire wealth, and therefore, they were entitled to compensation. The French demanded that Haiti pay them 150 million francs of “reparations” or face an invasion.7 A catch-22 faced Haiti, which had to either pay the debt to France to remain free or refuse and lose its sovereignty in an invasion. Because of this, France coerced Haiti into paying them back for over a century with money that could have otherwise gone to development. These debt payments went on from 1825 to 1947.8 The Haitian government produced cash crops to pay this debt rather than for food to sustain its population. Haiti even had to take out loans from American banks to pay their debt and then owed more money to these institutions.9 Much of Haiti’s wealth went back to France, crippling the country financially. These reparations would be equal to $21 Billion in dollars and took as much as 80% of the country’s revenue away from other purposes.10

AMERICAN OCCUPATION, INTERFERENCE, AND ELECTIONS

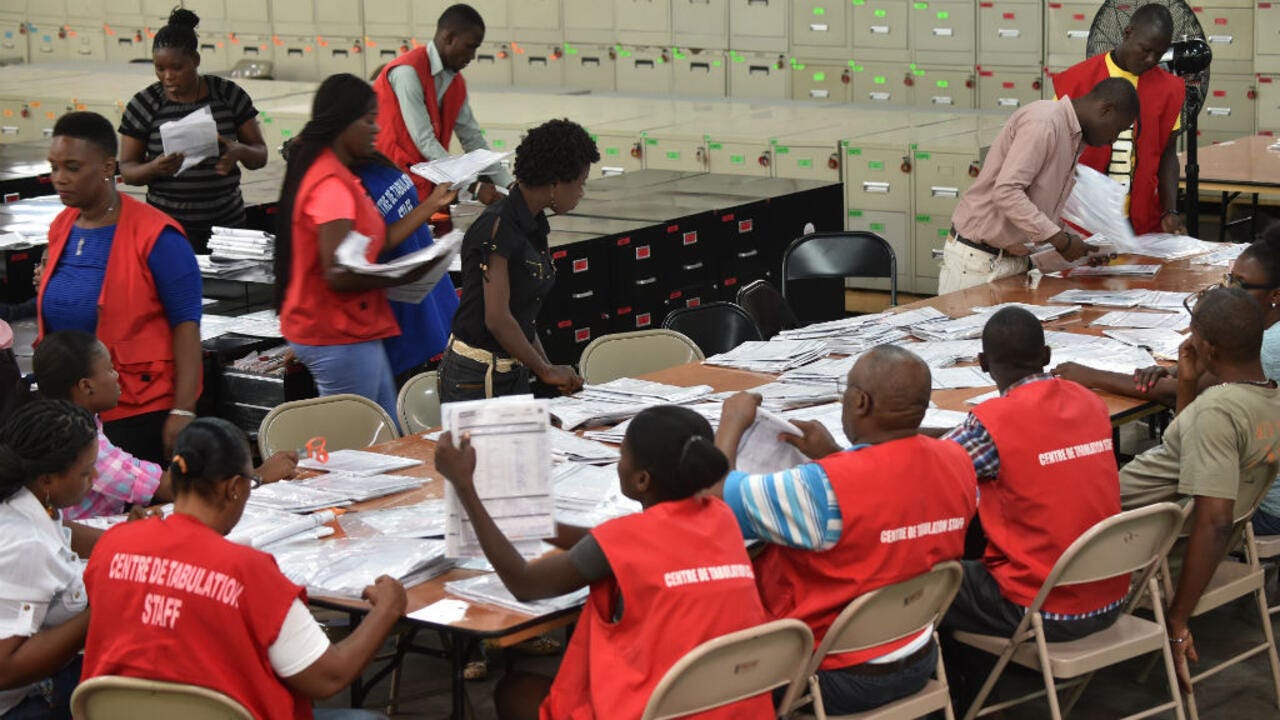

Image 1. Hector Retamal, Polling center employees in Port-au-Prince tally votes November 21, 2016 one day after the Haitian presidential and legislative elections, November 22, 2016, photograph, AFP, Port-au-Prince, Haiti, https://www.france24.com/en/20161122-haiti-rival-parties-claim-victory-presidential-election.

Corrupt, greedy, and repressive leaders have kept the country from progressing. The government is never stable because of frequent assassinations and coups. For example, Haiti once had seven presidents within a five-year period.11 The U.S. has played a significant role in keeping the country down. For about twenty years in the early 20th century (1915-1934), Haiti was militarily occupied by U.S. forces under the guise of installing democracy. They instituted martial law and a pro-U.S. puppet government.12 The Americans took advantage of a weak Haiti, stealing gold from its national bank and exerting control over the country through domination of its financial institutions. The bank now known as CitiBank took control over Haiti’s national bank from the French in 1922. From this point on, Haiti’s debt was now owed to U.S. institutions. American banks extracted billions in debt repayments from the struggling nation until 1947.13 The capital Haiti desperately needed to develop itself was robbed from them.

U.S. interference continued throughout the 20th century. During the Cold War, America was worried communist sentiment would gain traction in Haiti as it was growing in Cuba. As such, they backed fascist dictator Francois Duvalier in 1957, also known as Papa Doc, who would suppress the population that might have found communist sentiments favorable.14 The next year, Fidel Castro tried to overthrow Duvalier to aid the spread of Communism. However, Duvalier remained in power and had the space to be more critical of the U.S. because he was still very valuable to them as an anti-Communist asset. He even went as far as to call for a moratorium on debt payments to the American banks. Shortly thereafter, JFK ordered a CIA coup in Haiti that ultimately failed to remove Duvalier from power.

Duvalier, emboldened by resisting overthrow, declared himself president for life. During his rule, he had political opponents exiled, tortured, or murdered. He misappropriated millions of dollars of international aid from the United States. He even called sham elections where he was the only candidate and the ballots were pre-marked. A rigged constitutional referendum later gave him absolute rule and the right to choose his successor.15 Duvalier decided his son would succeed him after his death. America had little control over him and disregarded his authoritarian rule. The U.S. tolerated him as long as he was ardently anti-Communist. Duvalier ruled for fourteen years, from 1957 to 1971, until his death.

His son, Jean-Claude Duvalier, also known as Baby Doc, took his place. Duvalier assumed office at 19, becoming the world’s youngest non-royal head of state. He tempered tensions with the U.S. so that Haiti could receive more foreign investment (aid). He was beloved by the American establishment and was allowed to stay in power for 15 years from 1971–1986. In 1986, a rebellion by the Haitian people over their worsening economic conditions came to a head. Eventually, the injustices and repression in Duvalier’s government made it untenable and undesirable for the U.S. to continue its allegiance and be complicit. There were worries in Reagan’s administration that Haiti’s unrest could lead it to fall to Communist Cuba.16 Reagan pressured Duvalier to leave power, but he refused. As a result, the U.S. cut aid to Haiti and supported uprisings against him. Duvalier fled to France on a U.S. Air Force plane in 1986, living in self-imposed exile. In his absence, the U.S. financed the Haitian military regime as the country’s main political force and reinstated aid to Haiti.

After Jean-Claude (Baby Doc) Duvalier’s ousting, the CIA created, funded, and trained Haiti’s Service d’Intelligence National (SIN) agency. This intelligence agency, which is no longer in existence, manipulated Haitian elections and selected the leaders the U.S. would prefer, The SIN also secretly paid to influence these elections.17 During election time in 1987, the SIN killed up to 300 Haitian civilians who were attempting to vote, leading to that year’s elections being suspended. SIN officials had been operating at the behest of the military regime which wanted the elections canceled so they could remain in power. The CIA faced opposition from the U.S. Senate for this election meddling and was ordered to stop, to no avail. From 1986-1991, the SIN murdered thousands of leftists and supporters of democracy.18

POLITICAL INSTABILITY

Image 2. Robert Nickelsberg, Close-up of Haitian president-elect Jean-Bertrand Aristide as he holds a press conference after winning the election, Port-au-Prince, Haiti, November 27, 2000, photograph, Getty Images, Port-au-Prince, Haiti, https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/close-up-of-haitian-president-elect-jean-bertrand-aristide-news-photo/1490204865.

A new leader, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, campaigns on ending military-enforced rigged elections, American meddling, and foreign neocolonialism and wins in the first free election held in Haiti in 1990 against candidates bought and paid for by America.19 During his time in office, he tackled corruption and helped exploited and underpaid workers. Bush Sr. worried Aristide was Communist-leaning and a threat to America. The U.S. exploited the resentment the Haitian upper class felt at Aristide’s aid to the poor to help remove him from power.20

The CIA and USAID worked to ruin Aristide’s reputation and oust him. After 7 months, Aristide was deposed by the military and exiled. The CIA then chose a new symbolic prime minister. A military terror squad tortured supporters of Aristide. The CIA reportedly paid this group, called FRAPH (Front for the Advancement and Progress of Haiti).21 A crisis ensued, and desperate Haitians even took to the sea to try to get to the U.S. for safety. Domestically, protests grew that threatened the American-backed military regime’s power.

The U.S. led Operation Uphold Democracy (1994-95) to remove the military regime they had installed. Key Haitian military officers were paid to leave the country and keep quiet about their connections to the U.S. America confiscated and hid roughly 160,000 pages of documents that linked them to the military junta. The U.S. sought to erase their ties to the junta to conceal the fact that they had installed them from the international media. The U.S. purported that their efforts to remove the military regime government were to establish democracy in the country.22 Aristide was restored as President by America from 1994-1996, required to submit to the wishes of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. President Clinton and Aristide agreed to such conditions to keep the peace in Haiti, which Aristide later admitted was more for America’s interests of hegemony than Haiti’s.23 Pressure from America backed Aristide into a corner with no option but to relent.

The U.S. was not sincerely committed to establishing democracy but rather committed to the facade of democracy. Aristide was deposed again in 1996 for creating a political party deemed too far left. For the next few years, a handful of minor interim presidents were in power. In 2000, the people popularly elected Aristide for the third time, to the chagrin of the Western establishment. In response, the U.S., France, and the European Union (EU) stopped all loans and humanitarian aid to Haiti to undermine him.

In 2003, Aristide advocated for France to compensate Haiti for the forced independence debt. He said the amount of restitution, with interest and inflation in mind, totaled $21 Billion.24 This upset France, who sent warnings to Aristide to flee after threatening to overthrow him again. Ambassadors from France and America visited Aristide at the President’s residence demanding he resign, relaying that military forces from America and Canada were prepared to invade the capital of Port-au-Prince. They made him deliver a press conference to announce his resignation and then took him to the airport to board an American plane, after which he was exiled. This 2004 coup removed Aristide from power for the third and final time.

The American military, French, and Canadian forces entered Haiti to “ensure order and stability.”25 These Western powers, called the Core Group, picked a new president who encouraged the deployment of these troops, giving legitimacy to what became an occupation. The Core Group also picked a new prime minister who used to work for the U.N., Gerard Latortue. Latortue met with then-French President Jacques Chirac to say that calls for French restitution to Haiti were baseless and that an amicable relationship between Haiti and France was paramount.

There were growing riots over the coup and the new government. In response, UN forces attacked poor neighborhoods, like the notable Cité Soleil, killing hundreds and committing many human rights abuses. There was outcry and uproar among the people. The U.N. justified their actions as necessary. The pro-America puppet government under Gerard Latortue pushed back the presidential election four times but was not able to quell the frustrations of Haitian citizens. In 2006, the masses elected René Préval, an associate in Aristide’s administration, in protest. He was the first head of state in Haiti’s history to serve a full, uninterrupted five-year term and peacefully transfer power.26

2010 EARTHQUAKE AND AFTERMATH

On January 10, 2010, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck Haiti not far from Port-au-Prince. The event was devastating to the country’s infrastructure and its cost to human life was staggering. The earthquake destroyed about 80-90% of the buildings at its epicenter. It brought about critical infrastructure issues. Schools, hospitals, and government buildings such as the President’s Palace and the Parliament building collapsed. The palace still has yet to be rebuilt all these years later.27 Over a million people were left homeless after the quake. For reference, Haiti’s population was 9.6 million during the disaster. According to the Government of Haiti, 300,000 people were killed as a result.28 Previous earthquakes in the years before 2010 had already weakened the country. Haitians had suffered the impact of four hurricanes and tropical storms in two months in 2008, making them especially vulnerable to the catastrophe that unfolded after January 10th, 2010.29 The quake was responsible for $7.19 Billions of dollars in damages.30

According to the US Geological Survey, there was little oversight in ensuring that buildings in Haiti were up to code. The government also lacked an emergency preparedness plan for earthquakes.31 Those left homeless were displaced, living in camps or temporary shelters set up by international non-governmental organizations—such as the International Red Cross—where tens of thousands remain to this day with no running water, electricity, or security. NGOs led the resettlement effort, filling the vacuum of leadership left by the Haitian government, who were forced to work in various temporary settings after the collapse of the Parliament building.

The United Nations and World Bank led the humanitarian relief effort. Donors such as the EU, IMF, and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) gave Haiti billions of dollars of aid for reconstruction. Despite this, it is unclear where the majority of these funds have gone or for what purposes they have been used. Much of the humanitarian aid the country received following the earthquake is unaccounted for.32 Given Haiti’s long-standing problems with corruption and malfeasance from the government, it is no surprise that many leaders embezzled large sums of this money for themselves at the expense of their constituents. Unfortunately, the government has yet to deliver on promises to improve housing, infrastructure, or earthquake preparedness.

Reginald Louissaint Jr., Haitians in Port-au-Prince warn against a return of dictatorship with Jovenl Moïse and denounce a recent surge in kidnappings, March 3, 2021, photograph, AFP/Getty Images, Port-au-Prince, Haiti, https://www.cfr.org/article/haiti's-protests-images-reflect-latest-power-struggle.

CURRENT COLLAPSE AND RESPONSE

In recent years, Haiti has been enduring security issues and a precarious political situation. One of the country’s recent leaders, Jovenel Moïse, came into power in 2017 amid allegations that his election was fraudulent. He strengthened the military and pushed economic policy to the benefit of banks while conditions degraded in Haiti and inflation rose. A fuel crisis started in 2018 because much of Haiti’s oil came from Venezuela, which halted the supply during their presidential crisis. Several officials in Moïse’s government were credibly accused of misappropriating foreign aid money. Moise was also charged with embezzling funds. Scores of Haitians protested against the administration’s handling of the economy, rising fuel prices, and corruption within his ranks.33 In response, Moise equipped paramilitary criminal gangs to suppress dissent and protests against his presidency. Moïse became increasingly unpopular since he began to rule by decree and attempted to change the Haitian constitution to give himself immunity from prosecution.

During the last year of his presidential term, controversy arose over when his term would officially conclude. The Haitian judiciary asserted that Moïse’s term was due to end in Feb 2021, five years after his controversial 2016 election. Moïse, however, stated that his presidency was supposed to end in Feb 2022, five years from when he officially assumed power.34 Feeling that he was being driven out prematurely and trying to delay a new election, Moïse tightened his grip on power, heightening turmoil in the country. Moise’s government fell apart as he had no supporters around him. On July 7th, 2021, Moïse was assassinated. It was a U.S. security firm that recruited the mercenaries, many of whom were American military trained, that killed Moïse.35 Several transitional and interim leaders have assumed power in the wake of his killing. His death has left a vacuum of political leadership in a state with no defined order of succession.

Gangs have since become legitimized authorities and hold control over the population, partly through campaigns of terror where they kidnap ordinary civilians for ransom. Gangs control substantial territory across Haiti and are the true authority in the country in the absence of government. The security situation has deteriorated as the future of the country is imperiled by gang warfare. For these reasons, the number of undocumented Haitian migrants attempting to enter the U.S. has been rising. To counter this, the Obama administration granted temporary protected status (TPS) to Haitian refugees who wished to immigrate to the U.S. in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake. The TPS designation allows nationals from specific countries facing extraordinarily dire circumstances to live and work here for a period of time.36

Immigration is an issue central to U.S.-Haiti relations. Recent presidential administrations have taken different approaches to address the fallout from Haiti’s instability. The Trump administration cut humanitarian aid to the country and sought to halt the granting of TPS to more Haitians. Trump also refused to renew protection for refugees who had already received TPS, leading thousands to be deported. Legal battles followed challenging his administration until Haiti’s TPS designation was restored. In March 2020, the Trump White House also invoked Title 42, a public health order that blocked migrants from being allowed entry to the U.S. for fear of facilitating the spread of communicable diseases. Title 42 was used to expel migrants, denying them their right to seek asylum. Though the Biden administration promised to do everything in its power to help the fragile Haiti, they also allowed the deportations to continue until 2023.37

CONCLUSION

The migration of Haitian refugees to the U.S. has become a politically charged issue as of late, as a significant number of Haitian citizens are desperate to leave the country. The social, economic, and political conditions in Haiti are unraveling. Gangs now control 60% of the capital and are fighting for control of Port-au-Prince, threatening the rule of law.38 Unfortunately, there is little the government can do to curb their growing influence. The UN is now taking the reins over affairs in Haiti again, planning to deploy a thousand UN officers to bring about order even though Haitians strongly oppose and condemn continued Western interference in their country. Another election is slated to take place in August 2025 to fill the vacuum of the presidency that has remained since Moise’s 2021 assassination.39

Any stable future for Haiti is dependent on the will of its people being done, as their autonomy, self-empowerment, and self-determination has been undercut at every single instance by Western powers. Life for the everyday Haitian is challenging. Even the basics like securing food, water, and gas are incredibly difficult for millions. Little is certain about the country’s future. The only constants in recent decades have been change, flux, and chaos. Even so, reflecting on Haiti’s difficult past is prudent as misconceptions abound about its people and their hardships. This article aims to draw attention to the background of Haiti’s troubles and provide historical context to the country’s current dilemmas. No good will come to Haitians unless more people learn about their circumstances. This tiny nation has an unparalleled story of resilience that is not widely known and must be shared. As such, we must take it upon ourselves to do our due diligence by educating ourselves and giving Haiti the dignity it deserves. We cannot let the suffering of the Haitian people be for naught.

Bibliography

Banking on Solidarity. “Citibank and Haitians: A Violent History.” Accessed on January 05, 2025. https://www.bankingonsolidarity.org/citibank-and-haitians-a-violent-history/.

Charles, Jacqueline, and Jose Antonio Iglesias. “Ten Years after Haiti’s Earthquake: A Decade of Aftershocks and Unkept Promises.” Pulitzer Center, January 20, 2020. https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/ten-years-after-haitis-earthquake-decade-aftershocks-and-unkept-promises.

Cheatham, Amelia, and Sabine Baumgartner. “Haiti’s Protests: Images Reflect Latest Power Struggle.” Council on Foreign Relations, March 3, 2021. https://www.cfr.org/article/haitis-protests-images-reflect-latest-power-struggle.

DesRoches, Reginald . “Overview of the 2010 Haiti Earthquake.” Earthquake Spectra, 27, no. S1 (October 1, 2011): 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1193/1.3630129.

Gamio, Lazaro, Constant Méheut, Catherine Porter, Selam Gebrekidan, Allison McCann, and Matt Apuzzo. “Haiti’s Lost Billions.” The New York Times, May 20, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/05/20/world/americas/enslaved-haiti-debt-timeline.html.

“How the U.S. And France Made Haiti Poor.” Posted July 21, 2021, by Al Jazeera. YouTube, 6 min., 42 sec. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P2kbliq8AUc.

“How the World Destroyed Haiti.” Posted April 30, 2023, by Scholar Casual. YouTube, 30 min., 17 sec. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KpOtkVRnH54.

Louissant, Reginald Jr. Haitians in Port-au-Prince warn against a return of dictatorship with Jovenl Moïse and denounce a recent surge in kidnappings. March 3, 2021, photograph, AFP/Getty Images, Port-au-Prince, Haiti. https://www.cfr.org/article/haiti's-protests-images-reflect-latest-power-struggle.

Nickelsberg, Robert. Close-up of Haitian president-elect Jean-Bertrand Aristide as he holds a press conference after winning the election, Port-au-Prince, Haiti. November 27, 2000, photograph, Getty Images, Port-au-Prince, Haiti. https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/close-up-of-haitian-president-elect-jean-bertrand-aristide-news-photo/1490204865.

Retamal, Hector. Polling center employees in Port-au-Prince tally votes November 21, 2016 one day after the Haitian presidential and legislative elections. November 22, 2016, photograph, AFP, Port-au-Prince, Haiti. https://www.france24.com/en/20161122-haiti-rival-parties-claim-victory-presidential-election.

Roy, Diana, and Rocio Cara Labrador. “Haiti’s Troubled Path to Development.” Council on Foreign Relations, June 25, 2024. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/haitis-troubled-path-development#chapter-title-0-8.

Sutherland, Claudia. “Haitian Revolution (1791-1804).” BlackPast, July 16, 2007. https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/haitian-revolution-1791-1804/.

The University of Kansas Institute of Haitian Studies. “HAITI: A Brief History of a Complex Nation.” Institute for Haitian Studies, accessed on January 05, 2025. https://haitianstudies.ku.edu/haiti-brief-history-complex-nation.

Tremblay, Benjamin. “Le pillage du peuple haïtien, raconté | Documentaire.” Posted January 1, 2023, by 7 jours sur Terre. YouTube, 52 min., 54 sec. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VpOzIQPDa_w.

Diana Roy and Rocio Cara Labrador, “Haiti’s Troubled Path to Development,” Council on Foreign Relations, June 25, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/haitis-troubled-path-development#chapter-title-0-8.

Benjamin, Tremblay, “Le pillage du peuple haïtien, raconté | Documentaire,” posted January 1, 2023, by 7 jours sur Terre, YouTube, 52 min., 54 sec, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VpOzIQPDa_w.

Claudia Sutherland, “Haitian Revolution (1791-1804),” BlackPast, July 16, 2007. https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/haitian-revolution-1791-1804/.

Ibid.

The University of Kansas Institute of Haitian Studies, “HAITI: A Brief History of a Complex Nation,” Institute for Haitian Studies, accessed on January 05, 2025, https://haitianstudies.ku.edu/haiti-brief-history-complex-nation.

“How the World Destroyed Haiti,” posted April 30, 2023, by Scholar Casual, YouTube, 30 min., 17 sec, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KpOtkVRnH54.

Lazaro Gamio et. al, “Haiti’s Lost Billions,” The New York Times, May, 20, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/05/20/world/americas/enslaved-haiti-debt-timeline.html.

Ibid.

“How the U.S. And France Made Haiti Poor,” posted July 21, 2021, by Al Jazeera, YouTube, 6 min., 42 sec, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P2kbliq8AUc.

Diana Roy and Rocio Cara Labrador, “Haiti’s Troubled Path to Development,” Council on Foreign Relations, June 25, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/haitis-troubled-path-development#chapter-title-0-8.

Roy and Labrador, “Haiti’s Troubled Path to Development.”

Tremblay, “Le pillage du peuple haïtien, raconté | Documentaire.”

“Citibank and Haitians: A Violent History,” Banking on Solidarity, accessed on January 05, 2025, https://www.bankingonsolidarity.org/citibank-and-haitians-a-violent-history/.

Tremblay, “Le pillage du peuple haïtien, raconté | Documentaire.”

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

“How the U.S. and France Made Haiti Poor.”

Tremblay, “Le pillage du peuple haïtien, raconté | Documentaire.”

Ibid.

Roy and Labrador, “Haiti’s Troubled Path to Development.”

Tremblay, “Le pillage du peuple haïtien, raconté | Documentaire.”

Ibid.

Reginald, DesRoches, “Overview of the 2010 Haiti Earthquake.” Earthquake Spectra, 27, no. S1 (October 1, 2011): 2. https://doi.org/10.1193/1.3630129.

Reginald, DesRoches, “Overview of the 2010 Haiti Earthquake,” 1.

Ibid.

Jacqueline Charles and José Antonio Iglesias, “Ten Years After Haiti’s Earthquake: A Decade of Aftershocks and Unkept Promises,” Pulitzer Center, January 8, 2020, https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/ten-years-after-haitis-earthquake-decade-aftershocks-and-unkept-promises.

Reginald, DesRoches, “Overview of the 2010 Haiti Earthquake,” 3.

Charles and Iglesias, “Ten Years After Haiti’s Earthquake: A Decade of Aftershocks and Unkept Promises.”

Roy and Labrador, “Haiti’s Troubled Path to Development.”

“How the U.S. and France Made Haiti Poor.”

Roy and Labrador, “Haiti’s Troubled Path to Development.”

Ibid.

Ibid.

Tremblay, “Le pillage du peuple haïtien, raconté | Documentaire.”

Roy and Labrador, “Haiti’s Troubled Path to Development.”